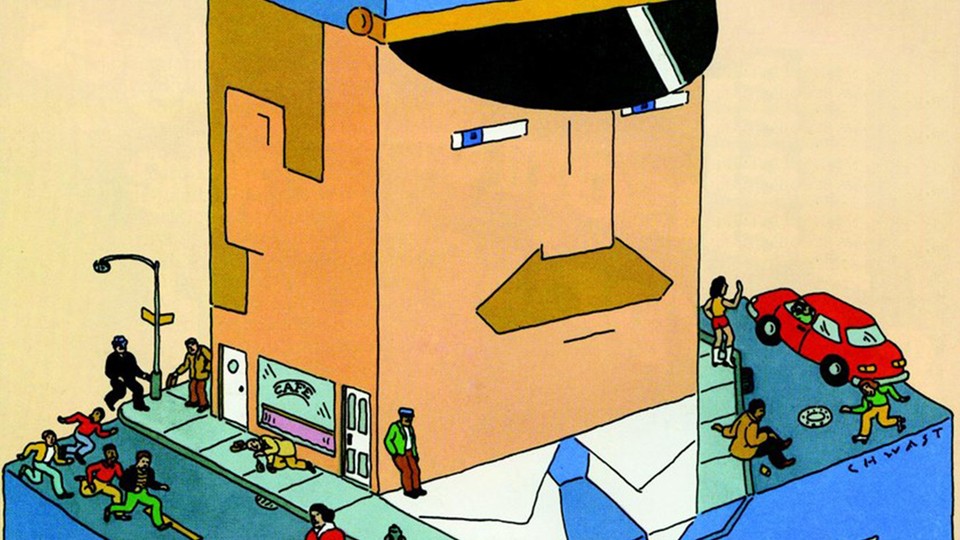

The police and neighborhood safety

Editor’s Note: We’ve gathered dozens of the most important pieces from our archives on race and racism in America. Find the collection here.

In the mid-1970s The State of New Jersey announced a «Safe and Clean Neighborhoods Program,» designed to improve the quality of community life in twenty-eight cities. As part of that program, the state provided money to help cities take police officers out of their patrol cars and assign them to walking beats. The governor and other state officials were enthusiastic about using foot patrol as a way of cutting crime, but many police chiefs were skeptical. Foot patrol, in their eyes, had been pretty much discredited. It reduced the mobility of the police, who thus had difficulty responding to citizen calls for service, and it weakened headquarters control over patrol officers.

Many police officers also disliked foot patrol, but for different reasons: it was hard work, it kept them outside on cold, rainy nights, and it reduced their chances for making a «good pinch.» In some departments, assigning officers to foot patrol had been used as a form of punishment. And academic experts on policing doubted that foot patrol would have any impact on crime rates; it was, in the opinion of most, little more than a sop to public opinion. But since the state was paying for it, the local authorities were willing to go along.

Five years after the program started, the Police Foundation, in Washington, D.C., published an evaluation of the foot-patrol project. Based on its analysis of a carefully controlled experiment carried out chiefly in Newark, the foundation concluded, to the surprise of hardly anyone, that foot patrol had not reduced crime rates. But residents of the foot patrolled neighborhoods seemed to feel more secure than persons in other areas, tended to believe that crime had been reduced, and seemed to take fewer steps to protect themselves from crime (staying at home with the doors locked, for example). Moreover, citizens in the foot-patrol areas had a more favorable opinion of the police than did those living elsewhere. And officers walking beats had higher morale, greater job satisfaction, and a more favorable attitude toward citizens in their neighborhoods than did officers assigned to patrol cars.

These findings may be taken as evidence that the skeptics were right- foot patrol has no effect on crime; it merely fools the citizens into thinking that they are safer. But in our view, and in the view of the authors of the Police Foundation study (of whom Kelling was one), the citizens of Newark were not fooled at all. They knew what the foot-patrol officers were doing, they knew it was different from what motorized officers do, and they knew that having officers walk beats did in fact make their neighborhoods safer.

But how can a neighborhood be «safer» when the crime rate has not gone down—in fact, may have gone up? Finding the answer requires first that we understand what most often frightens people in public places. Many citizens, of course, are primarily frightened by crime, especially crime involving a sudden, violent attack by a stranger. This risk is very real, in Newark as in many large cities. But we tend to overlook another source of fear—the fear of being bothered by disorderly people. Not violent people, nor, necessarily, criminals, but disreputable or obstreperous or unpredictable people: panhandlers, drunks, addicts, rowdy teenagers, prostitutes, loiterers, the mentally disturbed.

What foot-patrol officers did was to elevate, to the extent they could, the level of public order in these neighborhoods. Though the neighborhoods were predominantly black and the foot patrolmen were mostly white, this «order-maintenance» function of the police was performed to the general satisfaction of both parties.

One of us (Kelling) spent many hours walking with Newark foot-patrol officers to see how they defined «order» and what they did to maintain it. One beat was typical: a busy but dilapidated area in the heart of Newark, with many abandoned buildings, marginal shops (several of which prominently displayed knives and straight-edged razors in their windows), one large department store, and, most important, a train station and several major bus stops. Though the area was run-down, its streets were filled with people, because it was a major transportation center. The good order of this area was important not only to those who lived and worked there but also to many others, who had to move through it on their way home, to supermarkets, or to factories.

The people on the street were primarily black; the officer who walked the street was white. The people were made up of «regulars» and «strangers.» Regulars included both «decent folk» and some drunks and derelicts who were always there but who «knew their place.» Strangers were, well, strangers, and viewed suspiciously, sometimes apprehensively. The officer—call him Kelly—knew who the regulars were, and they knew him. As he saw his job, he was to keep an eye on strangers, and make certain that the disreputable regulars observed some informal but widely understood rules. Drunks and addicts could sit on the stoops, but could not lie down. People could drink on side streets, but not at the main intersection. Bottles had to be in paper bags. Talking to, bothering, or begging from people waiting at the bus stop was strictly forbidden. If a dispute erupted between a businessman and a customer, the businessman was assumed to be right, especially if the customer was a stranger. If a stranger loitered, Kelly would ask him if he had any means of support and what his business was; if he gave unsatisfactory answers, he was sent on his way. Persons who broke the informal rules, especially those who bothered people waiting at bus stops, were arrested for vagrancy. Noisy teenagers were told to keep quiet.

These rules were defined and enforced in collaboration with the «regulars» on the street. Another neighborhood might have different rules, but these, everybody understood, were the rules for this neighborhood. If someone violated them, the regulars not only turned to Kelly for help but also ridiculed the violator. Sometimes what Kelly did could be described as «enforcing the law,» but just as often it involved taking informal or extralegal steps to help protect what the neighborhood had decided was the appropriate level of public order. Some of the things he did probably would not withstand a legal challenge.

A determined skeptic might acknowledge that a skilled foot-patrol officer can maintain order but still insist that this sort of «order» has little to do with the real sources of community fear—that is, with violent crime. To a degree, that is true. But two things must be borne in mind. First, outside observers should not assume that they know how much of the anxiety now endemic in many big-city neighborhoods stems from a fear of «real» crime and how much from a sense that the street is disorderly, a source of distasteful, worrisome encounters. The people of Newark, to judge from their behavior and their remarks to interviewers, apparently assign a high value to public order, and feel relieved and reassured when the police help them maintain that order.

Second, at the community level, disorder and crime are usually inextricably linked, in a kind of developmental sequence. Social psychologists and police officers tend to agree that if a window in a building is broken and is left unrepaired, all the rest of the windows will soon be broken. This is as true in nice neighborhoods as in rundown ones. Window-breaking does not necessarily occur on a large scale because some areas are inhabited by determined window-breakers whereas others are populated by window-lovers; rather, one unrepaired broken window is a signal that no one cares, and so breaking more windows costs nothing. (It has always been fun.)

Philip Zimbardo, a Stanford psychologist, reported in 1969 on some experiments testing the broken-window theory. He arranged to have an automobile without license plates parked with its hood up on a street in the Bronx and a comparable automobile on a street in Palo Alto, California. The car in the Bronx was attacked by «vandals» within ten minutes of its «abandonment.» The first to arrive were a family—father, mother, and young son—who removed the radiator and battery. Within twenty-four hours, virtually everything of value had been removed. Then random destruction began—windows were smashed, parts torn off, upholstery ripped. Children began to use the car as a playground. Most of the adult «vandals» were well-dressed, apparently clean-cut whites. The car in Palo Alto sat untouched for more than a week. Then Zimbardo smashed part of it with a sledgehammer. Soon, passersby were joining in. Within a few hours, the car had been turned upside down and utterly destroyed. Again, the «vandals» appeared to be primarily respectable whites.

Untended property becomes fair game for people out for fun or plunder and even for people who ordinarily would not dream of doing such things and who probably consider themselves law-abiding. Because of the nature of community life in the Bronx—its anonymity, the frequency with which cars are abandoned and things are stolen or broken, the past experience of «no one caring»—vandalism begins much more quickly than it does in staid Palo Alto, where people have come to believe that private possessions are cared for, and that mischievous behavior is costly. But vandalism can occur anywhere once communal barriers—the sense of mutual regard and the obligations of civility—are lowered by actions that seem to signal that «no one cares.»

We suggest that «untended» behavior also leads to the breakdown of community controls. A stable neighborhood of families who care for their homes, mind each other’s children, and confidently frown on unwanted intruders can change, in a few years or even a few months, to an inhospitable and frightening jungle. A piece of property is abandoned, weeds grow up, a window is smashed. Adults stop scolding rowdy children; the children, emboldened, become more rowdy. Families move out, unattached adults move in. Teenagers gather in front of the corner store. The merchant asks them to move; they refuse. Fights occur. Litter accumulates. People start drinking in front of the grocery; in time, an inebriate slumps to the sidewalk and is allowed to sleep it off. Pedestrians are approached by panhandlers.

At this point it is not inevitable that serious crime will flourish or violent attacks on strangers will occur. But many residents will think that crime, especially violent crime, is on the rise, and they will modify their behavior accordingly. They will use the streets less often, and when on the streets will stay apart from their fellows, moving with averted eyes, silent lips, and hurried steps. «Don’t get involved.» For some residents, this growing atomization will matter little, because the neighborhood is not their «home» but «the place where they live.» Their interests are elsewhere; they are cosmopolitans. But it will matter greatly to other people, whose lives derive meaning and satisfaction from local attachments rather than worldly involvement; for them, the neighborhood will cease to exist except for a few reliable friends whom they arrange to meet.

Such an area is vulnerable to criminal invasion. Though it is not inevitable, it is more likely that here, rather than in places where people are confident they can regulate public behavior by informal controls, drugs will change hands, prostitutes will solicit, and cars will be stripped. That the drunks will be robbed by boys who do it as a lark, and the prostitutes’ customers will be robbed by men who do it purposefully and perhaps violently. That muggings will occur.

Among those who often find it difficult to move away from this are the elderly. Surveys of citizens suggest that the elderly are much less likely to be the victims of crime than younger persons, and some have inferred from this that the well-known fear of crime voiced by the elderly is an exaggeration: perhaps we ought not to design special programs to protect older persons; perhaps we should even try to talk them out of their mistaken fears. This argument misses the point. The prospect of a confrontation with an obstreperous teenager or a drunken panhandler can be as fear-inducing for defenseless persons as the prospect of meeting an actual robber; indeed, to a defenseless person, the two kinds of confrontation are often indistinguishable. Moreover, the lower rate at which the elderly are victimized is a measure of the steps they have already taken—chiefly, staying behind locked doors—to minimize the risks they face. Young men are more frequently attacked than older women, not because they are easier or more lucrative targets but because they are on the streets more.

Nor is the connection between disorderliness and fear made only by the elderly. Susan Estrich, of the Harvard Law School, has recently gathered together a number of surveys on the sources of public fear. One, done in Portland, Oregon, indicated that three fourths of the adults interviewed cross to the other side of a street when they see a gang of teenagers; another survey, in Baltimore, discovered that nearly half would cross the street to avoid even a single strange youth. When an interviewer asked people in a housing project where the most dangerous spot was, they mentioned a place where young persons gathered to drink and play music, despite the fact that not a single crime had occurred there. In Boston public housing projects, the greatest fear was expressed by persons living in the buildings where disorderliness and incivility, not crime, were the greatest. Knowing this helps one understand the significance of such otherwise harmless displays as subway graffiti. As Nathan Glazer has written, the proliferation of graffiti, even when not obscene, confronts the subway rider with the inescapable knowledge that the environment he must endure for an hour or more a day is uncontrolled and uncontrollable, and that anyone can invade it to do whatever damage and mischief the mind suggests.»

In response to fear people avoid one another, weakening controls. Sometimes they call the police. Patrol cars arrive, an occasional arrest occurs but crime continues and disorder is not abated. Citizens complain to the police chief, but he explains that his department is low on personnel and that the courts do not punish petty or first-time offenders. To the residents, the police who arrive in squad cars are either ineffective or uncaring: to the police, the residents are animals who deserve each other. The citizens may soon stop calling the police, because «they can’t do anything.»

The process we call urban decay has occurred for centuries in every city. But what is happening today is different in at least two important respects. First, in the period before, say, World War II, city dwellers- because of money costs, transportation difficulties, familial and church connections—could rarely move away from neighborhood problems. When movement did occur, it tended to be along public-transit routes. Now mobility has become exceptionally easy for all but the poorest or those who are blocked by racial prejudice. Earlier crime waves had a kind of built-in self-correcting mechanism: the determination of a neighborhood or community to reassert control over its turf. Areas in Chicago, New York, and Boston would experience crime and gang wars, and then normalcy would return, as the families for whom no alternative residences were possible reclaimed their authority over the streets.

Second, the police in this earlier period assisted in that reassertion of authority by acting, sometimes violently, on behalf of the community. Young toughs were roughed up, people were arrested «on suspicion» or for vagrancy, and prostitutes and petty thieves were routed. «Rights» were something enjoyed by decent folk, and perhaps also by the serious professional criminal, who avoided violence and could afford a lawyer.

This pattern of policing was not an aberration or the result of occasional excess. From the earliest days of the nation, the police function was seen primarily as that of a night watchman: to maintain order against the chief threats to order—fire, wild animals, and disreputable behavior. Solving crimes was viewed not as a police responsibility but as a private one. In the March, 1969, Atlantic, one of us (Wilson) wrote a brief account of how the police role had slowly changed from maintaining order to fighting crimes. The change began with the creation of private detectives (often ex-criminals), who worked on a contingency-fee basis for individuals who had suffered losses. In time, the detectives were absorbed in municipal agencies and paid a regular salary simultaneously, the responsibility for prosecuting thieves was shifted from the aggrieved private citizen to the professional prosecutor. This process was not complete in most places until the twentieth century.

In the l960s, when urban riots were a major problem, social scientists began to explore carefully the order maintenance function of the police, and to suggest ways of improving it—not to make streets safer (its original function) but to reduce the incidence of mass violence. Order maintenance became, to a degree, coterminous with «community relations.» But, as the crime wave that began in the early l960s continued without abatement throughout the decade and into the 1970s, attention shifted to the role of the police as crime-fighters. Studies of police behavior ceased, by and large, to be accounts of the order-maintenance function and became, instead, efforts to propose and test ways whereby the police could solve more crimes, make more arrests, and gather better evidence. If these things could be done, social scientists assumed, citizens would be less fearful.

A great deal was accomplished during this transition, as both police chiefs and outside experts emphasized the crime-fighting function in their plans, in the allocation of resources, and in deployment of personnel. The police may well have become better crime-fighters as a result. And doubtless they remained aware of their responsibility for order. But the link between order-maintenance and crime-prevention, so obvious to earlier generations, was forgotten.

Recommended Reading

That link is similar to the process whereby one broken window becomes many. The citizen who fears the ill-smelling drunk, the rowdy teenager, or the importuning beggar is not merely expressing his distaste for unseemly behavior; he is also giving voice to a bit of folk wisdom that happens to be a correct generalization—namely, that serious street crime flourishes in areas in which disorderly behavior goes unchecked. The unchecked panhandler is, in effect, the first broken window. Muggers and robbers, whether opportunistic or professional, believe they reduce their chances of being caught or even identified if they operate on streets where potential victims are already intimidated by prevailing conditions. If the neighborhood cannot keep a bothersome panhandler from annoying passersby, the thief may reason, it is even less likely to call the police to identify a potential mugger or to interfere if the mugging actually takes place.

Some police administrators concede that this process occurs, but argue that motorized-patrol officers can deal with it as effectively as foot patrol officers. We are not so sure. In theory, an officer in a squad car can observe as much as an officer on foot; in theory, the former can talk to as many people as the latter. But the reality of police-citizen encounters is powerfully altered by the automobile. An officer on foot cannot separate himself from the street people; if he is approached, only his uniform and his personality can help him manage whatever is about to happen. And he can never be certain what that will be—a request for directions, a plea for help, an angry denunciation, a teasing remark, a confused babble, a threatening gesture.

In a car, an officer is more likely to deal with street people by rolling down the window and looking at them. The door and the window exclude the approaching citizen; they are a barrier. Some officers take advantage of this barrier, perhaps unconsciously, by acting differently if in the car than they would on foot. We have seen this countless times. The police car pulls up to a corner where teenagers are gathered. The window is rolled down. The officer stares at the youths. They stare back. The officer says to one, «C’mere.» He saunters over, conveying to his friends by his elaborately casual style the idea that he is not intimidated by authority. What’s your name?» «Chuck.» «Chuck who?» «Chuck Jones.» «What’ya doing, Chuck?» «Nothin’.» «Got a P.O. [parole officer]?» «Nah.» «Sure?» «Yeah.» «Stay out of trouble, Chuckie.» Meanwhile, the other boys laugh and exchange comments among themselves, probably at the officer’s expense. The officer stares harder. He cannot be certain what is being said, nor can he join in and, by displaying his own skill at street banter, prove that he cannot be «put down.» In the process, the officer has learned almost nothing, and the boys have decided the officer is an alien force who can safely be disregarded, even mocked.

Our experience is that most citizens like to talk to a police officer. Such exchanges give them a sense of importance, provide them with the basis for gossip, and allow them to explain to the authorities what is worrying them (whereby they gain a modest but significant sense of having «done something» about the problem). You approach a person on foot more easily, and talk to him more readily, than you do a person in a car. Moreover, you can more easily retain some anonymity if you draw an officer aside for a private chat. Suppose you want to pass on a tip about who is stealing handbags, or who offered to sell you a stolen TV. In the inner city, the culprit, in all likelihood, lives nearby. To walk up to a marked patrol car and lean in the window is to convey a visible signal that you are a «fink.»

The essence of the police role in maintaining order is to reinforce the informal control mechanisms of the community itself. The police cannot, without committing extraordinary resources, provide a substitute for that informal control. On the other hand, to reinforce those natural forces the police must accommodate them. And therein lies the problem.

Should police activity on the street be shaped, in important ways, by the standards of the neighborhood rather than by the rules of the state? Over the past two decades, the shift of police from order-maintenance to law enforcement has brought them increasingly under the influence of legal restrictions, provoked by media complaints and enforced by court decisions and departmental orders. As a consequence, the order maintenance functions of the police are now governed by rules developed to control police relations with suspected criminals. This is, we think, an entirely new development. For centuries, the role of the police as watchmen was judged primarily not in terms of its compliance with appropriate procedures but rather in terms of its attaining a desired objective. The objective was order, an inherently ambiguous term but a condition that people in a given community recognized when they saw it. The means were the same as those the community itself would employ, if its members were sufficiently determined, courageous, and authoritative. Detecting and apprehending criminals, by contrast, was a means to an end, not an end in itself; a judicial determination of guilt or innocence was the hoped-for result of the law-enforcement mode. From the first, the police were expected to follow rules defining that process, though states differed in how stringent the rules should be. The criminal-apprehension process was always understood to involve individual rights, the violation of which was unacceptable because it meant that the violating officer would be acting as a judge and jury—and that was not his job. Guilt or innocence was to be determined by universal standards under special procedures.

Ordinarily, no judge or jury ever sees the persons caught up in a dispute over the appropriate level of neighborhood order. That is true not only because most cases are handled informally on the street but also because no universal standards are available to settle arguments over disorder, and thus a judge may not be any wiser or more effective than a police officer. Until quite recently in many states, and even today in some places, the police made arrests on such charges as «suspicious person» or «vagrancy» or «public drunkenness»—charges with scarcely any legal meaning. These charges exist not because society wants judges to punish vagrants or drunks but because it wants an officer to have the legal tools to remove undesirable persons from a neighborhood when informal efforts to preserve order in the streets have failed.

Once we begin to think of all aspects of police work as involving the application of universal rules under special procedures, we inevitably ask what constitutes an «undesirable person» and why we should «criminalize» vagrancy or drunkenness. A strong and commendable desire to see that people are treated fairly makes us worry about allowing the police to rout persons who are undesirable by some vague or parochial standard. A growing and not-so-commendable utilitarianism leads us to doubt that any behavior that does not «hurt» another person should be made illegal. And thus many of us who watch over the police are reluctant to allow them to perform, in the only way they can, a function that every neighborhood desperately wants them to perform.

This wish to «decriminalize» disreputable behavior that «harms no one»- and thus remove the ultimate sanction the police can employ to maintain neighborhood order—is, we think, a mistake. Arresting a single drunk or a single vagrant who has harmed no identifiable person seems unjust, and in a sense it is. But failing to do anything about a score of drunks or a hundred vagrants may destroy an entire community. A particular rule that seems to make sense in the individual case makes no sense when it is made a universal rule and applied to all cases. It makes no sense because it fails to take into account the connection between one broken window left untended and a thousand broken windows. Of course, agencies other than the police could attend to the problems posed by drunks or the mentally ill, but in most communities especially where the «deinstitutionalization» movement has been strong—they do not.

The concern about equity is more serious. We might agree that certain behavior makes one person more undesirable than another but how do we ensure that age or skin color or national origin or harmless mannerisms will not also become the basis for distinguishing the undesirable from the desirable? How do we ensure, in short, that the police do not become the agents of neighborhood bigotry?

We can offer no wholly satisfactory answer to this important question. We are not confident that there is a satisfactory answer except to hope that by their selection, training, and supervision, the police will be inculcated with a clear sense of the outer limit of their discretionary authority. That limit, roughly, is this—the police exist to help regulate behavior, not to maintain the racial or ethnic purity of a neighborhood.

Consider the case of the Robert Taylor Homes in Chicago, one of the largest public-housing projects in the country. It is home for nearly 20,000 people, all black, and extends over ninety-two acres along South State Street. It was named after a distinguished black who had been, during the 1940s, chairman of the Chicago Housing Authority. Not long after it opened, in 1962, relations between project residents and the police deteriorated badly. The citizens felt that the police were insensitive or brutal; the police, in turn, complained of unprovoked attacks on them. Some Chicago officers tell of times when they were afraid to enter the Homes. Crime rates soared.

Today, the atmosphere has changed. Police-citizen relations have improved—apparently, both sides learned something from the earlier experience. Recently, a boy stole a purse and ran off. Several young persons who saw the theft voluntarily passed along to the police information on the identity and residence of the thief, and they did this publicly, with friends and neighbors looking on. But problems persist, chief among them the presence of youth gangs that terrorize residents and recruit members in the project. The people expect the police to «do something» about this, and the police are determined to do just that.

But do what? Though the police can obviously make arrests whenever a gang member breaks the law, a gang can form, recruit, and congregate without breaking the law. And only a tiny fraction of gang-related crimes can be solved by an arrest; thus, if an arrest is the only recourse for the police, the residents’ fears will go unassuaged. The police will soon feel helpless, and the residents will again believe that the police «do nothing.» What the police in fact do is to chase known gang members out of the project. In the words of one officer, «We kick ass.» Project residents both know and approve of this. The tacit police-citizen alliance in the project is reinforced by the police view that the cops and the gangs are the two rival sources of power in the area, and that the gangs are not going to win.

None of this is easily reconciled with any conception of due process or fair treatment. Since both residents and gang members are black, race is not a factor. But it could be. Suppose a white project confronted a black gang, or vice versa. We would be apprehensive about the police taking sides. But the substantive problem remains the same: how can the police strengthen the informal social-control mechanisms of natural communities in order to minimize fear in public places? Law enforcement, per se, is no answer: a gang can weaken or destroy a community by standing about in a menacing fashion and speaking rudely to passersby without breaking the law.

We have difficulty thinking about such matters, not simply because the ethical and legal issues are so complex but because we have become accustomed to thinking of the law in essentially individualistic terms. The law defines my rights, punishes his behavior and is applied by that officer because of this harm. We assume, in thinking this way, that what is good for the individual will be good for the community and what doesn’t matter when it happens to one person won’t matter if it happens to many. Ordinarily, those are plausible assumptions. But in cases where behavior that is tolerable to one person is intolerable to many others, the reactions of the others—fear, withdrawal, flight—may ultimately make matters worse for everyone, including the individual who first professed his indifference.

It may be their greater sensitivity to communal as opposed to individual needs that helps explain why the residents of small communities are more satisfied with their police than are the residents of similar neighborhoods in big cities. Elinor Ostrom and her co-workers at Indiana University compared the perception of police services in two poor, all-black Illinois towns—Phoenix and East Chicago Heights with those of three comparable all-black neighborhoods in Chicago. The level of criminal victimization and the quality of police-community relations appeared to be about the same in the towns and the Chicago neighborhoods. But the citizens living in their own villages were much more likely than those living in the Chicago neighborhoods to say that they do not stay at home for fear of crime, to agree that the local police have «the right to take any action necessary» to deal with problems, and to agree that the police «look out for the needs of the average citizen.» It is possible that the residents and the police of the small towns saw themselves as engaged in a collaborative effort to maintain a certain standard of communal life, whereas those of the big city felt themselves to be simply requesting and supplying particular services on an individual basis.

If this is true, how should a wise police chief deploy his meager forces? The first answer is that nobody knows for certain, and the most prudent course of action would be to try further variations on the Newark experiment, to see more precisely what works in what kinds of neighborhoods. The second answer is also a hedge—many aspects of order maintenance in neighborhoods can probably best be handled in ways that involve the police minimally if at all. A busy bustling shopping center and a quiet, well-tended suburb may need almost no visible police presence. In both cases, the ratio of respectable to disreputable people is ordinarily so high as to make informal social control effective.

Even in areas that are in jeopardy from disorderly elements, citizen action without substantial police involvement may be sufficient. Meetings between teenagers who like to hang out on a particular corner and adults who want to use that corner might well lead to an amicable agreement on a set of rules about how many people can be allowed to congregate, where, and when.

Where no understanding is possible—or if possible, not observed—citizen patrols may be a sufficient response. There are two traditions of communal involvement in maintaining order: One, that of the «community watchmen,» is as old as the first settlement of the New World. Until well into the nineteenth century, volunteer watchmen, not policemen, patrolled their communities to keep order. They did so, by and large, without taking the law into their own hands—without, that is, punishing persons or using force. Their presence deterred disorder or alerted the community to disorder that could not be deterred. There are hundreds of such efforts today in communities all across the nation. Perhaps the best known is that of the Guardian Angels, a group of unarmed young persons in distinctive berets and T-shirts, who first came to public attention when they began patrolling the New York City subways but who claim now to have chapters in more than thirty American cities. Unfortunately, we have little information about the effect of these groups on crime. It is possible, however, that whatever their effect on crime, citizens find their presence reassuring, and that they thus contribute to maintaining a sense of order and civility.

The second tradition is that of the «vigilante.» Rarely a feature of the settled communities of the East, it was primarily to be found in those frontier towns that grew up in advance of the reach of government. More than 350 vigilante groups are known to have existed; their distinctive feature was that their members did take the law into their own hands, by acting as judge, jury, and often executioner as well as policeman. Today, the vigilante movement is conspicuous by its rarity, despite the great fear expressed by citizens that the older cities are becoming «urban frontiers.» But some community-watchmen groups have skirted the line, and others may cross it in the future. An ambiguous case, reported in The Wall Street Journal involved a citizens’ patrol in the Silver Lake area of Belleville, New Jersey. A leader told the reporter, «We look for outsiders.» If a few teenagers from outside the neighborhood enter it, «we ask them their business,» he said. «If they say they’re going down the street to see Mrs. Jones, fine, we let them pass. But then we follow them down the block to make sure they’re really going to see Mrs. Jones.»

Though citizens can do a great deal, the police are plainly the key to order maintenance. For one thing, many communities, such as the Robert Taylor Homes, cannot do the job by themselves. For another, no citizen in a neighborhood, even an organized one, is likely to feel the sense of responsibility that wearing a badge confers. Psychologists have done many studies on why people fail to go to the aid of persons being attacked or seeking help, and they have learned that the cause is not «apathy» or «selfishness» but the absence of some plausible grounds for feeling that one must personally accept responsibility. Ironically, avoiding responsibility is easier when a lot of people are standing about. On streets and in public places, where order is so important, many people are likely to be «around,» a fact that reduces the chance of any one person acting as the agent of the community. The police officer’s uniform singles him out as a person who must accept responsibility if asked. In addition, officers, more easily than their fellow citizens, can be expected to distinguish between what is necessary to protect the safety of the street and what merely protects its ethnic purity.

But the police forces of America are losing, not gaining, members. Some cities have suffered substantial cuts in the number of officers available for duty. These cuts are not likely to be reversed in the near future. Therefore, each department must assign its existing officers with great care. Some neighborhoods are so demoralized and crime-ridden as to make foot patrol useless; the best the police can do with limited resources is respond to the enormous number of calls for service. Other neighborhoods are so stable and serene as to make foot patrol unnecessary. The key is to identify neighborhoods at the tipping point—where the public order is deteriorating but not unreclaimable, where the streets are used frequently but by apprehensive people, where a window is likely to be broken at any time, and must quickly be fixed if all are not to be shattered.

Most police departments do not have ways of systematically identifying such areas and assigning officers to them. Officers are assigned on the basis of crime rates (meaning that marginally threatened areas are often stripped so that police can investigate crimes in areas where the situation is hopeless) or on the basis of calls for service (despite the fact that most citizens do not call the police when they are merely frightened or annoyed). To allocate patrol wisely, the department must look at the neighborhoods and decide, from first-hand evidence, where an additional officer will make the greatest difference in promoting a sense of safety.

One way to stretch limited police resources is being tried in some public housing projects. Tenant organizations hire off-duty police officers for patrol work in their buildings. The costs are not high (at least not per resident), the officer likes the additional income, and the residents feel safer. Such arrangements are probably more successful than hiring private watchmen, and the Newark experiment helps us understand why. A private security guard may deter crime or misconduct by his presence, and he may go to the aid of persons needing help, but he may well not intervene—that is, control or drive away—someone challenging community standards. Being a sworn officer—a «real cop»—seems to give one the confidence, the sense of duty, and the aura of authority necessary to perform this difficult task.

Patrol officers might be encouraged to go to and from duty stations on public transportation and, while on the bus or subway car, enforce rules about smoking, drinking, disorderly conduct, and the like. The enforcement need involve nothing more than ejecting the offender (the offense, after all, is not one with which a booking officer or a judge wishes to be bothered). Perhaps the random but relentless maintenance of standards on buses would lead to conditions on buses that approximate the level of civility we now take for granted on airplanes.

But the most important requirement is to think that to maintain order in precarious situations is a vital job. The police know this is one of their functions, and they also believe, correctly, that it cannot be done to the exclusion of criminal investigation and responding to calls. We may have encouraged them to suppose, however, on the basis of our oft-repeated concerns about serious, violent crime, that they will be judged exclusively on their capacity as crime-fighters. To the extent that this is the case, police administrators will continue to concentrate police personnel in the highest-crime areas (though not necessarily in the areas most vulnerable to criminal invasion), emphasize their training in the law and criminal apprehension (and not their training in managing street life), and join too quickly in campaigns to decriminalize «harmless» behavior (though public drunkenness, street prostitution, and pornographic displays can destroy a community more quickly than any team of professional burglars).

Above all, we must return to our long-abandoned view that the police ought to protect communities as well as individuals. Our crime statistics and victimization surveys measure individual losses, but they do not measure communal losses. Just as physicians now recognize the importance of fostering health rather than simply treating illness, so the police—and the rest of us—ought to recognize the importance of maintaining, intact, communities without broken windows.

In criminology, the broken windows theory states that visible signs of crime, anti-social behavior and civil disorder create an urban environment that encourages further crime and disorder, including serious crimes.[1] The theory suggests that policing methods that target minor crimes such as vandalism, loitering, public drinking, jaywalking, and fare evasion help to create an atmosphere of order and lawfulness.

The theory was introduced in a 1982 article by social scientists James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling.[1] It was popularized in the 1990s by New York City police commissioner William Bratton and mayor Rudy Giuliani, whose policing policies were influenced by the theory.

The theory became subject to debate both within the social sciences and the public sphere. Broken windows policing has been enforced with controversial police practices, such as the high use of stop-and-frisk in New York City in the decade up to 2013. In response, Bratton and Kelling have written that broken windows policing should not be treated as «zero tolerance» or «zealotry», but as a method that requires «careful training, guidelines, and supervision» and a positive relationship with communities, thus linking it to community policing.[2]

Article and crime preventionEdit

James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling first introduced the broken windows theory in an article titled «Broken Windows», in the March 1982 issue of The Atlantic Monthly.

Social psychologists and police officers tend to agree that if a window in a building is broken and is left unrepaired, all the rest of the windows will soon be broken. This is as true in nice neighborhoods as in rundown ones. Window-breaking does not necessarily occur on a large scale because some areas are inhabited by determined window-breakers whereas others are populated by window-lovers; rather, one un-repaired broken window is a signal that no one cares, and so breaking more windows costs nothing. (It has always been fun.)[1]

The article received a great deal of attention and was very widely cited. A 1996 criminology and urban sociology book, Fixing Broken Windows: Restoring Order and Reducing Crime in Our Communities by George L. Kelling and Catharine Coles, is based on the article but develops the argument in greater detail. It discusses the theory in relation to crime and strategies to contain or eliminate crime from urban neighborhoods.[3]

A successful strategy for preventing vandalism, according to the book’s authors, is to address the problems when they are small. Repair the broken windows within a short time, say, a day or a week, and the tendency is that vandals are much less likely to break more windows or do further damage. Clean up the sidewalk every day, and the tendency is for litter not to accumulate (or for the rate of littering to be much less). Problems are less likely to escalate and thus respectable residents do not flee the neighborhood.

Oscar Newman introduced defensible space theory in his 1972 book Defensible Space. He argued that although police work is crucial to crime prevention, police authority is not enough to maintain a safe and crime-free city. People in the community help with crime prevention. Newman proposed that people care for and protect spaces that they feel invested in, arguing that an area is eventually safer if the people feel a sense of ownership and responsibility towards the area. Broken windows and vandalism are still prevalent because communities simply do not care about the damage. Regardless of how many times the windows are repaired, the community still must invest some of their time to keep it safe. Residents’ negligence of broken window-type decay signifies a lack of concern for the community. Newman says this is a clear sign that the society has accepted this disorder—allowing the unrepaired windows to display vulnerability and lack of defense.[4] Malcolm Gladwell also relates this theory to the reality of New York City in his book, The Tipping Point.[5]

Thus, the theory makes a few major claims: that improving the quality of the neighborhood environment reduces petty crime, anti-social behavior, and low-level disorder, and that major crime is also prevented as a result. Criticism of the theory has tended to focus on the latter claim.[6]

Theoretical explanationEdit

The reason the state of the urban environment may affect crime consists of three factors: social norms and conformity; the presence or lack of routine monitoring; and social signaling and signal crime.

In an anonymous urban environment, with few or no other people around, social norms and monitoring are not clearly known. Thus, individuals look for signals within the environment as to the social norms in the setting and the risk of getting caught violating those norms; one of the signals is the area’s general appearance.

Under the broken windows theory, an ordered and clean environment, one that is maintained, sends the signal that the area is monitored and that criminal behavior is not tolerated. Conversely, a disordered environment, one that is not maintained (broken windows, graffiti, excessive litter), sends the signal that the area is not monitored and that criminal behavior has little risk of detection.

The theory assumes that the landscape «communicates» to people. A broken window transmits to criminals the message that a community displays a lack of informal social control and so is unable or unwilling to defend itself against a criminal invasion. It is not so much the actual broken window that is important, but the message the broken window sends to people. It symbolizes the community’s defenselessness and vulnerability and represents the lack of cohesiveness of the people within. Neighborhoods with a strong sense of cohesion fix broken windows and assert social responsibility on themselves, effectively giving themselves control over their space.

The theory emphasizes the built environment, but must also consider human behavior.[7]

Under the impression that a broken window left unfixed leads to more serious problems, residents begin to change the way they see their community. In an attempt to stay safe, a cohesive community starts to fall apart, as individuals start to spend less time in communal space to avoid potential violent attacks by strangers.[1] The slow deterioration of a community, as a result of broken windows, modifies the way people behave when it comes to their communal space, which, in turn, breaks down community control. As rowdy teenagers, panhandlers, addicts, and prostitutes slowly make their way into a community, it signifies that the community cannot assert informal social control, and citizens become afraid that worse things will happen. As a result, they spend less time in the streets to avoid these subjects and feel less and less connected from their community, if the problems persist.

At times, residents tolerate «broken windows» because they feel they belong in the community and «know their place». Problems, however, arise when outsiders begin to disrupt the community’s cultural fabric. That is the difference between «regulars» and «strangers» in a community. The way that «regulars» act represents the culture within, but strangers are «outsiders» who do not belong.[7]

Consequently, daily activities considered «normal» for residents now become uncomfortable, as the culture of the community carries a different feel from the way that it was once.

With regard to social geography, the broken windows theory is a way of explaining people and their interactions with space. The culture of a community can deteriorate and change over time, with the influence of unwanted people and behaviors changing the landscape. The theory can be seen as people shaping space, as the civility and attitude of the community create spaces used for specific purposes by residents. On the other hand, it can also be seen as space shaping people, with elements of the environment influencing and restricting day-to-day decision making.

However, with policing efforts to remove unwanted disorderly people that put fear in the public’s eyes, the argument would seem to be in favor of «people shaping space», as public policies are enacted and help to determine how one is supposed to behave. All spaces have their own codes of conduct, and what is considered to be right and normal will vary from place to place.

The concept also takes into consideration spatial exclusion and social division, as certain people behaving in a given way are considered disruptive and therefore, unwanted. It excludes people from certain spaces because their behavior does not fit the class level of the community and its surroundings. A community has its own standards and communicates a strong message to criminals, by social control, that their neighborhood does not tolerate their behavior. If, however, a community is unable to ward off would-be criminals on their own, policing efforts help.

By removing unwanted people from the streets, the residents feel safer and have a higher regard for those that protect them. People of less civility who try to make a mark in the community are removed, according to the theory.[7]

ConceptsEdit

Edit

Many claim that informal social control can be an effective strategy to reduce unruly behavior. Garland (2001) expresses that «community policing measures in the realization that informal social control exercised through everyday relationships and institutions is more effective than legal sanctions.»[8] Informal social control methods have demonstrated a «get tough» attitude by proactive citizens, and express a sense that disorderly conduct is not tolerated. According to Wilson and Kelling, there are two types of groups involved in maintaining order, ‘community watchmen’ and ‘vigilantes’.[1] The United States has adopted in many ways policing strategies of old European times, and at that time, informal social control was the norm, which gave rise to contemporary formal policing. Though, in earlier times, because there were no legal sanctions to follow, informal policing was primarily ‘objective’ driven, as stated by Wilson and Kelling (1982).

Wilcox et al. 2004 argue that improper land use can cause disorder, and the larger the public land is, the more susceptible to criminal deviance.[9] Therefore, nonresidential spaces, such as businesses, may assume to the responsibility of informal social control «in the form of surveillance, communication, supervision, and intervention».[10] It is expected that more strangers occupying the public land creates a higher chance for disorder. Jane Jacobs can be considered one of the original pioneers of this perspective of broken windows. Much of her book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, focuses on residents’ and nonresidents’ contributions to maintaining order on the street, and explains how local businesses, institutions, and convenience stores provide a sense of having «eyes on the street».[11]

On the contrary, many residents feel that regulating disorder is not their responsibility. Wilson and Kelling found that studies done by psychologists suggest people often refuse to go to the aid of someone seeking help, not due to a lack of concern or selfishness «but the absence of some plausible grounds for feeling that one must personally accept responsibility».[1] On the other hand, others plainly refuse to put themselves in harm’s way, depending on how grave they perceive the nuisance to be; a 2004 study observed that «most research on disorder is based on individual level perceptions decoupled from a systematic concern with the disorder-generating environment.»[12] Essentially, everyone perceives disorder differently, and can contemplate seriousness of a crime based on those perceptions. However, Wilson and Kelling feel that although community involvement can make a difference, «the police are plainly the key to order maintenance.»[1]

Role of fearEdit

Ranasinghe argues that the concept of fear is a crucial element of broken windows theory, because it is the foundation of the theory.[13] She also adds that public disorder is «… unequivocally constructed as problematic because it is a source of fear».[14] Fear is elevated as perception of disorder rises; creating a social pattern that tears the social fabric of a community, and leaves the residents feeling hopeless and disconnected. Wilson and Kelling hint at the idea, but do not focus on its central importance. They indicate that fear was a product of incivility, not crime, and that people avoid one another in response to fear, weakening controls.[1] Hinkle and Weisburd found that police interventions to combat minor offenses, as per the broken windows model, «significantly increased the probability of feeling unsafe,» suggesting that such interventions might offset any benefits of broken windows policing in terms of fear reduction.[15]

Difference with «zero tolerance»Edit

Broken windows policing is sometimes described as a «zero tolerance» policing style,[16] including in some academic studies.[17] However, several key proponents, such as Bratton and Kelling, argue that there is a key difference. In 2014, they outlined a difference between «broken windows policing» and «zero tolerance»:

Critics use the term «zero tolerance» in a pejorative sense to suggest that Broken Windows policing is a form of zealotry—the imposition of rigid, moralistic standards of behavior on diverse populations. It is not. Broken Windows is a highly discretionary police activity that requires careful training, guidelines, and supervision, as well as an ongoing dialogue with neighborhoods and communities to ensure that it is properly conducted.[2]

Bratton and Kelling advocate that authorities should be effective at catching minor offenders while also giving them lenient punishment. Citing fare evasion, as an example, they argue that the police should attempt to catch fare evaders, and that the vast majority should be summoned to court rather than arrested and given a punishment other than jail. The goal is to deter minor offenders from committing more serious crimes in the future and reduce the prison population in the long run.[2]

Critical developmentsEdit

In an earlier publication of The Atlantic released March, 1982, Wilson wrote an article indicating that police efforts had gradually shifted from maintaining order to fighting crime.[1] This indicated that order maintenance was something of the past, and soon it would seem as it has been put on the back burner. The shift was attributed to the rise of the social urban riots of the 1960s, and «social scientists began to explore carefully the order maintenance function of the police, and to suggest ways of improving it—not to make streets safer (its original function) but to reduce the incidence of mass violence».[1] Other criminologists argue between similar disconnections, for example, Garland argues that throughout the early and mid 20th century, police in American cities strived to keep away from the neighborhoods under their jurisdiction.[8] This is a possible indicator of the out-of-control social riots that were prevalent at that time.[citation needed] Still many would agree that reducing crime and violence begins with maintaining social control/order.[18]

Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities is discussed in detail by Ranasinghe, and its importance to the early workings of broken windows, and claims that Kelling’s original interest in «minor offences and disorderly behaviour and conditions» was inspired by Jacobs’ work.[19] Ranasinghe includes that Jacobs’ approach toward social disorganization was centralized on the «streets and their sidewalks, the main public places of a city» and that they «are its most vital organs, because they provide the principal visual scenes».[20] Wilson and Kelling, as well as Jacobs, argue on the concept of civility (or the lack thereof) and how it creates lasting distortions between crime and disorder. Ranasinghe explains that the common framework of both set of authors is to narrate the problem facing urban public places. Jacobs, according to Ranasinghe, maintains that «Civility functions as a means of informal social control, subject little to institutionalized norms and processes, such as the law» ‘but rather maintained through an’ «intricate, almost unconscious, network of voluntary controls and standards among people… and enforced by the people themselves».[21]

Case studiesEdit

Precursor experimentsEdit

Before the introduction of this theory by Wilson and Kelling, Philip Zimbardo, a Stanford psychologist, arranged an experiment testing the broken-window theory in 1969. Zimbardo arranged for an automobile with no license plates and the hood up to be parked idle in a Bronx neighbourhood and a second automobile, in the same condition, to be set up in Palo Alto, California. The car in the Bronx was attacked within minutes of its abandonment. Zimbardo noted that the first «vandals» to arrive were a family—a father, mother, and a young son—who removed the radiator and battery. Within twenty-four hours of its abandonment, everything of value had been stripped from the vehicle. After that, the car’s windows were smashed in, parts torn, upholstery ripped, and children were using the car as a playground. At the same time, the vehicle sitting idle in Palo Alto sat untouched for more than a week until Zimbardo himself went up to the vehicle and deliberately smashed it with a sledgehammer. Soon after, people joined in for the destruction, although criticism has been levelled at this claim as the destruction occurred after the car was moved to the campus of Stanford university and Zimbardo’s own students were the first to join him. Zimbardo observed that a majority of the adult «vandals» in both cases were primarily well dressed, Caucasian, clean-cut and seemingly respectable individuals. It is believed that, in a neighborhood such as the Bronx where the history of abandoned property and theft is more prevalent, vandalism occurs much more quickly, as the community generally seems apathetic. Similar events can occur in any civilized community when communal barriers—the sense of mutual regard and obligations of civility—are lowered by actions that suggest apathy.[1][22]

New York CityEdit

In 1985, the New York City Transit Authority hired George L. Kelling, the author of Broken Windows, as a consultant.[23] Kelling was later hired as a consultant to the Boston and the Los Angeles police departments.

One of Kelling’s adherents, David L. Gunn, implemented policies and procedures based on the Broken Windows Theory, during his tenure as President of the New York City Transit Authority. One of his major efforts was to lead a campaign from 1984 to 1990 to rid graffiti from New York’s subway system.

In 1990, William J. Bratton became head of the New York City Transit Police. Bratton was influenced by Kelling, describing him as his «intellectual mentor». In his role, he implemented a tougher stance on fare evasion, faster arrestee processing methods, and background checks on all those arrested.

After being elected Mayor of New York City in 1993, as a Republican, Rudy Giuliani hired Bratton as his police commissioner to implement similar policies and practices throughout the city. Giuliani heavily subscribed to Kelling and Wilson’s theories. Such policies emphasized addressing crimes that negatively affect quality of life. In particular, Bratton directed the police to more strictly enforce laws against subway fare evasion, public drinking, public urination, and graffiti. Bratton also revived the New York City Cabaret Law, a previously dormant Prohibition era ban on dancing in unlicensed establishments. Throughout the late 1990s, NYPD shut down many of the city’s acclaimed night spots for illegal dancing.

According to a 2001 study of crime trends in New York City by Kelling and William Sousa, rates of both petty and serious crime fell significantly after the aforementioned policies were implemented. Furthermore, crime continued to decline for the following ten years. Such declines suggested that policies based on the Broken Windows Theory were effective.[24]

However, other studies do not find a cause and effect relationship between the adoption of such policies and decreases in crime.[6][25] The decrease may have been part of a broader trend across the United States. The rates of most crimes, including all categories of violent crime, made consecutive declines from their peak in 1990, under Giuliani’s predecessor, David Dinkins. Other cities also experienced less crime, even though they had different police policies. Other factors, such as the 39% drop in New York City’s unemployment rate between 1992 and 1999,[26] could also explain the decrease reported by Kelling and Sousa.[26]

A 2017 study found that when the New York Police Department (NYPD) stopped aggressively enforcing minor legal statutes in late 2014 and early 2015 that civilian complaints of three major crimes (burglary, felony assault, and grand larceny) decreased (slightly with large error bars) during and shortly after sharp reductions in proactive policing. There was no statistically significant effect on other major crimes such as murder, rape, robbery, or grand theft auto. These results are touted as challenging prevailing scholarship as well as conventional wisdom on authority and legal compliance by implying that aggressively enforcing minor legal statutes incites more severe criminal acts.[27]

AlbuquerqueEdit

Albuquerque, New Mexico, instituted the Safe Streets Program in the late 1990s based on the Broken Windows Theory. The Safe Streets Program sought to deter and reduce unsafe driving and incidence of crime by saturating areas where high crime and crash rates were prevalent with law enforcement officers. Operating under the theory that American Westerners use roadways much in the same way that American Easterners use subways, the developers of the program reasoned that lawlessness on the roadways had much the same effect as it did on the New York City Subway. Effects of the program were reviewed by the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and were published in a case study.[28] The methodology behind the program demonstrates the use of deterrence theory in preventing crime.[29]

Lowell, MassachusettsEdit

In 2005, Harvard University and Suffolk University researchers worked with local police to identify 34 «crime hot spots» in Lowell, Massachusetts. In half of the spots, authorities cleared trash, fixed streetlights, enforced building codes, discouraged loiterers, made more misdemeanor arrests, and expanded mental health services and aid for the homeless. In the other half of the identified locations, there was no change to routine police service.

The areas that received additional attention experienced a 20% reduction in calls to the police. The study concluded that cleaning up the physical environment was more effective than misdemeanor arrests and that increasing social services had no effect.[30][31]

NetherlandsEdit

In 2007 and 2008, Kees Keizer and colleagues from the University of Groningen conducted a series of controlled experiments to determine if the effect of existing visible disorder (such as litter or graffiti) increased other crime such as theft, littering, or other antisocial behavior. They selected several urban locations, which they arranged in two different ways, at different times. In each experiment, there was a «disorder» condition in which violations of social norms as prescribed by signage or national custom, such as graffiti and littering, were clearly visible as well as a control condition where no violations of norms had taken place. The researchers then secretly monitored the locations to observe if people behaved differently when the environment was «disordered». Their observations supported the theory. The conclusion was published in the journal Science: «One example of disorder, like graffiti or littering, can indeed encourage another, like stealing.»[32][33]

Other effectsEdit

Real estateEdit

Other side effects of better monitoring and cleaned up streets may well be desired by governments or housing agencies and the population of a neighborhood: broken windows can count as an indicator of low real estate value and may deter investors. It is recommended[by whom?] that real estate consider adopting the «Broken Windows Theory», because if they monitor the amount of minor transgressions in a specific area, they are most likely to experience a reduction in major transgressions as well. This may actually increase or decrease value in a house or apartment, depending on the area.[34] Fixing windows is therefore also a step of real estate development, which may lead, whether it is desired or not, to gentrification. By reducing the amount of broken windows in the community, the inner cities would appear to be attractive to consumers with more capital. Ridding spaces like downtown New York and Chicago, notably notorious for criminal activity, of danger would draw in investment from consumers, increasing the city’s economic status, providing a safe and pleasant image for present and future inhabitants.[25]

EducationEdit

In education, the broken windows theory is used to promote order in classrooms and school cultures. The belief is that students are signaled by disorder or rule-breaking and that they in turn imitate the disorder. Several school movements encourage strict paternalistic practices to enforce student discipline. Such practices include language codes (governing slang, curse words, or speaking out of turn), classroom etiquette (sitting up straight, tracking the speaker), personal dress (uniforms, little or no jewelry), and behavioral codes (walking in lines, specified bathroom times).

From 2004 to 2006, Stephen B. Plank and colleagues from Johns Hopkins University conducted a correlational study to determine the degree to which the physical appearance of the school and classroom setting influence student behavior, particularly in respect to the variables concerned in their study: fear, social disorder, and collective efficacy.[35] They collected survey data administered to 6th-8th students by 33 public schools in a large mid-Atlantic city. From analyses of the survey data, the researchers determined that the variables in their study are statistically significant to the physical conditions of the school and classroom setting. The conclusion, published in the American Journal of Education, was

…the findings of the current study suggest that educators and researchers should be vigilant about factors that influence student perceptions of climate and safety. Fixing broken windows and attending to the physical appearance of a school cannot alone guarantee productive teaching and learning, but ignoring them likely greatly increases the chances of a troubling downward spiral.[35]

Statistical evidenceEdit

A 2015 meta-analysis of broken windows policing implementations found that disorder policing strategies, such as «hot spots policing» or problem-oriented policing, result in «consistent crime reduction effects across a variety of violent, property, drug, and disorder outcome measures».[36] However, the authors noted that «aggressive order maintenance strategies that target individual disorderly behaviors do not generate significant crime reductions,» pointing specifically to zero tolerance policing models that target singular behaviors such as public intoxication and remove disorderly individuals from the street via arrest. The authors recommend that police develop «community co-production» policing strategies instead of merely committing to increasing misdemeanor arrests.[36]

CriticismEdit

Other factorsEdit

Several studies have argued that many of the apparent successes of broken windows policing (such as New York City in the 1990s) were the result of other factors.[37] They claim that the «broken windows theory» closely relates correlation with causality, a reasoning prone to fallacy. David Thacher, assistant professor of public policy and urban planning at the University of Michigan, stated in a 2004 paper:[37]

[S]ocial science has not been kind to the broken windows theory. A number of scholars reanalyzed the initial studies that appeared to support it…. Others pressed forward with new, more sophisticated studies of the relationship between disorder and crime. The most prominent among them concluded that the relationship between disorder and serious crime is modest, and even that relationship is largely an artifact of more fundamental social forces.

C. R. Sridhar, in his article in the Economic and Political Weekly, also challenges the theory behind broken windows policing and the idea that the policies of William Bratton and the New York Police Department was the cause of the decrease of crime rates in New York City.[17] The policy targeted people in areas with a significant amount of physical disorder and there appeared to be a causal relationship between the adoption of broken windows policing and the decrease in crime rate. Sridhar, however, discusses other trends (such as New York City’s economic boom in the late 1990s) that created a «perfect storm» that contributed to the decrease of crime rate much more significantly than the application of the broken windows policy. Sridhar also compares this decrease of crime rate with other major cities that adopted other various policies and determined that the broken windows policy is not as effective.

In a 2007 study called «Reefer Madness» in the journal Criminology and Public Policy, Harcourt and Ludwig found further evidence confirming that mean reversion fully explained the changes in crime rates in the different precincts in New York in the 1990s.[38] Further alternative explanations that have been put forward include the waning of the crack epidemic,[39] unrelated growth in the prison population by the Rockefeller drug laws,[39] and that the number of males from 16 to 24 was dropping regardless of the shape of the US population pyramid.[40]

It has also been argued that rates of major crimes also dropped in many other US cities during the 1990s, both those that had adopted broken windows policing and those that had not.[41] In the winter 2006 edition of the University of Chicago Law Review, Bernard Harcourt and Jens Ludwig looked at the later Department of Housing and Urban Development program that rehoused inner-city project tenants in New York into more-orderly neighborhoods.[25] The broken windows theory would suggest that these tenants would commit less crime once moved because of the more stable conditions on the streets. However, Harcourt and Ludwig found that the tenants continued to commit crime at the same rate.

Baltimore criminologist Ralph B. Taylor argues in his book that fixing windows is only a partial and short-term solution. His data supports a materialist view: changes in levels of physical decay, superficial social disorder, and racial composition do not lead to higher crime, but economic decline does. He contends that the example shows that real, long-term reductions in crime require that urban politicians, businesses, and community leaders work together to improve the economic fortunes of residents in high-crime areas.[42]

In 2015, Northeastern University assistant professor Daniel T. O’Brien criticised the broken theory model. Using his Big Data based research model, he argues that the broken window model fails to capture the origins of crime in a neighbourhood. He concludes that crime comes from the social dynamics of communities and private spaces and spills out into public spaces [43]

Relationship between crime and disorderEdit

According to a study by Robert J. Sampson and Stephen Raudenbush, the premise on which the theory operates, that social disorder and crime are connected as part of a causal chain, is faulty. They argue that a third factor, collective efficacy, «defined as cohesion among residents combined with shared expectations for the social control of public space,» is the actual cause of varying crime rates that are observed in an altered neighborhood environment. They also argue that the relationship between public disorder and crime rate is weak.[44]

Another tack was taken by a 2010 study questioning the legitimacy of the theory concerning the subjectivity of disorder as perceived by persons living in neighborhoods. It concentrated on whether citizens view disorder as a separate issue from crime or as identical to it. The study noted that crime cannot be the result of disorder if the two are identical, agreed that disorder provided evidence of «convergent validity» and concluded that broken windows theory misinterprets the relationship between disorder and crime.[45]

Racial biasEdit

Broken windows policing has sometimes become associated with zealotry, which has led to critics suggesting that it encourages discriminatory behaviour. Some campaigns such as Black Lives Matter have called for an end to broken windows policing.[46] In 2016, a Department of Justice report argued that it had led the Baltimore Police Department discriminating against and alienating minority groups.[47]

A central argument is that the concept of disorder is vague, and giving the police broad discretion to decide what disorder is will lead to discrimination. In Dorothy Roberts’s article, «Foreword: Race, Vagueness, and the Social Meaning of Order Maintenance and Policing», she says that broken windows theory in practice leads to the criminalization of communities of color, who are typically disfranchised.[48] She underscores the dangers of vaguely written ordinances that allows for law enforcers to determine who engages in disorderly acts, which, in turn, produce a racially skewed outcome in crime statistics.[49] Similarly, Gary Stewart wrote, «The central drawback of the approaches advanced by Wilson, Kelling, and Kennedy rests in their shared blindness to the potentially harmful impact of broad police discretion on minority communities.»[50] It was seen by the authors, who worried that people would be arrested «for the ‘crime’ of being undesirable». According to Stewart, arguments for low-level police intervention, including the broken windows hypothesis, often act «as cover for racist behavior».[50]

The theory has also been criticized for its unsound methodology and its manipulation of racialized tropes. Specifically, Bench Ansfield has shown that in their 1982 article, Wilson and Kelling cited only one source to prove their central contention that disorder leads to crime: the Philip Zimbardo vandalism study (see Precursor Experiments above).[51] But Wilson and Kelling misrepresented Zimbardo’s procedure and conclusions, dispensing with Zimbardo’s critique of inequality and community anonymity in favor of the oversimplified claim that one broken window gives rise to «a thousand broken windows». Ansfield argues that Wilson and Kelling used the image of the crisis-ridden 1970s Bronx to stoke fears that «all cities would go the way of the Bronx if they didn’t embrace their new regime of policing.»[52] Wilson and Kelling manipulated the Zimbardo experiment to avail themselves of the racialized symbolism found in the broken windows of the Bronx.[51]

Robert J. Sampson argues that based on common misconceptions by the masses, it is clearly implied that those who commit disorder and crime have a clear tie to groups suffering from financial instability and may be of minority status: «The use of racial context to encode disorder does not necessarily mean that people are racially prejudiced in the sense of personal hostility.» He notes that residents make a clear implication of who they believe is causing the disruption, which has been termed as implicit bias.[53] He further states that research conducted on implicit bias and stereotyping of cultures suggests that community members hold unrelenting beliefs of African-Americans and other disadvantaged minority groups, associating them with crime, violence, disorder, welfare, and undesirability as neighbors.[53] A later study indicated that this contradicted Wilson and Kelling’s proposition that disorder is an exogenous construct that has independent effects on how people feel about their neighborhoods.[45]

In response, Kelling and Bratton have argued that broken windows policing does not discriminate against law-abiding communities of minority groups if implemented properly.[2] They cited Disorder and Decline: Crime and the Spiral of Decay in American Neighborhoods,[54] a study by Wesley Skogan at Northwestern University. The study, which surveyed 13,000 residents of large cities, concluded that different ethnic groups have similar ideas as to what they would consider to be «disorder».

Minority groups have tended to be targeted at higher rates by the Broken Windows style of policing. Broken Windows policies have been utilized more heavily in minority neighborhoods where low-income, poor infrastructure, and social disorder were widespread, causing minority groups to perceive that they were being racially profiled under Broken Windows policing.[23][55]

Class biasEdit

Homeless man talking with a police officer