I’m trying to create and activate a virtual environment, using Windows 10 command prompt. I know that virtualenv is installed correctly, as the command

virtualenv venv

Works. I’ve navigated to my virtualenv download, DownloadsvenvScripts, and am trying to activate my virtual environment venv. I’ve tried

venv activate

Which doesn’t work since Windows doesn’t recognize venv as a command. I’ve also tried

virtualenv venv activate

Which also doesn’t work since virtualenv is saying that «venv activate» isn’t a valid argument.

asked Oct 23, 2017 at 18:26

1

Use the activate script in the Scripts directory of your virtual environment:

> venvScriptsactivate

This will activate your virtual environment and your terminal will look like this depending on the directory you’re in:

(venv) C:UsersacerDesktop>

I hope this helps!

tim-kt

3046 silver badges17 bronze badges

answered May 8, 2020 at 12:54

3

If you’re using virtualenvwrapper-win, and using the DOS command prompt (as opposed to e.g. Powershell), then new virtualenvs are created using:

mkvirtualenv myenv

and activated using

workon myenv

You should define the environment variable WORKON_HOME to point to where you want you virtualenvs to reside.

If you’ve installed virtualenvwrapper-win>=1.2.4 then the virtualenvwrapper command will give you a list available commands:

go|c:srv> virtualenvwrapper

virtualenvwrapper is a set of extensions to Ian Bicking's virtualenv

tool. The extensions include wrappers for creating and deleting

virtual environments and otherwise managing your development workflow,

making it easier to work on more than one project at a time without

introducing conflicts in their dependencies.

virtualenvwrapper-win is a port of Dough Hellman's virtualenvwrapper to Windows

batch scripts.

Commands available:

add2virtualenv: add directory to the import path

cdproject: change directory to the active project

cdsitepackages: change to the site-packages directory

cdvirtualenv: change to the $VIRTUAL_ENV directory

lssitepackages: list contents of the site-packages directory

lsvirtualenv: list virtualenvs

mkproject: create a new project directory and its associated virtualenv

mkvirtualenv: Create a new virtualenv in $WORKON_HOME

rmvirtualenv: Remove a virtualenv

setprojectdir: associate a project directory with a virtualenv

toggleglobalsitepackages: turn access to global site-packages on/off

virtualenvwrapper: show this help message

whereis: return full path to executable on path.

workon: list or change working virtualenvs

answered Dec 1, 2017 at 23:47

thebjornthebjorn

25.7k10 gold badges92 silver badges135 bronze badges

From the directory where you have your virtual environment (e.g. myenv)

you need to run the following command: .myenvScriptsactivate

answered Oct 12, 2021 at 13:23

Go to the folder where you have created the virtual environment in cmd and

enter the command .venvScriptsactivate

It will activate the virtual env in windows

pegah

7318 silver badges15 bronze badges

answered Sep 12, 2021 at 10:30

from the command (cmd) prompt:

call venv/Scripts/activate

D.L

3,7574 gold badges20 silver badges39 bronze badges

answered Aug 27, 2022 at 14:09

0

Make sure the Python Scripts folder is in your environment variables.

Usually the path is: «C:UsersadminAppDataLocalProgramsPythonPython37-32Scripts»

(Change «admin» to your windows username and «Python37-32» path according to your python version)

answered Jan 22, 2019 at 7:38

Deep ShahDeep Shah

1012 silver badges7 bronze badges

When you use «virtualenv» to create an env, it saves an «activate.bat» file in the scripts folder originating from the directory you ran the first command. E.g if you ran the command virtualenv env from C:/Users/Name/Documents/..., the .bat will be located in C:/Users/Name/Documents/.../env/scripts/activate.bat. You can run it from there.

Jawad

10.9k3 gold badges23 silver badges36 bronze badges

answered Jan 21, 2020 at 15:12

Simply you can activate your virtualenv using command: workon myenvname

answered Jun 6, 2020 at 6:27

You can also create a command-line script like this —

@echo off

CD

CD "C:Users[user name]venvScripts"

start activate.bat

start jupyter notebook

Save this in a notepad file with an extension «.cmd».

You are ready to go

answered Sep 19, 2020 at 18:26

if you have anaconda installed then open anaconda terminal and type

> conda env list # for list of environment you already have

> conda activate {env_name} # to activate the environment

answered Jan 5, 2021 at 10:46

VikasKMVikasKM

1923 silver badges6 bronze badges

This works for me from Anaconda prompt,

.\myvenv\Scripts\activate.bat

answered Jan 31, 2021 at 18:05

MohitMohit

1,0354 gold badges18 silver badges45 bronze badges

- start python 3.7

python -m virtualenv

"You must provide a DEST_DIR"python -m venv demodjango("demodjango is file name)"activate.batpip install djangodjango-admin.py startproject demo1(demo1 is my project)python manage.py runserver

Performing system checks...- After doing this on a command prompt, you will get an URL. Click on that and you will see a message in the browser window that Django has been properly installed.

Simon Zyx

6,1331 gold badge24 silver badges36 bronze badges

answered Nov 6, 2018 at 19:09

VivekVivek

31 silver badge4 bronze badges

How to connect create a Python Virtual Environment

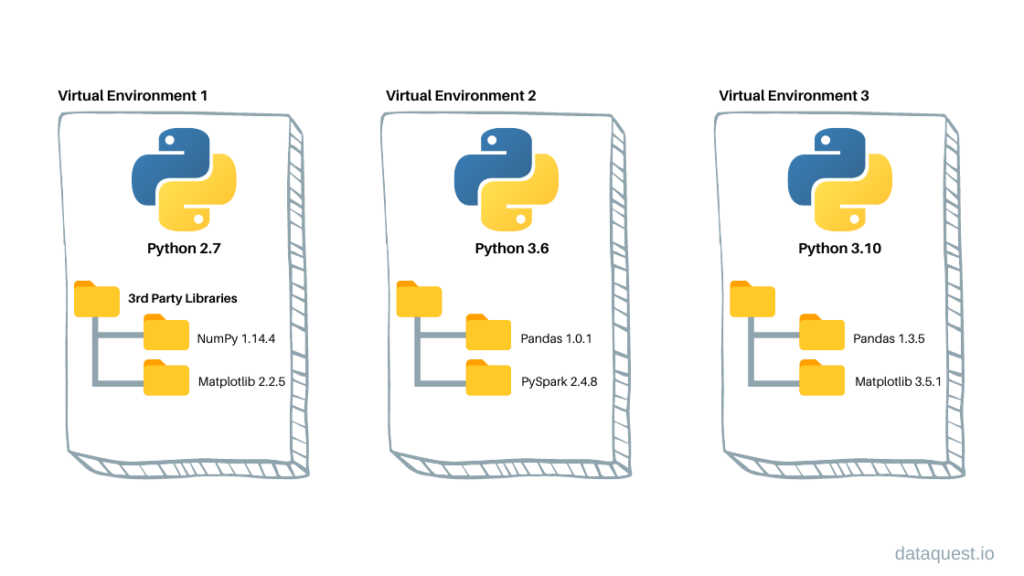

It is often useful to have one or more Python environments where you can experiment with different combinations of packages without affecting your main installation. Python supports this through virtual environments. The virtual environment is a copy of an existing version of Python with the option to inherit existing packages. A virtual environment is also useful when you need to work on a shared system and do not have permission to install packages as you will be able to install them in the virtual environment.

Outline

- Open a terminal

- Setup the pip package manager

- Install the virtualenv package

- Create the virtual environment

- Activate the virtual environment

- Deactivate the virtual environment

- Optional: Make the virtual environment your default Python

- More: Python virtualenv documentation

Requirements

- An installation of Python

Jargon

Link to Jargon page with terms: terminal

Open a terminal

The method you use to open a terminal depends on your operating system.

Windows

Open the Windows Command Prompt (show path via Start menu and keyboard shortcuts)

Mac OS / Linux

Open the Terminal program. This is usually found under Utilities or Accessories.

Setup the pip package manager

Check to see if your Python installation has pip. Enter the following in your terminal:

If you see the help text for pip then you have pip installed, otherwise download and install pip

Install the virtualenv package

The virtualenv package is required to create virtual environments. You can install it with pip:

Create the virtual environment

To create a virtual environment, you must specify a path. For example to create one in the local directory called ‘mypython’, type the following:

Activate the virtual environment

You can activate the python environment by running the following command:

Mac OS / Linux

source mypython/bin/activateWindows

You should see the name of your virtual environment in brackets on your terminal line e.g. (mypython).

Any python commands you use will now work with your virtual environment

Deactivate the virtual environment

To decativate the virtual environment and use your original Python environment, simply type ‘deactivate’.

Optional: Make the virtual environment your default Python

More: Python virtualenv documentation

For more detailed information, see the offical virtualenv documentation

Python virtual environments allow you to install Python packages in an isolated location from the rest of your system instead of installing them system-wide. Let’s look at how to use the Python venv, short for Python virtual environment, also abbreviated as virtualenv.

In this article, you will learn:

- The advantages of using virtual environments

- How to create a venv

- How to activate and deactivate it

- Different ways to delete or remove a venv

- How a venv works internally

If you have some time to spare, please consider my Python Fundamentals II course to learn about virtual environments and get hands-on, real-world practice. It’s a deep dive into modules, packages, virtual environments, and package managers.

Table of Contents

- 1 Why you need virtual environments

- 2 Virtual environments vs. other options

- 3 How to create a Python venv

- 4 Python venv activation

- 5 How a Python venv works

- 6 Deactivate the Python venv

- 7 Deleting a Python venv

- 8 Conclusion

- 9 Keep learning

Why you need virtual environments

There are multiple reasons why virtual environments are a good idea, and this is also the reason why I’m telling you about them before we continue to the part where we start installing 3rd party packages. Let’s go over them one by one.

Preventing version conflicts

You could argue that installing third-party packages system-wide is very efficient. After all, you only need to install it once and can use the package from multiple Python projects, saving you precious time and disk space. There’s a problem with this approach that may start to unfold weeks or months later, however.

Suppose your project, Project A, is written against a specific version of library X. In the future, you might need to upgrade library X. Say, for example, you need the latest version for another project you started, called Project B. You upgrade library X to the latest version, and project B works fine. Great! But once you did this, it turns out your Project A code broke badly. After all, APIs can change significantly on major version upgrades.

A virtual environment fixes this problem by isolating your project from other projects and system-wide packages. You install packages inside this virtual environment specifically for the project you are working on.

Easy to reproduce and install

Virtual environments make it easy to define and install the packages specific to your project. Using a requirements.txt file, you can define exact version numbers for the required packages to ensure your project will always work with a version tested with your code. This also helps other users of your software since a virtual environment helps others reproduce the exact environment for which your software was built.

Works everywhere, even when not administrator (root)

If you’re working on a shared host, like those at a university or a web hosting provider, you won’t be able to install system-wide packages since you don’t have the administrator rights to do so. In these places, a virtual environment allows you to install anything you want locally in your project.

Virtual environments vs. other options

There are other options to isolate your project:

- In the most extreme case, you could buy a second PC and run your code there. Problem fixed! It was a bit expensive, though!

- A virtual machine is a much cheaper option but still requires installing a complete operating system—a bit of a waste as well for most use cases.

- Next in line is containerization, with the likes of Docker and Kubernetes. These can be very powerful and are a good alternative.

Still, there are many cases when we’re just creating small projects or one-off scripts. Or perhaps you just don’t want to containerize your application. It’s another thing you need to learn and understand, after all. Whatever the reason is, virtual environments are a great way to isolate your project’s dependencies.

There are several ways to create a Python virtual environment, depending on the Python version you are running.

Before you read on, I want to point you to two other tools, Python Poetry and Pipenv. Both these tools combine the functionality of tools you are about to learn: virtualenv and pip. On top of that, they add several extras, most notably their ability to do proper dependency resolution.

To better understand virtual environments, I recommend you learn the basics first though, using this article. I just want to ensure that you know there are nicer ways to manage your packages, dependencies, and virtual environments.

Python 3.4 and above

If you are running Python 3.4+, you can use the venv module baked into Python:

python -m venv <directory>

This command creates a venv in the specified directory and copies pip into it as well. If you’re unsure what to call the directory: venv is a commonly seen option; it doesn’t leave anyone guessing what it is. So the command, in that case, would become:

python -m venv venv

A little further in this article, we’ll look closely at the just-created directory. But let’s first look at how to activate this virtual environment.

All other Python versions

The alternative that works for any Python version is using the virtualenv package. You may need to install it first with pip install:

pip install virtualenv

Once installed, you can create a virtual environment with:

virtualenv [directory]

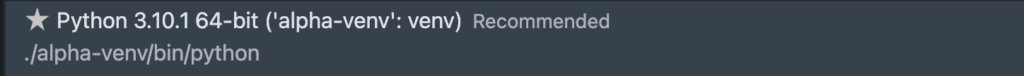

Python venv activation

How you activate your virtual environment depends on the OS you’re using.

Windows venv activation

To activate your venv on Windows, you need to run a script that gets installed by venv. If you created your venv in a directory called myenv, the command would be:

# In cmd.exe venvScriptsactivate.bat # In PowerShell venvScriptsActivate.ps1

Linux and MacOS venv activation

On Linux and MacOS, we activate our virtual environment with the source command. If you created your venv in the myvenv directory, the command would be:

$ source myvenv/bin/activate

That’s it! We’re ready to rock! You can now install packages with pip, but I advise you to keep reading to understand the venv better first.

Modules, Packages, And Virtual Environments

My course Python Fundamentals II extensively covers:

- creating modules and packages

- Using virtual environments

- Leveraging Python package managers like Poetry and Pipenv to make your life as a programmer easier.

Advance your productivity as a Python programmer and join my course today!

How a Python venv works

When you activate a virtual environment, your PATH variable is changed. On Linux and MacOS, you can see it for yourself by printing the path with echo $PATH. On Windows, use echo %PATH% (in cmd.exe) or $Env:Path (in PowerShell). In my case, on Windows, it looks like this:

C:UserserikDevvenvScripts;C:Program FilesPowerShell7;C:Program FilesAdoptOpen....

It’s a big list, and I only showed the beginning of it. As you can see, the Scripts directory of my venv is put in front of everything else, effectively overriding all the system-wide Python software.

So what does this PATH variable do?

When you enter a command that can’t be found in the current working directory, your OS starts looking at all the paths in the PATH variable. It’s the same for Python. When you import a library, Python starts looking in your PATH for library locations. And that’s where our venv-magic happens: if your venv is there in front of all the other paths, the OS will look there first before looking at system-wide directories like /usr/bin. Hence, anything that gets installed in our venv is found first, and that’s how we can override system-wide packages and tools.

What’s inside a venv?

If you take a look inside the directory of your venv, you’ll see something like this on Windows:

.

├── Include

├── Lib

│ └── site-packages

├── pyvenv.cfg

└── Scripts

├── activate

├── activate.bat

├── Activate.ps1

├── deactivate.bat

├── pip3.10.exe

├── pip3.exe

├── pip.exe

├── python.exe

└── pythonw.exe

And on Linux and MacOS:

You can see that:

- The Python command is made available as both python and python3 (on Linux and MacOS), and the version is pinned to the version with which you created the venv by creating a symlink to it.

- On Windows, the Python binary is copied over to the scripts directory.

- All packages you install end up in the site-packages directory.

- We have activation scripts for multiple shell types (bash, csh, fish, PowerShell)

- Pip is available under pip and pip3, and even more specifically under the name

pip3.7because I had a Python 3.7 installation at the time of writing this.

Deactivate the Python venv

Once you have finished working on your project, it’s a good habit to deactivate its venv. By deactivating, you leave the virtual environment. Without deactivating your venv, all other Python code you execute, even if it is outside your project directory, will also run inside the venv.

Luckily, deactivating your virtual environment couldn’t be simpler. Just enter this: deactivate. It works the same on all operating systems.

Deleting a Python venv

You can completely remove a virtual environment, but how you do that depends on what you used to create the venv. Let’s look at the most common options.

Delete a venv created with Virtualenv or python -m venv

There’s no special command to delete a virtual environment if you used virtualenv or python -m venv to create your virtual environment, as is demonstrated in this article. When creating the virtualenv, you gave it a directory to create this environment in.

If you want to delete this virtualenv, deactivate it first and then remove the directory with all its content. On Unix-like systems and in Windows Powershell, you would do something like this:

deactivate # If your virtual environment is in a directory called 'venv': rm -r venv

Delete a venv with Pipenv

If you used Pipenv to create the venv, it’s a lot easier. You can use the following command to delete the current venv:

pipenv --rm

Make sure you are inside the project directory. In other words, the directory where the Pipenv and Pipenv.lock files reside. This way, pipenv knows which virtual environment it has to delete.

If this doesn’t work, you can get a little nastier and manually remove the venv. First, ask pipenv where the actual virtualenv is located with the following command:

pipenv --env /home/username/.local/share/virtualenvs/yourproject-IogVUtsM

It will output the path to the virtual environment and all of its files and look similar to the example above. The next step is to remove that entire directory, and you’re done.

Delete a venv with Poetry

If you created the virtualenv with Poetry, you can list the available venvs with the following command:

poetry env list

You’ll get a list like this:

test-O3eWbxRl-py2.7 test-O3eWbxRl-py3.6 test-O3eWbxRl-py3.7 (Activated)

You can remove the environment you want with the poetry env remove command. You need to specify the exact name from the output above, for example:

poetry env remove test-O3eWbxRl-py3.7

Conclusion

You learned how to create, activate, deactivate, and delete virtual environments. We also looked behind the curtains to see why and how a venv works. Now that you know how to create a venv, you need to learn how to install packages inside of it. After that, I strongly recommend you to learn about Pipenv or Poetry. These tools combine the management of your virtual environment with proper package and dependency management.

Keep learning

- Next up: how to install packages with pip inside your venv

- Pipenv is a better way of managing your venv and packages.

- Learn the most common Linux commands (like cd, mkdir, pwd, etcetera)

- Official venv documentation: If you want to know all the details and command-line options

Are you enjoying this free tutorial? Please also have a look at my premium courses. They offer a superior user experience with small, easy-to-digest lessons and topics, progress tracking, quizzes to test your knowledge, and practice sessions. Each course will earn you a downloadable course certificate.

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Working With Python Virtual Environments

In this tutorial, you’ll learn how to work with Python’s venv module to create and manage separate virtual environments for your Python projects. Each environment can use different versions of package dependencies and Python. After you’ve learned to work with virtual environments, you’ll know how to help other programmers reproduce your development setup, and you’ll make sure that your projects never cause dependency conflicts for one another.

By the end of this tutorial, you’ll know how to:

- Create and activate a Python virtual environment

- Explain why you want to isolate external dependencies

- Visualize what Python does when you create a virtual environment

- Customize your virtual environments using optional arguments to

venv - Deactivate and remove virtual environments

- Choose additional tools for managing your Python versions and virtual environments

Virtual environments are a common and effective technique used in Python development. Gaining a better understanding of how they work, why you need them, and what you can do with them will help you master your Python programming workflow.

Throughout the tutorial, you can select code examples for either Windows, Ubuntu Linux, or macOS. Pick your platform at the top right of the relevant code blocks to get the commands that you need, and feel free to switch between your options if you want to learn how to work with Python virtual environments on other operating systems.

How Can You Work With a Python Virtual Environment?

If you just need to get a Python virtual environment up and running to continue working on your favorite project,

then this section is the right place for you.

The instructions in this tutorial use Python’s venv module to create virtual environments.

This module is part of Python’s standard library, and it’s the officially recommended way to create virtual environments since Python 3.5.

For basic usage, venv is an excellent choice because it already comes packaged with your Python installation. With that in mind, you’re ready to create your first virtual environment in this tutorial.

Create It

Any time you’re working on a Python project that uses external dependencies that you’re installing with pip,

it’s best to first create a virtual environment:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

If you’re using Python on Windows

and you haven’t configured the PATH and PATHEXT variables,

then you might need to provide the full path to your Python executable:

PS> C:UsersNameAppDataLocalProgramsPythonPython310python -m venv venv

The system path shown above assumes that you installed Python 3.10 using the Windows installer provided by the Python downloads page. The path to the Python executable on your system might be different. Working with PowerShell, you can find the path using the where.exe python command.

Many Linux operating systems ship with a version of Python 3.

If python3 doesn’t work, then you’ll have to first install Python, and you may need to use the specific name of the executable version that you installed, for example python3.10 for Python 3.10.x. If that’s the case for you, remember to replace mentions of python3 in the code blocks with your specific version number.

Older versions of macOS come with a system installation of Python 2.7.x that you should never use to run your scripts. If you’re working on macOS < 12.3 and invoke the Python interpreter with python instead of python3, then

you might accidentally start up the outdated system Python interpreter.

If running python3 doesn’t work, then you’ll have to first install a modern version of Python.

Activate It

Great! Now your project has its own virtual environment. Generally, before you start using it, you’ll first activate the environment by executing a script that comes with the installation:

- Windows

- Linux + macOS

PS> venvScriptsactivate

(venv) PS>

$ source venv/bin/activate

(venv) $

Before you run this command, make sure that you’re in the folder that contains the virtual environment you just created.

Once you can see the name of your virtual environment—in this case (venv)—in your command prompt, then you know that your virtual environment is active. You’re all set and ready to install your external packages!

Install Packages Into It

After creating and activating your virtual environment, you can now install any external dependencies that you need for your project:

- Windows

- Linux + macOS

(venv) PS> python -m pip install <package-name>

(venv) $ python -m pip install <package-name>

This command is the default command that you should use to install external Python packages with pip. Because you first created and activated the virtual environment, pip will install the packages in an isolated location.

Congratulations, you can now install your packages to your virtual environment. To get to this point, you began by creating a Python virtual environment named venv and then activated it in your current shell session.

As long as you don’t close your terminal, every Python package that you’ll install will end up in this isolated environment instead of your global Python site-packages. That means you can now work on your Python project without worrying about dependency conflicts.

Deactivate It

Once you’re done working with this virtual environment, you can deactivate it:

- Windows

- Linux + macOS

(venv) PS> deactivate

PS>

After executing the deactivate command, your command prompt returns to normal.

This change means that you’ve exited your virtual environment. If you interact with Python or pip now, you’ll interact with your globally configured Python environment.

If you want to go back into a virtual environment that you’ve created before, you again need to run the activate script of that virtual environment.

At this point, you’ve covered the essentials of working with Python virtual environments.

If that’s all you need, then happy trails as you continue creating!

However, if you want to know what exactly just happened,

why so many tutorials ask you to create a virtual environment in the first place,

and what a Python virtual environment really is,

then keep on reading! You’re about to go deep!

Why Do You Need Virtual Environments?

Nearly everyone in the Python community suggests that you use virtual environments for all your projects.

But why?

If you want to find out why you need to set up a Python virtual environment in the first place,

then this is the right section for you.

The short answer is that Python isn’t great at dependency management.

If you’re not specific,

then pip will place all the external packages that you install in a folder called site-packages/ in your base Python installation.

Technically, Python comes with two site-packages folders:

purelib/should contain only modules written in pure Python code.platlib/should contain binaries that aren’t written in pure Python, for example.dll,.so, or.pydistfiles.

You can find these folders in different locations if you’re working on Fedora or RedHat Linux distributions.

However, most operating systems implement Python’s site-packages setting so that both locations point to the same path, effectively creating a single site-packages folder.

You can check the paths using sysconfig:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

>>>

>>> import sysconfig

>>> sysconfig.get_path("purelib")

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310\Lib\site-packages'

>>> sysconfig.get_path("platlib")

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310\Lib\site-packages'

>>>

>>> import sysconfig

>>> sysconfig.get_path("purelib")

'/home/name/path/to/venv/lib/python3.10/site-packages'

>>> sysconfig.get_path("platlib")

'/home/name/path/to/venv/lib/python3.10/site-packages'

>>>

>>> import sysconfig

>>> sysconfig.get_path("purelib")

'/Users/name/path/to/venv/lib/python3.10/site-packages'

>>> sysconfig.get_path("platlib")

'/Users/name/path/to/venv/lib/python3.10/site-packages'

Most likely, both outputs will show you the same path. If both outputs are the same, then your operating system doesn’t put purelib modules into a different folder than platlib modules. If two different paths show up, then your operating system makes this distinction.

Even if your operating system distinguishes between the two, dependency conflicts will still arise because all purelib modules will go into a single location for purelib modules, and the same will happen with the platlib modules.

To work with virtual environments, you don’t need to worry about the implementation detail of a single site-packages folder or two separate ones. In fact, you probably won’t ever need to think about it again. If you want to, however, you can keep in mind that when someone mentions Python’s site-packages directory, they could be talking about two different directories.

Several issues can come up if all of your external packages land in the same folder. In this section, you’ll learn more about them, as well as other problems that virtual environments mitigate.

Avoid System Pollution

Linux and macOS come preinstalled with a version of Python that the operating system uses for internal tasks.

If you install packages to your operating system’s global Python, these packages will mix with the system-relevant packages. This mix-up could have unexpected side effects on tasks crucial to your operating system’s normal behavior.

Additionally, if you update your operating system, then the packages you installed might get overwritten and lost. You don’t want either of those headaches to happen!

Sidestep Dependency Conflicts

One of your projects might require a different version of an external library than another one. If you have only one place to install packages, then you can’t work with two different versions of the same library. This is one of the most common reasons for the recommendation to use a Python virtual environment.

To better understand why this is so important, imagine you’re building Django websites for two different clients. One client is comfortable with their existing web app, which you initially built using Django 2.2.26, and that client refuses to update their project to a modern Django version. Another client wants you to include async functionality in their website, which is only available starting from Django 4.0.

If you installed Django globally, you could only have one of the two versions installed:

- Windows

- Linux + macOS

PS> python -m pip install django==2.2.26

PS> python -m pip list

Package Version

---------- -------

Django 2.2.26

pip 22.0.4

pytz 2022.1

setuptools 58.1.0

sqlparse 0.4.2

PS> python -m pip install django==4.0.3

PS> python -m pip list

Package Version

---------- -------

asgiref 3.5.0

Django 4.0.3

pip 22.0.4

pytz 2022.1

setuptools 58.1.0

sqlparse 0.4.2

tzdata 2022.1

$ python3 -m pip install django==2.2.26

$ python3 -m pip list

Package Version

---------- -------

Django 2.2.26

pip 22.0.4

pytz 2022.1

setuptools 58.1.0

sqlparse 0.4.2

$ python3 -m pip install django==4.0.3

$ python3 -m pip list

Package Version

---------- -------

asgiref 3.5.0

Django 4.0.3

pip 22.0.4

pytz 2022.1

setuptools 58.1.0

sqlparse 0.4.2

If you install two different versions of the same package into your global Python environment, the second installation overwrites the first one. For the same reason, having a single virtual environment for both clients won’t work either. You can’t have two different versions of the same package in a single Python environment.

Looks like you won’t be able to work on one of the two projects with this setup! However, if you create a virtual environment for each of your clients’ projects, then you can install a different version of Django into each of them:

- Windows

- Linux + macOS

PS> mkdir client-old

PS> cd client-old

PS> python -m venv venv --prompt="client-old"

PS> venvScriptsactivate

(client-old) PS> python -m pip install django==2.2.26

(client-old) PS> python -m pip list

Package Version

---------- -------

Django 2.2.26

pip 22.0.4

pytz 2022.1

setuptools 58.1.0

sqlparse 0.4.2

(client-old) PS> deactivate

PS> cd ..

PS> mkdir client-new

PS> cd client-new

PS> python -m venv venv --prompt="client-new"

PS> venvScriptsactivate

(client-new) PS> python -m pip install django==4.0.3

(client-new) PS> python -m pip list

Package Version

---------- -------

asgiref 3.5.0

Django 4.0.3

pip 22.0.4

setuptools 58.1.0

sqlparse 0.4.2

tzdata 2022.1

(client-new) PS> deactivate

$ mkdir client-old

$ cd client-old

$ python3 -m venv venv --prompt="client-old"

$ source venv/bin/activate

(client-old) $ python -m pip install django==2.2.26

(client-old) $ python -m pip list

Package Version

---------- -------

Django 2.2.26

pip 22.0.4

pytz 2022.1

setuptools 58.1.0

sqlparse 0.4.2

(client-old) $ deactivate

$ cd ..

$ mkdir client-new

$ cd client-new

$ python3 -m venv venv --prompt="client-new"

$ source venv/bin/activate

(client-new) $ python -m pip install django==4.0.3

(client-new) $ python -m pip list

Package Version

---------- -------

asgiref 3.5.0

Django 4.0.3

pip 22.0.4

setuptools 58.1.0

sqlparse 0.4.2

(client-new) $ deactivate

If you now activate either of the two virtual environments, then you’ll notice that it still holds its own specific version of Django. The two environments also have different dependencies, and each only contains the dependencies necessary for that version of Django.

With this setup, you can activate one environment when you work on one project and another when you work on another. Now you can keep any number of clients happy at the same time!

Minimize Reproducibility Issues

If all your packages live in one location, then it’ll be difficult to only pin dependencies that are relevant for a single project.

If you’ve worked with Python for a while, then your global Python environment might already include all sorts of third-party packages. If that’s not the case, then pat yourself on the back! You’ve probably installed a new version of Python recently, or you already know how to handle virtual environments to avoid system pollution.

To clarify what reproducibility issues you can encounter when sharing a Python environment across multiple projects, you’ll look into an example situation next. Imagine you’ve worked on two independent projects over the past month:

- A web scraping project with Beautiful Soup

- A Flask application

Unaware of virtual environments, you installed all necessary packages into your global Python environment:

- Windows

- Linux + macOS

PS> python -m pip install beautifulsoup4 requests

PS> python -m pip install flask

$ python3 -m pip install beautifulsoup4 requests

$ python3 -m pip install flask

Your Flask app has turned out to be quite helpful, so other developers want to work on it as well. They need to reproduce the environment that you used for working on it. You want to go ahead and pin your dependencies so that you can share your project online:

- Windows

- Linux + macOS

PS> python -m pip freeze

beautifulsoup4==4.10.0

certifi==2021.10.8

charset-normalizer==2.0.12

click==8.0.4

colorama==0.4.4

Flask==2.0.3

idna==3.3

itsdangerous==2.1.1

Jinja2==3.0.3

MarkupSafe==2.1.1

requests==2.27.1

soupsieve==2.3.1

urllib3==1.26.9

Werkzeug==2.0.3

$ python3 -m pip freeze

beautifulsoup4==4.10.0

certifi==2021.10.8

charset-normalizer==2.0.12

click==8.0.4

Flask==2.0.3

idna==3.3

itsdangerous==2.1.1

Jinja2==3.0.3

MarkupSafe==2.1.1

requests==2.27.1

soupsieve==2.3.1

urllib3==1.26.9

Werkzeug==2.0.3

Which of these packages are relevant for your Flask app, and which ones are here because of your web scraping project? It’s hard to tell when all external dependencies live in a single bucket.

With a single environment like this one, you’d have to manually go through the dependencies and know which are necessary for your project and which aren’t. At best, this approach is tedious, but more likely, it’s error prone.

If you use a separate virtual environment for each of your projects, then it’ll be more straightforward to read the project requirements from your pinned dependencies. That means you can share your success when you develop a great app, making it possible for others to collaborate with you!

Dodge Installation Privilege Lockouts

Finally, you may need administrator privileges on a computer to install packages into the host Python’s site-packages directory. In a corporate work environment, you most likely won’t have that level of access to the machine that you’re working on.

If you use virtual environments, then you create a new installation location within the scope of your user privileges, which allows you to install and work with external packages.

Whether you’re coding as a hobby on your own machine, developing websites for clients, or working in a corporate environment, using a virtual environment will save you lots of grief in the long run.

What Is a Python Virtual Environment?

At this point, you’re convinced that you want to work with virtual environments.

Great, but what are you working with when you use a virtual environment?

If you want to understand what Python virtual environments are, then this is the right section for you.

The short answer is that a Python virtual environment is a folder structure

that gives you everything you need to run a lightweight yet isolated Python environment.

A Folder Structure

When you create a new virtual environment using the venv module, Python creates a self-contained folder structure and copies or symlinks the Python executable files into that folder structure.

You don’t need to dig deeply into this folder structure to learn more about what virtual environments are made of. In just a bit, you’ll carefully scrape off the topsoil and investigate the high-level structures that you uncover.

However, if you’ve already got your shovel ready and you’re itching to dig, then open the collapsible section below:

Welcome, brave one. You’ve accepted the challenge to venture deeper into your virtual environment’s folder structure! In this collapsible section, you’ll find instructions on how to take a look into that dark abyss.

On your command line, navigate to the folder that contains your virtual environment. Take a deep breath and brace yourself, then execute the tree command to display all the contents of the directory:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

You may need to first install tree, for example with sudo apt install tree.

The tree command displays the content of your venv directory in a very long tree structure.

However you end up displaying all the contents of the venv/ folder, you might be surprised what you find. Many developers experience a slight shock when they first take a peek. There are a lot of files in there!

If this was your first time and you felt that way, then welcome to the group of people who have taken a look and gotten overwhelmed.

A virtual environment folder contains a lot of files and folders, but you might notice that most of what makes this tree structure so long rests inside the site-packages/ folder. If you trim down the subfolders and files in there, you end up with a tree structure that isn’t too overwhelming:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

venv

│

├── Include

│

├── Lib

│ │

│ └── site-packages

│ │

│ ├── _distutils_hack

│ │

│ ├── pip

│ │

│ ├── pip-22.0.4.dist-info

│ │

│ ├── pkg_resources

│ │

│ ├── setuptools

│ │

│ ├── setuptools-58.1.0.dist-info

│ │

│ └── distutils-precedence.pth

│

│

├── Scripts

│ ├── Activate.ps1

│ ├── activate

│ ├── activate.bat

│ ├── deactivate.bat

│ ├── pip.exe

│ ├── pip3.10.exe

│ ├── pip3.exe

│ ├── python.exe

│ └── pythonw.exe

│

└── pyvenv.cfg

venv/

│

├── bin/

│ ├── Activate.ps1

│ ├── activate

│ ├── activate.csh

│ ├── activate.fish

│ ├── pip

│ ├── pip3

│ ├── pip3.10

│ ├── python

│ ├── python3

│ └── python3.10

│

├── include/

│

├── lib/

│ │

│ └── python3.10/

│ │

│ └── site-packages/

│ │

│ ├── _distutils_hack/

│ │

│ ├── pip/

│ │

│ ├── pip-22.0.4.dist-info/

│ │

│ ├── pkg_resources/

│ │

│ ├── setuptools/

│ │

│ ├── setuptools-58.1.0.dist-info/

│ │

│ └── distutils-precedence.pth

│

├── lib64/

│ │

│ └── python3.10/

│ │

│ └── site-packages/

│ │

│ ├── _distutils_hack/

│ │

│ ├── pip/

│ │

│ ├── pip-22.0.4.dist-info/

│ │

│ ├── pkg_resources/

│ │

│ ├── setuptools/

│ │

│ ├── setuptools-58.1.0.dist-info/

│ │

│ └── distutils-precedence.pth

│

└── pyvenv.cfg

venv/

│

├── bin/

│ ├── Activate.ps1

│ ├── activate

│ ├── activate.csh

│ ├── activate.fish

│ ├── pip

│ ├── pip3

│ ├── pip3.10

│ ├── python

│ ├── python3

│ └── python3.10

│

├── include/

│

├── lib/

│ │

│ └── python3.10/

│ │

│ └── site-packages/

│ │

│ ├── _distutils_hack/

│ │

│ ├── pip/

│ │

│ ├── pip-22.0.4.dist-ino/

│ │

│ ├── pkg_resources/

│ │

│ ├── setuptools/

│ │

│ ├── setuptools-58.1.0.dist-info/

│ │

│ └── distutils-precedence.pth

│

└── pyvenv.cfg

This reduced tree structure gives you a better overview of what’s going on in your virtual environment folder:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

-

Includeis an initially empty folder that Python uses to include C header files for packages you might install that depend on C extensions. -

Libcontains thesite-packagesfolder, which is one of the main reasons for creating your virtual environment. This folder is where you’ll install external packages that you want to use within your virtual environment. By default, your virtual environment comes preinstalled with two dependencies,pipand setuptools. You’ll learn more about them in a bit. -

Scriptscontains the executable files of your virtual environment. Most notable are the Python interpreter (python.exe), thepipexecutable (pip.exe), and the activation script for your virtual environment, which comes in a couple of different flavors to allow you to work with different shells. In this tutorial, you’ve usedactivate, which handles the activation of your virtual environment for Windows across most shells. -

pyvenv.cfgis a crucial file for your virtual environment. It contains only a couple of key-value pairs that Python uses to set variables in thesysmodule that determine which Python interpreter and which site-packages directory the current Python session will use. You’ll learn more about the settings in this file when you read about how a virtual environment works.

-

bin/contains the executable files of your virtual environment. Most notable are the Python interpreter (python) and thepipexecutable (pip), as well as their respective symlinks (python3,python3.10,pip3,pip3.10). The folder also contains activation scripts for your virtual environment. Your specific activation script depends on what shell you use. For example, in this tutorial, you ranactivate, which works for the Bash and Zsh shells. -

include/is an initially empty folder that Python uses to include C header files for packages you might install that depend on C extensions. -

lib/contains thesite-packages/directory nested in a folder that designates the Python version (python3.10/).site-packages/is one of the main reasons for creating your virtual environment. This folder is where you’ll install external packages that you want to use within your virtual environment. By default, your virtual environment comes preinstalled with two dependencies,pipand setuptools. You’ll learn more about them in a bit. -

lib64/in many Linux systems comes as a symlink tolib/for compatibility reasons. Some Linux systems may use the distinction betweenlib/andlib64/to install different versions of libraries depending on their architecture. -

pyvenv.cfgis a crucial file for your virtual environment. It contains only a couple of key-value pairs that Python uses to set variables in thesysmodule that determine which Python interpreter and which site-packages directory the current Python session will use. You’ll learn more about the settings in this file when you read about how a virtual environment works.

-

bin/contains the executable files of your virtual environment. Most notable are the Python interpreter (python) and thepipexecutable (pip), as well as their respective symlinks (python3,python3.10,pip3,pip3.10). The folder also contains activation scripts for your virtual environment. Your specific activation script depends on what shell you use. For example, in this tutorial, you ranactivate, which works for the Bash and Zsh shells. -

include/is an initially empty folder that Python uses to include C header files for packages you might install that depend on C extensions. -

lib/contains thesite-packages/directory nested in a folder that designates the Python version (python3.10/).site-packages/is one of the main reasons for creating your virtual environment. This folder is where you’ll install external packages that you want to use within your virtual environment. By default, your virtual environment comes preinstalled with two dependencies,pipand setuptools. You’ll learn more about them in a bit. -

pyvenv.cfgis a crucial file for your virtual environment. It contains only a couple of key-value pairs that Python uses to set variables in thesysmodule that determine which Python interpreter and which site-packages directory the current Python session will use. You’ll learn more about the settings in this file when you read about how a virtual environment works.

From this bird’s-eye view of the contents of your virtual environment folder, you can zoom out even further to discover that there are three essential parts of a Python virtual environment:

- A copy or a symlink of the Python binary

- A

pyvenv.cfgfile - A site-packages directory

The installed packages inside site-packages/ are optional but come as a reasonable default. However, your virtual environment would still be a valid virtual environment if this directory were empty, and there are ways to create it without installing any dependencies.

With the default settings, venv will install both pip and setuptools. Using pip is the recommended way to install packages in Python, and setuptools is a dependency for pip. Because installing other packages is the most common use case for Python virtual environments, you’ll want to have access to pip.

You can double-check that Python installed both pip and setuptools into your virtual environment by using pip list:

- Windows

- Linux + macOS

(venv) PS> python -m pip list

Package Version

---------- -------

pip 22.0.4

setuptools 58.1.0

(venv) $ python -m pip list

Package Version

---------- -------

pip 22.0.4

setuptools 58.1.0

Your version numbers may differ, but this output confirms that Python installed both packages when you created the virtual environment with its default settings.

These two installed packages make up most of the content of your new virtual environment. However, you’ll notice that there are also a couple of other folders in the site-packages/ directory:

-

The

_distutils_hack/module, in a manner true to its name, ensures that when performing package installations, Python picks the local._distutilssubmodule of setuptools over the standard library’sdistutilsmodule. -

The

pkg_resources/module helps applications discover plugins automatically and allows Python packages to access their resource files. It’s distributed together withsetuptools. -

The

{name}-{version}.dist-info/directories forpipand setuptools contain package distribution information that exists to record information about installed packages.

Finally, there’s also a file named distutils-precedence.pth. This file helps set the path precedence for distutils imports and works together with _distutils_hack to ensure that Python prefers the version of distutils that comes bundled with setuptools over the built-in one.

At this point, you’ve seen all the files and folders that make up a Python virtual environment if you’ve installed it using the built-in venv module.

Keep in mind that your virtual environment is just a folder structure, which means that you can delete and re-create it anytime you want to. But why this specific folder structure, and what does it make possible?

An Isolated Python Installation

Python virtual environments aim to provide a lightweight, isolated Python environment that you can quickly create and then discard when you don’t need it anymore. The folder structure that you’ve seen above makes that possible by providing three key pieces:

- A copy or a symlink of the Python binary

- A

pyvenv.cfgfile - A site-packages directory

You want to achieve an isolated environment so that any external packages you install won’t conflict with global site-packages. What venv does to make this possible is to reproduce the folder structure that a standard Python installation creates.

This structure accounts for the location of the copy or symlink of the Python binary and the site-packages directory, where Python installs external packages.

In addition to the Python binary and the site-packages directory, you get the pyvenv.cfg file. It’s a small file that contains only a couple of key-value pairs. However, these settings are crucial for making your virtual environment work:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

home = C:UsersNameAppDataLocalProgramsPythonPython310

include-system-site-packages = false

version = 3.10.3

home = /usr/local/bin

include-system-site-packages = false

version = 3.10.3

home = /Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10/bin

include-system-site-packages = false

version = 3.10.3

You’ll learn more about this file in a later section when reading about how a virtual environment works.

Suppose you closely inspect your newly minted virtual environment’s folder structure. In that case, you might notice that this lightweight installation doesn’t contain any of the trusted standard library modules. Some might say that Python without its standard library is like a toy car without batteries!

However, if you start the Python interpreter from within your virtual environment, then you can still access all the goodies from the standard library:

>>>

>>> import urllib

>>> from pprint import pp

>>> pp(dir(urllib))

['__builtins__',

'__cached__',

'__doc__',

'__file__',

'__loader__',

'__name__',

'__package__',

'__path__',

'__spec__']

In the example code snippet above, you’ve successfully imported both the urllib module and the pp() shortcut from the pretty print module. Then you used dir() to inspect the urllib module.

Both modules are part of the standard library, so how come you have access to them even though they’re not in the folder structure of your Python virtual environment?

You can access Python’s standard library modules because your virtual environment reuses Python’s built-ins and the standard library modules from the Python installation from which you created your virtual environment. In a later section, you’ll learn how the virtual environment achieves linking to your base Python’s standard library.

In addition to the standard library modules, you can optionally give your virtual environment access to the base installation’s site-packages through an argument when creating the environment:

- Windows

- Linux + macOS

PS C:> python -m venv venv --system-site-packages

$ python3 -m venv venv --system-site-packages

If you add --system-site-packages when you call venv, Python will set the value to include-system-site-packages in pyvenv.cfg to true. This setting means that you can use any external packages that you installed to your base Python as if you’d installed them into your virtual environment.

This connection works in only one direction. Even if you give your virtual environment access to the source Python’s site-packages folder, any new packages you install into your virtual environment won’t mingle with the packages there. Python will respect the isolated nature of installations to your virtual environment and place them into the separate site-packages directory within the virtual environment.

You know that a Python virtual environment is just a folder structure with a settings file. It might or might not come with pip preinstalled, and it has access to the source Python’s site-packages directory while remaining isolated. But you might wonder how all of this works.

How Does a Virtual Environment Work?

If you know what a Python virtual environment is but wonder how it manages to create the lightweight isolation it provides, then you’re in the right section. Here you’ll learn how the folder structure and the settings in your pyvenv.cfg file interact with Python to provide a reproducible and isolated space for installing external dependencies.

It Copies Structure and Files

When you create a virtual environment using venv, the module re-creates the file and folder structure of a standard Python installation on your operating system. Python also copies or symlinks into that folder structure the Python executable with which you’ve called venv:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

venv

│

├── Include

│

├── Lib

│ │

│ └── site-packages

│

├── Scripts

│ ├── Activate.ps1

│ ├── activate

│ ├── activate.bat

│ ├── deactivate.bat

│ ├── pip.exe

│ ├── pip3.10.exe

│ ├── pip3.exe

│ ├── python.exe

│ └── pythonw.exe

│

└── pyvenv.cfg

venv/

│

├── bin/

│ ├── Activate.ps1

│ ├── activate

│ ├── activate.csh

│ ├── activate.fish

│ ├── pip

│ ├── pip3

│ ├── pip3.10

│ ├── python

│ ├── python3

│ └── python3.10

│

├── include/

│

├── lib/

│ │

│ └── python3.10/

│ │

│ └── site-packages/

│

├── lib64/

│ │

│ └── python3.10/

│ │

│ └── site-packages/

│

└── pyvenv.cfg

venv/

│

├── bin/

│ ├── Activate.ps1

│ ├── activate

│ ├── activate.csh

│ ├── activate.fish

│ ├── pip

│ ├── pip3

│ ├── pip3.10

│ ├── python

│ ├── python3

│ └── python3.10

│

├── include/

│

├── lib/

│ │

│ └── python3.10/

│ │

│ └── site-packages/

│

└── pyvenv.cfg

If you locate your system-wide Python installation on your operating system and inspect the folder structure there, then you’ll see that your virtual environment resembles that structure.

You can find the base Python installation that your virtual environment is based on by navigating to the path you can find under the home key in pyvenv.cfg.

While you might find some additional files and folders in your base Python installation, you’ll notice that the standard folder structure is the same as in your virtual environment. venv creates this folder structure to assure that Python will work as expected in isolation, without the need to apply many additional changes.

It Adapts the Prefix-Finding Process

With the standard folder structure in place, the Python interpreter in your virtual environment can understand where all relevant files are located. It does this with only minor adaptations to its prefix-finding process according to the venv specification.

Instead of looking for the os module to determine the location of the standard library, the Python interpreter first looks for a pyvenv.cfg file. If the interpreter finds this file and it contains a home key, then the interpreter will use that key to set the value for two variables:

sys.base_prefixwill hold the path to the Python executable used to create this virtual environment, which you can find at the path defined under thehomekey inpyvenv.cfg.sys.prefixwill point to the directory containingpyvenv.cfg.

If the interpreter doesn’t find a pyvenv.cfg file, then it determines that it’s not running within a virtual environment, and both sys.base_prefix and sys.prefix will then point to the same path.

You can confirm that this works as described. Spin up a Python interpreter within an active virtual environment and inspect both variables:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

>>>

>>> import sys

>>> sys.prefix

'C:\Users\Name\path\to\venv'

>>> sys.base_prefix

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310'

>>>

>>> import sys

>>> sys.prefix

'/home/name/path/to/venv'

>>> sys.base_prefix

'/usr/local'

>>>

>>> import sys

>>> sys.prefix

'/Users/name/path/to/venv'

>>> sys.base_prefix

'/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10'

You can see that the variables point to different locations on your system.

Now go ahead and deactivate the virtual environment, enter a new interpreter session, and rerun the same code:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

>>>

>>> import sys

>>> sys.prefix

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310'

>>> sys.base_prefix

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310'

>>>

>>> import sys

>>> sys.prefix

'/usr/local'

>>> sys.base_prefix

'/usr/local'

>>>

>>> import sys

>>> sys.prefix

'/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10'

>>> sys.base_prefix

'/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10'

You should see that both sys.prefix and sys.base_prefix now point to the same path.

If these two variables have different values, then Python adapts where it’ll look for modules:

The

siteandsysconfigstandard-library modules are modified such that the standard library and header files are found relative tosys.base_prefix[…], while site-package directories […] are still found relative tosys.prefix[…]. (Source)

This change effectively allows the Python interpreter in your virtual environment to use the standard library modules from your base Python installation while pointing to its internal site-packages directory to install and access external packages.

It Links Back to Your Standard Library

Python virtual environments aim to be a lightweight way to provide you with an isolated Python environment that you can quickly create and then delete when you don’t need it anymore. To make this possible, venv copies only the minimally necessary files:

[A] Python virtual environment in its simplest form would consist of nothing more than a copy or symlink of the Python binary accompanied by a

pyvenv.cfgfile and a site-packages directory. (Source)

The Python executable in your virtual environment has access to the standard library modules of the Python installation on which you based the environment. Python makes this possible by pointing to the file path of the base Python executable in the home setting in pyvenv.cfg:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

home = C:UsersNameAppDataLocalProgramsPythonPython310

include-system-site-packages = false

version = 3.10.3

home = /usr/local/bin

include-system-site-packages = false

version = 3.10.3

home = /Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10/bin

include-system-site-packages = false

version = 3.10.3

If you navigate to the path value of the highlighted line in pyvenv.cfg and list the contents of the folder, then you find the base Python executable that you used to create your virtual environment. From there, you can navigate to find the folder that contains your standard library modules:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

PS> ls C:UsersNameAppDataLocalProgramsPythonPython310

Directory: C:UsersNameAppDataLocalProgramsPythonPython310

Mode LastWriteTime Length Name

---- ------------- ------ ----

d----- 12/19/2021 5:09 PM DLLs

d----- 12/19/2021 5:09 PM Doc

d----- 12/19/2021 5:09 PM include

d----- 12/19/2021 5:09 PM Lib

d----- 12/19/2021 5:09 PM libs

d----- 12/21/2021 2:04 PM Scripts

d----- 12/19/2021 5:09 PM tcl

d----- 12/19/2021 5:09 PM Tools

-a---- 12/7/2021 4:28 AM 32762 LICENSE.txt

-a---- 12/7/2021 4:29 AM 1225432 NEWS.txt

-a---- 12/7/2021 4:28 AM 98544 python.exe

-a---- 12/7/2021 4:28 AM 61680 python3.dll

-a---- 12/7/2021 4:28 AM 4471024 python310.dll

-a---- 12/7/2021 4:28 AM 97008 pythonw.exe

-a---- 12/7/2021 4:29 AM 97168 vcruntime140.dll

-a---- 12/7/2021 4:29 AM 37240 vcruntime140_1.dll

PS> ls C:UsersNameAppDataLocalProgramsPythonPython310Lib

Directory: C:UsersNameAppDataLocalProgramsPythonPython310Lib

Mode LastWriteTime Length Name

---- ------------- ------ ----

d----- 12/19/2021 5:09 PM asyncio

d----- 12/19/2021 5:09 PM collections

# ...

-a---- 12/7/2021 4:27 AM 5302 __future__.py

-a---- 12/7/2021 4:27 AM 65 __phello__.foo.py

$ ls /usr/local/bin

2to3-3.10 pip3.10 python3.10

idle3.10 pydoc3.10 python3.10-config

$ ls /usr/local/lib/python3.10

$ ls

abc.py hmac.py shelve.py

aifc.py html shlex.py

_aix_support.py http shutil.py

antigravity.py idlelib signal.py

# ...

graphlib.py runpy.py zipimport.py

gzip.py sched.py zoneinfo

hashlib.py secrets.py

heapq.py selectors.py

$ ls /Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10/bin

2to3 pip3.10 python3-intel64

2to3-3.10 pydoc3 python3.10

idle3 pydoc3.10 python3.10-config

idle3.10 python3 python3.10-intel64

pip3 python3-config

$ ls /Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10/lib/python3.10/

LICENSE.txt fnmatch.py rlcompleter.py

__future__.py fractions.py runpy.py

__phello__.foo.py ftplib.py sched.py

__pycache__ functools.py secrets.py

# ...

ensurepip quopri.py zipimport.py

enum.py random.py zoneinfo

filecmp.py re.py

fileinput.py reprlib.py

Python is set up to find these modules by adding the relevant path to sys.path. During initialization, Python automatically imports the site module, which sets the defaults for this argument.

The paths that your Python session has access to in sys.path determine which locations Python can import modules from.

If you activate your virtual environment and enter a Python interpreter, then you can confirm that the path to the standard library folder of your base Python installation is available:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

>>>

>>> import sys

>>> from pprint import pp

>>> pp(sys.path)

['',

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310\python310.zip',

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310\DLLs',

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310\lib',

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310',

'C:\Users\Name\path\to\venv',

'C:\Users\Name\path\to\venv\lib\site-packages']

>>>

>>> import sys

>>> from pprint import pp

>>> pp(sys.path)

['',

'/usr/local/lib/python310.zip',

'/usr/local/lib/python3.10',

'/usr/local/lib/python3.10/lib-dynload',

'/home/name/path/to/venv/lib/python3.10/site-packages']

>>>

>>> import sys

>>> from pprint import pp

>>> pp(sys.path)

['',

'/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10/lib/python310.zip',

'/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10/lib/python3.10',

'/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10/lib/python3.10/lib-dynload',

'/Users/name/path/to/venv/lib/python3.10/site-packages']

Because the path to the directory that contains your standard library modules is available in sys.path, you’ll be able to import any of them when you work with Python from within your virtual environment.

It Modifies Your PYTHONPATH

To assure that the scripts you want to run use the Python interpreter within your virtual environment, venv modifies the PYTHONPATH environment variable that you can access using sys.path.

If you inspect that variable without an active virtual environment, you’ll see the default path locations for your default Python installation:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

>>>

>>> import sys

>>> from pprint import pp

>>> pp(sys.path)

['',

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310\python310.zip',

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310\DLLs',

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310\lib',

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310',

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Roaming\Python\Python310\site-packages',

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310\lib\site-packages']

>>>

>>> import sys

>>> from pprint import pp

>>> pp(sys.path)

['',

'/usr/local/lib/python310.zip',

'/usr/local/lib/python3.10',

'/usr/local/lib/python3.10/lib-dynload',

'/usr/local/lib/python3.10/site-packages']

>>>

>>> import sys

>>> from pprint import pp

>>> pp(sys.path)

['',

'/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10/lib/python310.zip',

'/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10/lib/python3.10',

'/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10/lib/python3.10/lib-dynload',

'/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10/lib/python3.10/site-packages']

Note the highlighted lines, which represent the path to the site-packages directory. This folder contains external modules that you’d install, for example, using pip. Without an activated virtual environment, this directory is nested within the same folder structure as the Python executable.

However, if you activate your virtual environment before starting another interpreter session and rerun the same commands, then you’ll get different output:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

>>>

>>> import sys

>>> from pprint import pp

>>> pp(sys.path)

['',

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310\python310.zip',

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310\DLLs',

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310\lib',

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310',

'C:\Users\Name\path\to\venv',

'C:\Users\Name\path\to\venv\lib\site-packages']

>>>

>>> import sys

>>> from pprint import pp

>>> pp(sys.path)

['',

'/usr/local/lib/python310.zip',

'/usr/local/lib/python3.10',

'/usr/local/lib/python3.10/lib-dynload',

'/home/name/path/to/venv/lib/python3.10/site-packages']

>>>

>>> import sys

>>> from pprint import pp

>>> pp(sys.path)

['',

'/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10/lib/python310.zip',

'/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10/lib/python3.10',

'/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10/lib/python3.10/lib-dynload',

'/Users/name/path/to/venv/lib/python3.10/site-packages']

Python replaced the default site-packages directory path with the one that lives inside your virtual environment. This change means that Python will load any external packages installed in your virtual environment. Conversely, because the path to your base Python’s site-packages directory isn’t in this list anymore, Python won’t load modules from there.

This change in Python’s path settings effectively creates the isolation of external packages in your virtual environment.

Optionally, you can get read-only access to the system site-packages directory of your base Python installation by passing an argument when creating the virtual environment.

It Changes Your Shell PATH Variable on Activation

For convenience, you’ll usually activate your virtual environment before working in it, even though you don’t have to.

To activate your virtual environment, you need to execute an activation script:

- Windows

- Linux + macOS

PS> venvScriptsactivate

(venv) PS>

$ source venv/bin/activate

(venv) $

Which activation script you’ll have to run depends on your operating system and the shell that you’re using.

If you dig into your virtual environment’s folder structure, then you’ll find a few different activation scripts that it ships with:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

venv

│

├── Include

│

├── Lib

│

├── Scripts

│ ├── Activate.ps1

│ ├── activate

│ ├── activate.bat

│ ├── deactivate.bat

│ ├── pip.exe

│ ├── pip3.10.exe

│ ├── pip3.exe

│ ├── python.exe

│ └── pythonw.exe

│

└── pyvenv.cfg

venv/

│

├── bin/

│ ├── Activate.ps1

│ ├── activate

│ ├── activate.csh

│ ├── activate.fish

│ ├── pip

│ ├── pip3

│ ├── pip3.10

│ ├── python

│ ├── python3

│ └── python3.10

│

├── include/

│

├── lib/

│

├── lib64/

│

└── pyvenv.cfg

venv/

│

├── bin/

│ ├── Activate.ps1

│ ├── activate

│ ├── activate.csh

│ ├── activate.fish

│ ├── pip

│ ├── pip3

│ ├── pip3.10

│ ├── python

│ ├── python3

│ └── python3.10

│

├── include/

│

├── lib/

│

└── pyvenv.cfg

These activation scripts all have the same purpose. However, they need to provide different ways of achieving it because of the various operating systems and shells that users are working with.

Two critical actions happen in the activation script:

- Path: It sets the

VIRTUAL_ENVvariable to the root folder path of your virtual environment and prepends the relative location of its Python executable to yourPATH. - Command prompt: It changes the command prompt to the name that you passed when creating the virtual environment. It takes that name and puts it into parentheses, for example

(venv).

These changes put the convenience of virtual environments into effect within your shell:

- Path: Because the path to all the executables in your virtual environment now lives at the front of your

PATH, your shell will invoke the internal versions ofpipor Python when you just typepiporpython. - Command prompt: Because the script changed your command prompt, you’ll quickly know whether or not your virtual environment is activated.

Both of these changes are minor adaptations that exist purely for your convenience. They aren’t strictly necessary, but they make working with Python virtual environments more enjoyable.

You can inspect your PATH variable before and after activation of your virtual environment. If you’ve activated your virtual environment, then you’ll see the path to the folder containing your internal executables at the beginning of PATH:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

PS> $Env:Path

C:UsersNamepathtovenvScripts;C:Windowssystem32;C:Windows;C:WindowsSystem32Wbem;C:UsersNameAppDataLocalProgramsPythonPython310Scripts;C:UsersNameAppDataLocalProgramsPythonPython310;c:usersname.localbin;c:usersnameappdataroamingpythonpython310scripts

$ echo $PATH

/home/name/path/to/venv/bin:/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin:/home/name/.local/bin

$ echo $PATH

/Users/name/path/to/venv/bin:/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10/bin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/sbin:/sbin:/Users/name/.local/bin

Keep in mind that the output of printing your PATH variable will most likely look quite different. The important point is that the activation script has added the path to your virtual environment at the beginning of the PATH variable.

When you deactivate your virtual environment using deactivate, your shell reverses these changes and puts PATH and your command prompt back to the way they were before.

Give it a try and inspect the changes. This small change to your PATH variable gives you the convenience of running executables in your virtual environment without the need to provide the full path.

It Runs From Anywhere With Absolute Paths

You don’t need to activate your virtual environment to use it. You can work with your virtual environment without activating it, even though activating it is a common action that you’ll often see recommended.

If you provide only the name of an executable to your shell, it’ll look through the location recorded in PATH for an executable file sporting that name. It’ll then pick and run the first one that matches that criterion.

The activation script changes your PATH variable so that the binaries folder of your virtual environment is the first place your shell looks for executables. This change allows you to type only pip or python to run the respective programs situated inside your virtual environment.

If you don’t activate your virtual environment, then you can instead pass the absolute path of the Python executable inside your virtual environment to run any script from within your virtual environment:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

PS> C:UsersNamepathtovenvScriptspython.exe

$ /home/name/path/to/venv/bin/python

$ /Users/name/path/to/venv/bin/python

This command will start the Python interpreter within your virtual environment precisely the same way it would if you first activated the virtual environment and then called it with python.

How can you confirm that using the absolute path without activating the virtual environment starts the same interpreter as when you activate the virtual environment and run python?

Take some notes of possible ways to check, then try out some of the solutions mentioned in the Solution block below.

As described in previous sections of this tutorial, you could:

- Print

sys.pathand confirm that the site-packages directory within your virtual environment is listed - Confirm that

sys.prefixhas changed and now points to a folder in your virtual environment folder structure - Activate the virtual environment, then inspect the

PATHshell variable to find the path to your virtual environment’s binary executables listed in the first place

If you’re unsure why any of these approaches could confirm that this works as described, follow the links to the relevant sections in this tutorial to refresh your memory.

Alternatively, you could confirm which Python executable you’re using by starting the interpreter and running import sys; sys.executable. These commands will return the absolute path to your current Python interpreter. Does the path lead into your virtual environment folder structure?

You’ll often activate your virtual environment before working with it and deactivate it after you’re done. However, there is an everyday use case where using the absolute paths is a helpful approach.

Embedding the activation of your virtual environment in your script is a fussy exercise that goes wrong more often than it doesn’t. Instead, equipped with the knowledge that you’ve gained in this tutorial, you can use the absolute path to the Python interpreter in your virtual environment when running your script.

You could use this, for example, if you were setting up an hourly CRON job on your remote Linux server that checks for site connectivity asynchronously using the external aiohttp package that you installed in a virtual environment:

0 * * * *