Introduction

PIP is a package management system used to install and manage software packages written in Python. It stands for “preferred installer program” or “Pip Installs Packages.”

PIP for Python is a utility to manage PyPI package installations from the command line.

If you are using an older version of Python on Windows, you may need to install PIP. You can easily install PIP on Windows by downloading the installation package, opening the command line, and launching the installer.

This tutorial will show how to install PIP on Windows, check its version, upgrade, and configure.

Note: The latest versions of Python come with PIP pre-installed, but older versions require manual installation. The following guide is for version 3.4 and above. If you are using an older version of Python, you can upgrade Python via the Python website.

Prerequisites

- Computer running Windows or Windows server

- Access to the Command Prompt window

Before you start: Check if PIP is Already Installed

PIP is automatically installed with Python 2.7.9+ and Python 3.4+ and it comes with the virtualenv and pyvenv virtual environments.

Before you install PIP on Windows, check if PIP is already installed.

1. Launch the command prompt window:

- Press Windows Key + X.

- Click Run.

- Type in cmd.exe and hit enter.

Alternatively, type cmd in the Windows search bar and click the “Command Prompt” icon.

2. Type in the following command at the command prompt:

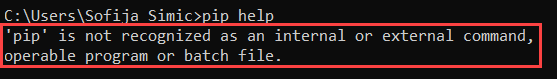

pip helpIf PIP responds, then PIP is installed. Otherwise, there will be an error saying the program could not be found.

Installing PIP On Windows

Follow the steps outlined below to install PIP on Windows.

Step 1: Download PIP get-pip.py

Before installing PIP, download the get-pip.py file.

1. Launch a command prompt if it isn’t already open. To do so, open the Windows search bar, type cmd and click on the icon.

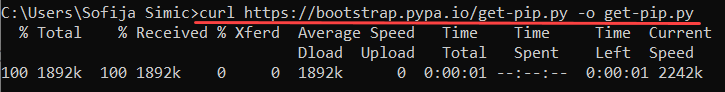

2. Then, run the following command to download the get-pip.py file:

curl https://bootstrap.pypa.io/get-pip.py -o get-pip.py

Step 2: Installing PIP on Windows

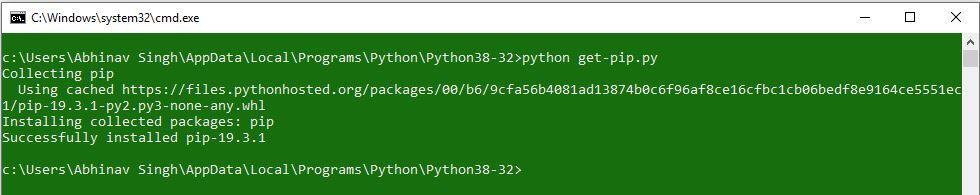

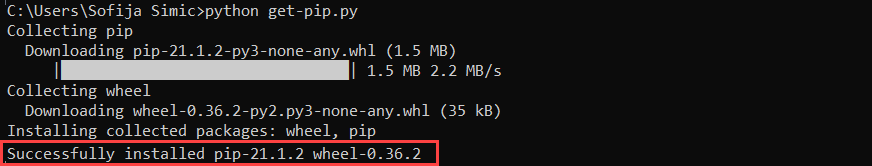

To install PIP type in the following:

python get-pip.py

If the file isn’t found, double-check the path to the folder where you saved the file. You can view the contents of your current directory using the following command:

dirThe dir command returns a full listing of the contents of a directory.

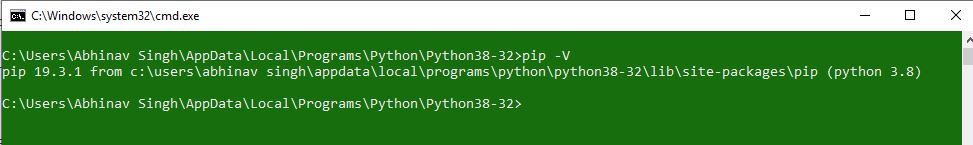

Step 3: Verify Installation

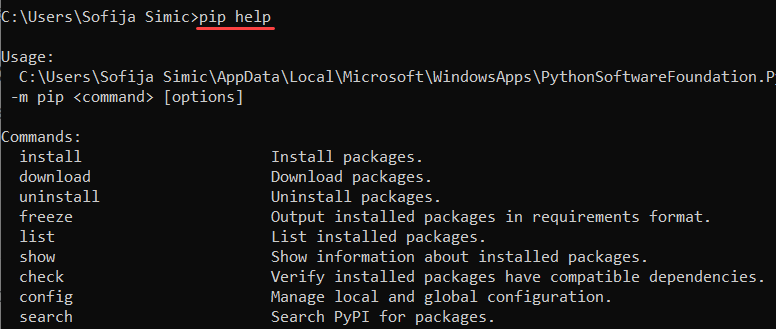

Once you’ve installed PIP, you can test whether the installation has been successful by typing the following:

pip helpIf PIP has been installed, the program runs, and you should see the location of the software package and a list of commands you can use with pip.

If you receive an error, repeat the installation process.

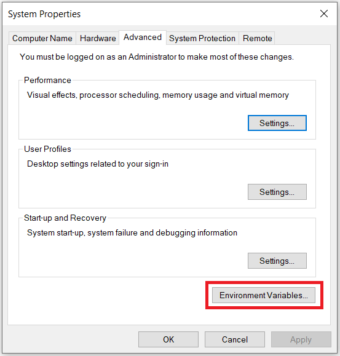

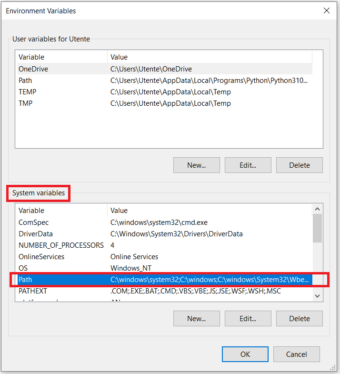

Step 4: Add Pip to Windows Environment Variables

To run PIP from any location, you need to add it to Windows environment variables to avoid getting the «not on PATH» error. To do so, follow the steps outlined below:

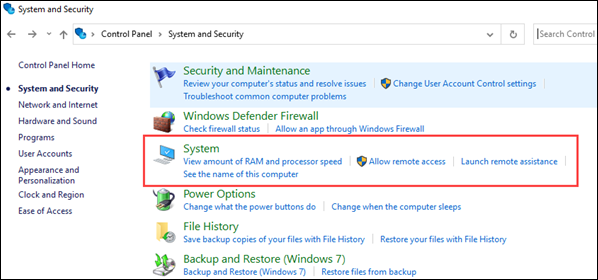

- Open the System and Security window by searching for it in the Control Plane.

- Navigate to System settings.

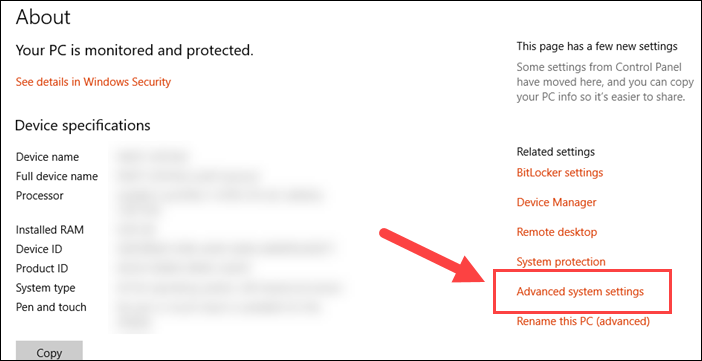

- Then, select Advanced system settings.

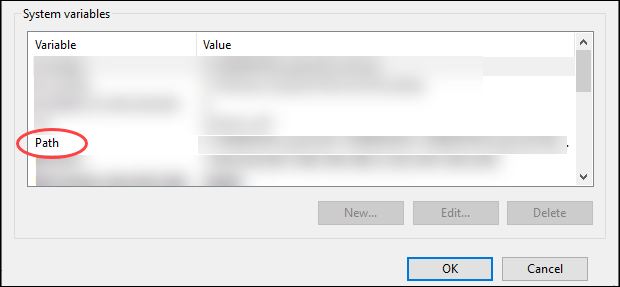

- Open the Environment Variables and double-click on the Path variable in the System Variables.

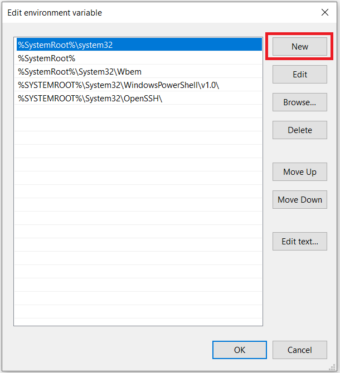

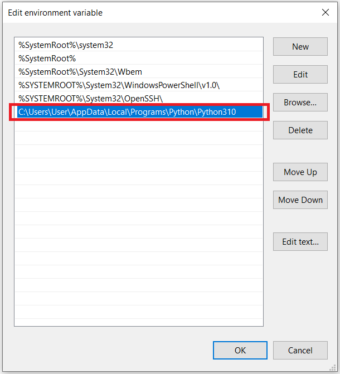

- Next, select New and add the directory where you installed PIP.

- Click OK to save the changes.

Step 5: Configuration

In Windows, the PIP configuration file is %HOME%pippip.ini.

There is also a legacy per-user configuration file. The file is located at %APPDATA%pippip.ini.

You can set a custom path location for this config file using the environment variable PIP_CONFIG_FILE.

Upgrading PIP for Python on Windows

New versions of PIP are released occasionally. These versions may improve the functionality or be obligatory for security purposes.

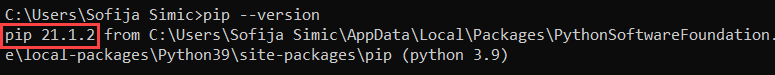

To check the current version of PIP, run:

pip --version

To upgrade PIP on Windows, enter the following in the command prompt:

python -m pip install --upgrade pipThis command uninstalls the old version of PIP and then installs the most current version of PIP.

Downgrade PIP Version

Downgrading may be necessary if a new version of PIP starts performing undesirably. To downgrade PIP to a prior version, specifying the version you want.

To downgrade PIP, use the syntax:

python -m pip install pip==version_numberFor example, to downgrade to version 18.1, you would run:

python -m pip install pip==18.1You should now see the version of PIP that you specified.

Conclusion

Congratulations, you have installed PIP for Python on Windows. Check out our other guides to learn how to install PIP on other operating systems:

- Install PIP on CentOS

- Install PIP on Ubuntu

- Install PIP on Debian

- Install PIP on Mac

Now that you have PIP up and running, you are ready to manage your Python packages.

NumPy is a library for the Python programming language, adding support for large, multi-dimensional arrays and matrices. Check out our guide and learn how to install NumPy using PIP.

Python 3.4+ and 2.7.9+

Good news! Python 3.4 (released March 2014) and Python 2.7.9 (released December 2014) ship with Pip. This is the best feature of any Python release. It makes the community’s wealth of libraries accessible to everyone. Newbies are no longer excluded from using community libraries by the prohibitive difficulty of setup. In shipping with a package manager, Python joins Ruby, Node.js, Haskell, Perl, Go—almost every other contemporary language with a majority open-source community. Thank you, Python.

If you do find that pip is not available, simply run ensurepip.

-

On Windows:

py -3 -m ensurepip -

Otherwise:

python3 -m ensurepip

Of course, that doesn’t mean Python packaging is problem solved. The experience remains frustrating. I discuss this in the Stack Overflow question Does Python have a package/module management system?.

Python 3 ≤ 3.3 and 2 ≤ 2.7.8

Flying in the face of its ‘batteries included’ motto, Python ships without a package manager. To make matters worse, Pip was—until recently—ironically difficult to install.

Official instructions

Per https://pip.pypa.io/en/stable/installing/#do-i-need-to-install-pip:

Download get-pip.py, being careful to save it as a .py file rather than .txt. Then, run it from the command prompt:

python get-pip.py

You possibly need an administrator command prompt to do this. Follow Start a Command Prompt as an Administrator (Microsoft TechNet).

This installs the pip package, which (in Windows) contains …Scriptspip.exe that path must be in PATH environment variable to use pip from the command line (see the second part of ‘Alternative Instructions’ for adding it to your PATH,

Alternative instructions

The official documentation tells users to install Pip and each of its dependencies from source. That’s tedious for the experienced and prohibitively difficult for newbies.

For our sake, Christoph Gohlke prepares Windows installers (.msi) for popular Python packages. He builds installers for all Python versions, both 32 and 64 bit. You need to:

- Install setuptools

- Install pip

For me, this installed Pip at C:Python27Scriptspip.exe. Find pip.exe on your computer, then add its folder (for example, C:Python27Scripts) to your path (Start / Edit environment variables). Now you should be able to run pip from the command line. Try installing a package:

pip install httpie

There you go (hopefully)! Solutions for common problems are given below:

Proxy problems

If you work in an office, you might be behind an HTTP proxy. If so, set the environment variables http_proxy and https_proxy. Most Python applications (and other free software) respect these. Example syntax:

http://proxy_url:port

http://username:password@proxy_url:port

If you’re really unlucky, your proxy might be a Microsoft NTLM proxy. Free software can’t cope. The only solution is to install a free software friendly proxy that forwards to the nasty proxy. http://cntlm.sourceforge.net/

Unable to find vcvarsall.bat

Python modules can be partly written in C or C++. Pip tries to compile from source. If you don’t have a C/C++ compiler installed and configured, you’ll see this cryptic error message.

Error: Unable to find vcvarsall.bat

You can fix that by installing a C++ compiler such as MinGW or Visual C++. Microsoft actually ships one specifically for use with Python. Or try Microsoft Visual C++ Compiler for Python 2.7.

Often though it’s easier to check Christoph’s site for your package.

Prerequisite: Python Language Introduction

Before we start with how to install pip for Python on Windows, let’s first go through the basic introduction to Python. Python is a widely-used general-purpose, high-level programming language. Python is a programming language that lets you work quickly and integrate systems more efficiently.

PIP is a package management system used to install and manage software packages/libraries written in Python. These files are stored in a large “online repository” termed as Python Package Index (PyPI). pip uses PyPI as the default source for packages and their dependencies. So whenever you type:

pip install package_name

pip will look for that package on PyPI and if found, it will download and install the package on your local system.

Check if Python is installed

Run the following command to test if python is installed or not. If not click here.

python --version

If it is installed, You will see something like this:

Python 3.10.0

Download and Install pip

The PIP can be downloaded and installed using the command line by going through the following steps:

Method 1: Using cURL in Python

Curl is a UNIX command that is used to send the PUT, GET, and POST requests to a URL. This tool is utilized for downloading files, testing REST APIs, etc.

Step 1: Open the cmd terminal

Step 2: In python, a curl is a tool for transferring data requests to and from a server. Use the following command to request:

curl https://bootstrap.pypa.io/get-pip.py -o get-pip.py

python get-pip.py

Method 2: Manually install PIP on Windows

Pip must be manually installed on Windows. You might need to use the correct version of the file from pypa.org if you’re using an earlier version of Python or pip. Get the file and save it to a folder on your PC.

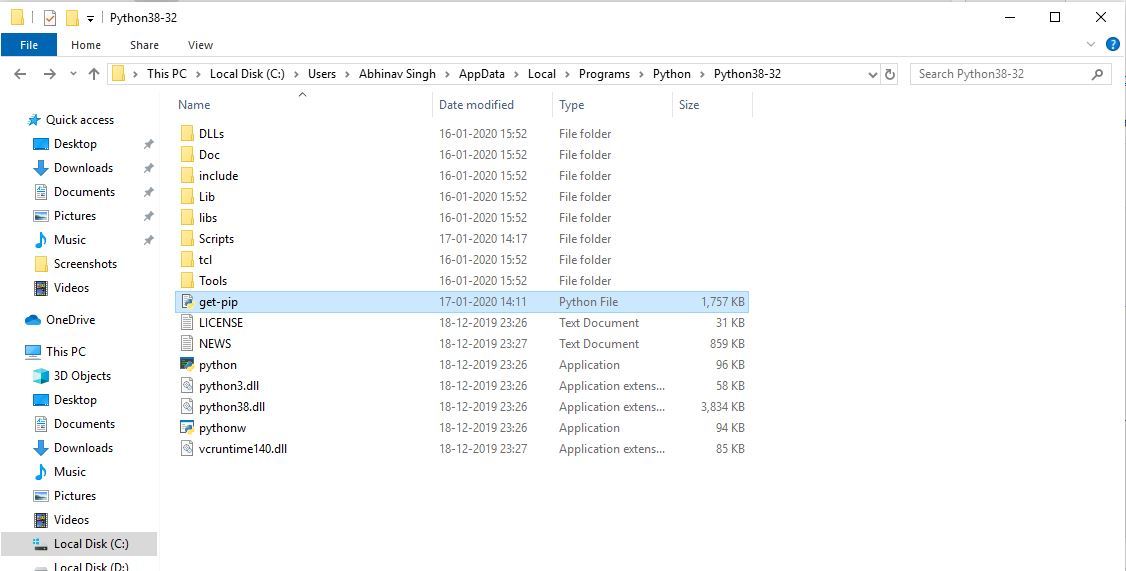

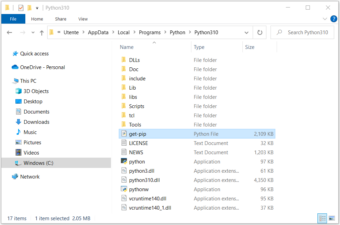

Step 1: Download the get-pip.py (https://bootstrap.pypa.io/get-pip.py) file and store it in the same directory as python is installed.

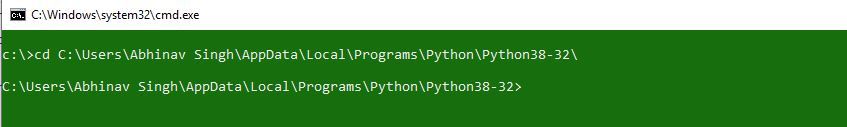

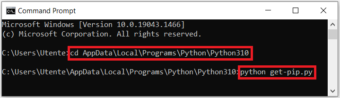

Step 2: Change the current path of the directory in the command line to the path of the directory where the above file exists.

Step 3: get-pip.py is a bootstrapping script that enables users to install pip in Python environments. Run the command given below:

python get-pip.py

Step 4: Now wait through the installation process. Voila! pip is now installed on your system.

Verification of the installation process

One can easily verify if the pip has been installed correctly by performing a version check on the same. Just go to the command line and execute the following command:

pip -V or pip --version

Adding PIP To Windows Environment Variables

If you are facing any path error then you can follow the following steps to add the pip to your PATH. You can follow the following steps to set the Path:

- Go to System and Security > System in the Control Panel once it has been opened.

- On the left side, click the Advanced system settings link.

- Then select Environment Variables.

- Double-click the PATH variable under System Variables.

- Click New, and add the directory where pip is installed, e.g. C:Python33Scripts, and select OK.

Upgrading Pip On Windows

pip can be upgraded using the following command.

python -m pip install -U pip

Downgrading Pip On Windows

It may happen sometimes that your pip current pip version is not supporting your current version of python or machine for that you can downgrade your pip version with the following command.

Note: You can mention the version you want to install

python -m pip install pip==17.0

User Guide

Running pip

pip is a command line program. When you install pip, a pip command is added

to your system, which can be run from the command prompt as follows:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: shell

python -m pip <pip arguments>

``python -m pip`` executes pip using the Python interpreter you

specified as python. So ``/usr/bin/python3.7 -m pip`` means

you are executing pip for your interpreter located at ``/usr/bin/python3.7``.

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: shell

py -m pip <pip arguments>

``py -m pip`` executes pip using the latest Python interpreter you

have installed. For more details, read the `Python Windows launcher`_ docs.

Installing Packages

pip supports installing from PyPI, version control, local projects, and

directly from distribution files.

The most common scenario is to install from PyPI using :ref:`Requirement

Specifiers`

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: shell

python -m pip install SomePackage # latest version

python -m pip install SomePackage==1.0.4 # specific version

python -m pip install 'SomePackage>=1.0.4' # minimum version

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: shell

py -m pip install SomePackage # latest version

py -m pip install SomePackage==1.0.4 # specific version

py -m pip install 'SomePackage>=1.0.4' # minimum version

For more information and examples, see the :ref:`pip install` reference.

Basic Authentication Credentials

This is now covered in :doc:`topics/authentication`.

netrc Support

This is now covered in :doc:`topics/authentication`.

Keyring Support

This is now covered in :doc:`topics/authentication`.

Using a Proxy Server

When installing packages from PyPI, pip requires internet access, which

in many corporate environments requires an outbound HTTP proxy server.

pip can be configured to connect through a proxy server in various ways:

- using the

--proxycommand-line option to specify a proxy in the form

scheme://[user:passwd@]proxy.server:port - using

proxyin a :ref:`config-file` - by setting the standard environment-variables

http_proxy,https_proxy

andno_proxy. - using the environment variable

PIP_USER_AGENT_USER_DATAto include

a JSON-encoded string in the user-agent variable used in pip’s requests.

Requirements Files

«Requirements files» are files containing a list of items to be

installed using :ref:`pip install` like so:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: shell

python -m pip install -r requirements.txt

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: shell

py -m pip install -r requirements.txt

Details on the format of the files are here: :ref:`requirements-file-format`.

Logically, a Requirements file is just a list of :ref:`pip install` arguments

placed in a file. Note that you should not rely on the items in the file being

installed by pip in any particular order.

In practice, there are 4 common uses of Requirements files:

-

Requirements files are used to hold the result from :ref:`pip freeze` for the

purpose of achieving :doc:`topics/repeatable-installs`. In

this case, your requirement file contains a pinned version of everything that

was installed whenpip freezewas run... tab:: Unix/macOS .. code-block:: shell python -m pip freeze > requirements.txt python -m pip install -r requirements.txt.. tab:: Windows .. code-block:: shell py -m pip freeze > requirements.txt py -m pip install -r requirements.txt -

Requirements files are used to force pip to properly resolve dependencies.

pip 20.2 and earlier doesn’t have true dependency resolution, but instead simply uses the first

specification it finds for a project. E.g. ifpkg1requires

pkg3>=1.0andpkg2requirespkg3>=1.0,<=2.0, and ifpkg1is

resolved first, pip will only usepkg3>=1.0, and could easily end up

installing a version ofpkg3that conflicts with the needs ofpkg2.

To solve this problem, you can placepkg3>=1.0,<=2.0(i.e. the correct

specification) into your requirements file directly along with the other top

level requirements. Like so:pkg1 pkg2 pkg3>=1.0,<=2.0

-

Requirements files are used to force pip to install an alternate version of a

sub-dependency. For example, supposeProjectAin your requirements file

requiresProjectB, but the latest version (v1.3) has a bug, you can force

pip to accept earlier versions like so:ProjectA ProjectB<1.3

-

Requirements files are used to override a dependency with a local patch that

lives in version control. For example, suppose a dependency

SomeDependencyfrom PyPI has a bug, and you can’t wait for an upstream

fix.

You could clone/copy the src, make the fix, and place it in VCS with the tag

sometag. You’d reference it in your requirements file with a line like

so:git+https://myvcs.com/some_dependency@sometag#egg=SomeDependency

If

SomeDependencywas previously a top-level requirement in your

requirements file, then replace that line with the new line. If

SomeDependencyis a sub-dependency, then add the new line.

It’s important to be clear that pip determines package dependencies using

install_requires metadata,

not by discovering requirements.txt files embedded in projects.

See also:

- :ref:`requirements-file-format`

- :ref:`pip freeze`

- «setup.py vs requirements.txt» (an article by Donald Stufft)

Constraints Files

Constraints files are requirements files that only control which version of a

requirement is installed, not whether it is installed or not. Their syntax and

contents is a subset of :ref:`Requirements Files`, with several kinds of syntax

not allowed: constraints must have a name, they cannot be editable, and they

cannot specify extras. In terms of semantics, there is one key difference:

Including a package in a constraints file does not trigger installation of the

package.

Use a constraints file like so:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: shell

python -m pip install -c constraints.txt

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: shell

py -m pip install -c constraints.txt

Constraints files are used for exactly the same reason as requirements files

when you don’t know exactly what things you want to install. For instance, say

that the «helloworld» package doesn’t work in your environment, so you have a

local patched version. Some things you install depend on «helloworld», and some

don’t.

One way to ensure that the patched version is used consistently is to

manually audit the dependencies of everything you install, and if «helloworld»

is present, write a requirements file to use when installing that thing.

Constraints files offer a better way: write a single constraints file for your

organisation and use that everywhere. If the thing being installed requires

«helloworld» to be installed, your fixed version specified in your constraints

file will be used.

Constraints file support was added in pip 7.1. In :ref:`Resolver

changes 2020` we did a fairly comprehensive overhaul, removing several

undocumented and unsupported quirks from the previous implementation,

and stripped constraints files down to being purely a way to specify

global (version) limits for packages.

Installing from Wheels

«Wheel» is a built, archive format that can greatly speed installation compared

to building and installing from source archives. For more information, see the

Wheel docs , PEP 427, and PEP 425.

pip prefers Wheels where they are available. To disable this, use the

:ref:`—no-binary <install_—no-binary>` flag for :ref:`pip install`.

If no satisfactory wheels are found, pip will default to finding source

archives.

To install directly from a wheel archive:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: shell

python -m pip install SomePackage-1.0-py2.py3-none-any.whl

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: shell

py -m pip install SomePackage-1.0-py2.py3-none-any.whl

To include optional dependencies provided in the provides_extras

metadata in the wheel, you must add quotes around the install target

name:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: shell

python -m pip install './somepackage-1.0-py2.py3-none-any.whl[my-extras]'

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: shell

py -m pip install './somepackage-1.0-py2.py3-none-any.whl[my-extras]'

Note

In the future, the path[extras] syntax may become deprecated. It is

recommended to use PEP 508 syntax wherever possible.

For the cases where wheels are not available, pip offers :ref:`pip wheel` as a

convenience, to build wheels for all your requirements and dependencies.

:ref:`pip wheel` requires the wheel package to be installed, which provides the

«bdist_wheel» setuptools extension that it uses.

To build wheels for your requirements and all their dependencies to a local

directory:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: shell

python -m pip install wheel

python -m pip wheel --wheel-dir=/local/wheels -r requirements.txt

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: shell

py -m pip install wheel

py -m pip wheel --wheel-dir=/local/wheels -r requirements.txt

And then to install those requirements just using your local directory of

wheels (and not from PyPI):

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: shell

python -m pip install --no-index --find-links=/local/wheels -r requirements.txt

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: shell

py -m pip install --no-index --find-links=/local/wheels -r requirements.txt

Uninstalling Packages

pip is able to uninstall most packages like so:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: shell

python -m pip uninstall SomePackage

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: shell

py -m pip uninstall SomePackage

pip also performs an automatic uninstall of an old version of a package

before upgrading to a newer version.

For more information and examples, see the :ref:`pip uninstall` reference.

Listing Packages

To list installed packages:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: console

$ python -m pip list

docutils (0.9.1)

Jinja2 (2.6)

Pygments (1.5)

Sphinx (1.1.2)

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: console

C:> py -m pip list

docutils (0.9.1)

Jinja2 (2.6)

Pygments (1.5)

Sphinx (1.1.2)

To list outdated packages, and show the latest version available:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: console

$ python -m pip list --outdated

docutils (Current: 0.9.1 Latest: 0.10)

Sphinx (Current: 1.1.2 Latest: 1.1.3)

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: console

C:> py -m pip list --outdated

docutils (Current: 0.9.1 Latest: 0.10)

Sphinx (Current: 1.1.2 Latest: 1.1.3)

To show details about an installed package:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: console

$ python -m pip show sphinx

---

Name: Sphinx

Version: 1.1.3

Location: /my/env/lib/pythonx.x/site-packages

Requires: Pygments, Jinja2, docutils

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: console

C:> py -m pip show sphinx

---

Name: Sphinx

Version: 1.1.3

Location: /my/env/lib/pythonx.x/site-packages

Requires: Pygments, Jinja2, docutils

For more information and examples, see the :ref:`pip list` and :ref:`pip show`

reference pages.

Searching for Packages

pip can search PyPI for packages using the pip search

command:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: shell

python -m pip search "query"

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: shell

py -m pip search "query"

The query will be used to search the names and summaries of all

packages.

For more information and examples, see the :ref:`pip search` reference.

Configuration

This is now covered in :doc:`topics/configuration`.

Config file

This is now covered in :doc:`topics/configuration`.

Environment Variables

This is now covered in :doc:`topics/configuration`.

Config Precedence

This is now covered in :doc:`topics/configuration`.

Command Completion

pip comes with support for command line completion in bash, zsh and fish.

To setup for bash:

python -m pip completion --bash >> ~/.profile

To setup for zsh:

python -m pip completion --zsh >> ~/.zprofile

To setup for fish:

python -m pip completion --fish > ~/.config/fish/completions/pip.fish

To setup for powershell:

python -m pip completion --powershell | Out-File -Encoding default -Append $PROFILE

Alternatively, you can use the result of the completion command directly

with the eval function of your shell, e.g. by adding the following to your

startup file:

eval "`pip completion --bash`"

Installing from local packages

In some cases, you may want to install from local packages only, with no traffic

to PyPI.

First, download the archives that fulfill your requirements:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: shell

python -m pip download --destination-directory DIR -r requirements.txt

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: shell

py -m pip download --destination-directory DIR -r requirements.txt

Note that pip download will look in your wheel cache first, before

trying to download from PyPI. If you’ve never installed your requirements

before, you won’t have a wheel cache for those items. In that case, if some of

your requirements don’t come as wheels from PyPI, and you want wheels, then run

this instead:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: shell

python -m pip wheel --wheel-dir DIR -r requirements.txt

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: shell

py -m pip wheel --wheel-dir DIR -r requirements.txt

Then, to install from local only, you’ll be using :ref:`—find-links

<install_—find-links>` and :ref:`—no-index <install_—no-index>` like so:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: shell

python -m pip install --no-index --find-links=DIR -r requirements.txt

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: shell

py -m pip install --no-index --find-links=DIR -r requirements.txt

«Only if needed» Recursive Upgrade

pip install --upgrade now has a --upgrade-strategy option which

controls how pip handles upgrading of dependencies. There are 2 upgrade

strategies supported:

eager: upgrades all dependencies regardless of whether they still satisfy

the new parent requirementsonly-if-needed: upgrades a dependency only if it does not satisfy the new

parent requirements

The default strategy is only-if-needed. This was changed in pip 10.0 due to

the breaking nature of eager when upgrading conflicting dependencies.

It is important to note that --upgrade affects direct requirements (e.g.

those specified on the command-line or via a requirements file) while

--upgrade-strategy affects indirect requirements (dependencies of direct

requirements).

As an example, say SomePackage has a dependency, SomeDependency, and

both of them are already installed but are not the latest available versions:

pip install SomePackage: will not upgrade the existingSomePackageor

SomeDependency.pip install --upgrade SomePackage: will upgradeSomePackage, but not

SomeDependency(unless a minimum requirement is not met).pip install --upgrade SomePackage --upgrade-strategy=eager: upgrades both

SomePackageandSomeDependency.

As an historic note, an earlier «fix» for getting the only-if-needed

behaviour was:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: shell

python -m pip install --upgrade --no-deps SomePackage

python -m pip install SomePackage

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: shell

py -m pip install --upgrade --no-deps SomePackage

py -m pip install SomePackage

A proposal for an upgrade-all command is being considered as a safer

alternative to the behaviour of eager upgrading.

User Installs

With Python 2.6 came the «user scheme» for installation,

which means that all Python distributions support an alternative install

location that is specific to a user. The default location for each OS is

explained in the python documentation for the site.USER_BASE variable.

This mode of installation can be turned on by specifying the :ref:`—user

<install_—user>` option to pip install.

Moreover, the «user scheme» can be customized by setting the

PYTHONUSERBASE environment variable, which updates the value of

site.USER_BASE.

To install «SomePackage» into an environment with site.USER_BASE customized to

‘/myappenv’, do the following:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: shell

export PYTHONUSERBASE=/myappenv

python -m pip install --user SomePackage

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: shell

set PYTHONUSERBASE=c:/myappenv

py -m pip install --user SomePackage

pip install --user follows four rules:

- When globally installed packages are on the python path, and they conflict

with the installation requirements, they are ignored, and not

uninstalled. - When globally installed packages are on the python path, and they satisfy

the installation requirements, pip does nothing, and reports that

requirement is satisfied (similar to how global packages can satisfy

requirements when installing packages in a--system-site-packages

virtualenv). - pip will not perform a

--userinstall in a--no-site-packages

virtualenv (i.e. the default kind of virtualenv), due to the user site not

being on the python path. The installation would be pointless. - In a

--system-site-packagesvirtualenv, pip will not install a package

that conflicts with a package in the virtualenv site-packages. The —user

installation would lack sys.path precedence and be pointless.

To make the rules clearer, here are some examples:

From within a --no-site-packages virtualenv (i.e. the default kind):

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: console

$ python -m pip install --user SomePackage

Can not perform a '--user' install. User site-packages are not visible in this virtualenv.

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: console

C:> py -m pip install --user SomePackage

Can not perform a '--user' install. User site-packages are not visible in this virtualenv.

From within a --system-site-packages virtualenv where SomePackage==0.3

is already installed in the virtualenv:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: console

$ python -m pip install --user SomePackage==0.4

Will not install to the user site because it will lack sys.path precedence

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: console

C:> py -m pip install --user SomePackage==0.4

Will not install to the user site because it will lack sys.path precedence

From within a real python, where SomePackage is not installed globally:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: console

$ python -m pip install --user SomePackage

[...]

Successfully installed SomePackage

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: console

C:> py -m pip install --user SomePackage

[...]

Successfully installed SomePackage

From within a real python, where SomePackage is installed globally, but

is not the latest version:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: console

$ python -m pip install --user SomePackage

[...]

Requirement already satisfied (use --upgrade to upgrade)

$ python -m pip install --user --upgrade SomePackage

[...]

Successfully installed SomePackage

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: console

C:> py -m pip install --user SomePackage

[...]

Requirement already satisfied (use --upgrade to upgrade)

C:> py -m pip install --user --upgrade SomePackage

[...]

Successfully installed SomePackage

From within a real python, where SomePackage is installed globally, and

is the latest version:

.. tab:: Unix/macOS

.. code-block:: console

$ python -m pip install --user SomePackage

[...]

Requirement already satisfied (use --upgrade to upgrade)

$ python -m pip install --user --upgrade SomePackage

[...]

Requirement already up-to-date: SomePackage

# force the install

$ python -m pip install --user --ignore-installed SomePackage

[...]

Successfully installed SomePackage

.. tab:: Windows

.. code-block:: console

C:> py -m pip install --user SomePackage

[...]

Requirement already satisfied (use --upgrade to upgrade)

C:> py -m pip install --user --upgrade SomePackage

[...]

Requirement already up-to-date: SomePackage

# force the install

C:> py -m pip install --user --ignore-installed SomePackage

[...]

Successfully installed SomePackage

Ensuring Repeatability

This is now covered in :doc:`../topics/repeatable-installs`.

Fixing conflicting dependencies

This is now covered in :doc:`../topics/dependency-resolution`.

Using pip from your program

As noted previously, pip is a command line program. While it is implemented in

Python, and so is available from your Python code via import pip, you must

not use pip’s internal APIs in this way. There are a number of reasons for this:

- The pip code assumes that it is in sole control of the global state of the

program.

pip manages things like the logging system configuration, or the values of

the standard IO streams, without considering the possibility that user code

might be affected. - pip’s code is not thread safe. If you were to run pip in a thread, there

is no guarantee that either your code or pip’s would work as you expect. - pip assumes that once it has finished its work, the process will terminate.

It doesn’t need to handle the possibility that other code will continue to

run after that point, so (for example) calling pip twice in the same process

is likely to have issues.

This does not mean that the pip developers are opposed in principle to the idea

that pip could be used as a library — it’s just that this isn’t how it was

written, and it would be a lot of work to redesign the internals for use as a

library, handling all of the above issues, and designing a usable, robust and

stable API that we could guarantee would remain available across multiple

releases of pip. And we simply don’t currently have the resources to even

consider such a task.

What this means in practice is that everything inside of pip is considered an

implementation detail. Even the fact that the import name is pip is subject

to change without notice. While we do try not to break things as much as

possible, all the internal APIs can change at any time, for any reason. It also

means that we generally won’t fix issues that are a result of using pip in an

unsupported way.

It should also be noted that installing packages into sys.path in a running

Python process is something that should only be done with care. The import

system caches certain data, and installing new packages while a program is

running may not always behave as expected. In practice, there is rarely an

issue, but it is something to be aware of.

Having said all of the above, it is worth covering the options available if you

decide that you do want to run pip from within your program. The most reliable

approach, and the one that is fully supported, is to run pip in a subprocess.

This is easily done using the standard subprocess module:

subprocess.check_call([sys.executable, '-m', 'pip', 'install', 'my_package'])

If you want to process the output further, use one of the other APIs in the module.

We are using freeze here which outputs installed packages in requirements format.:

reqs = subprocess.check_output([sys.executable, '-m', 'pip', 'freeze'])

If you don’t want to use pip’s command line functionality, but are rather

trying to implement code that works with Python packages, their metadata, or

PyPI, then you should consider other, supported, packages that offer this type

of ability. Some examples that you could consider include:

packaging— Utilities to work with standard package metadata (versions,

requirements, etc.)setuptools(specificallypkg_resources) — Functions for querying what

packages the user has installed on their system.distlib— Packaging and distribution utilities (including functions for

interacting with PyPI).

Changes to the pip dependency resolver in 20.3 (2020)

pip 20.3 has a new dependency resolver, on by default for Python 3

users. (pip 20.1 and 20.2 included pre-release versions of the new

dependency resolver, hidden behind optional user flags.) Read below

for a migration guide, how to invoke the legacy resolver, and the

deprecation timeline. We also made a two-minute video explanation

you can watch.

We will continue to improve the pip dependency resolver in response to

testers’ feedback. Please give us feedback through the resolver

testing survey.

Watch out for

The big change in this release is to the pip dependency resolver

within pip.

Computers need to know the right order to install pieces of software

(«to install x, you need to install y first»). So, when Python

programmers share software as packages, they have to precisely describe

those installation prerequisites, and pip needs to navigate tricky

situations where it’s getting conflicting instructions. This new

dependency resolver will make pip better at handling that tricky

logic, and make pip easier for you to use and troubleshoot.

The most significant changes to the resolver are:

- It will reduce inconsistency: it will no longer install a

combination of packages that is mutually inconsistent. In older

versions of pip, it is possible for pip to install a package which

does not satisfy the declared requirements of another installed

package. For example, in pip 20.0,pip install "six<1.12"does the wrong thing, “successfully” installing

"virtualenv==20.0.2"

six==1.11, even thoughvirtualenv==20.0.2requires

six>=1.12.0,<2(defined here).

The new resolver, instead, outright rejects installing anything if it

gets that input. - It will be stricter — if you ask pip to install two packages with

incompatible requirements, it will refuse (rather than installing a

broken combination, like it did in previous versions).

So, if you have been using workarounds to force pip to deal with

incompatible or inconsistent requirements combinations, now’s a good

time to fix the underlying problem in the packages, because pip will

be stricter from here on out.

This also means that, when you run a pip install command, pip only

considers the packages you are installing in that command, and may

break already-installed packages. It will not guarantee that your

environment will be consistent all the time. If you pip install x

and then pip install y, it’s possible that the version of y

you get will be different than it would be if you had run pip in a single command. We are considering changing this

install x y

behavior (per :issue:`7744`) and would like your thoughts on what

pip’s behavior should be; please answer our survey on upgrades that

create conflicts.

We are also changing our support for :ref:`Constraints Files`,

editable installs, and related functionality. We did a fairly

comprehensive overhaul and stripped constraints files down to being

purely a way to specify global (version) limits for packages, and so

some combinations that used to be allowed will now cause

errors. Specifically:

- Constraints don’t override the existing requirements; they simply

constrain what versions are visible as input to the resolver (see

:issue:`9020`) - Providing an editable requirement (

-e .) does not cause pip to

ignore version specifiers or constraints (see :issue:`8076`), and if

you have a conflict between a pinned requirement and a local

directory then pip will indicate that it cannot find a version

satisfying both (see :issue:`8307`) - Hash-checking mode requires that all requirements are specified as a

==match on a version and may not work well in combination with

constraints (see :issue:`9020` and :issue:`8792`) - If necessary to satisfy constraints, pip will happily reinstall

packages, upgrading or downgrading, without needing any additional

command-line options (see :issue:`8115` and :doc:`development/architecture/upgrade-options`) - Unnamed requirements are not allowed as constraints (see :issue:`6628` and :issue:`8210`)

- Links are not allowed as constraints (see :issue:`8253`)

- Constraints cannot have extras (see :issue:`6628`)

Per our :ref:`Python 2 Support` policy, pip 20.3 users who are using

Python 2 will use the legacy resolver by default. Python 2 users

should upgrade to Python 3 as soon as possible, since in pip 21.0 in

January 2021, pip dropped support for Python 2 altogether.

How to upgrade and migrate

-

Install pip 20.3 with

python -m pip install --upgrade pip. -

Validate your current environment by running

pip check. This

will report if you have any inconsistencies in your set of installed

packages. Having a clean installation will make it much less likely

that you will hit issues with the new resolver (and may

address hidden problems in your current environment!). If you run

pip checkand run into stuff you can’t figure out, please ask

for help in our issue tracker or chat. -

Test the new version of pip.

While we have tried to make sure that pip’s test suite covers as

many cases as we can, we are very aware that there are people using

pip with many different workflows and build processes, and we will

not be able to cover all of those without your help.- If you use pip to install your software, try out the new resolver

and let us know if it works for you withpip install. Try:- installing several packages simultaneously

- re-creating an environment using a

requirements.txtfile - using

pip install --force-reinstallto check whether

it does what you think it should - using constraints files

- the «Setups to test with special attention» and «Examples to try» below

- If you have a build pipeline that depends on pip installing your

dependencies for you, check that the new resolver does what you

need. - Run your project’s CI (test suite, build process, etc.) using the

new resolver, and let us know of any issues. - If you have encountered resolver issues with pip in the past,

check whether the new resolver fixes them, and read :ref:`Fixing

conflicting dependencies`. Also, let us know if the new resolver

has issues with any workarounds you put in to address the

current resolver’s limitations. We’ll need to ensure that people

can transition off such workarounds smoothly. - If you develop or support a tool that wraps pip or uses it to

deliver part of your functionality, please test your integration

with pip 20.3.

- If you use pip to install your software, try out the new resolver

-

Troubleshoot and try these workarounds if necessary.

- If pip is taking longer to install packages, read :doc:`Dependency

resolution backtracking <topics/dependency-resolution>` for ways to

reduce the time pip spends backtracking due to dependency conflicts. - If you don’t want pip to actually resolve dependencies, use the

--no-depsoption. This is useful when you have a set of package

versions that work together in reality, even though their metadata says

that they conflict. For guidance on a long-term fix, read

:ref:`Fixing conflicting dependencies`. - If you run into resolution errors and need a workaround while you’re

fixing their root causes, you can choose the old resolver behavior using

the flag--use-deprecated=legacy-resolver. This will work until we

release pip 21.0 (see

:ref:`Deprecation timeline for 2020 resolver changes`).

- If pip is taking longer to install packages, read :doc:`Dependency

-

Please report bugs through the resolver testing survey.

Setups to test with special attention

- Requirements files with 100+ packages

- Installation workflows that involve multiple requirements files

- Requirements files that include hashes (:ref:`hash-checking mode`)

or pinned dependencies (perhaps as output frompip-compilewithin

pip-tools) - Using :ref:`Constraints Files`

- Continuous integration/continuous deployment setups

- Installing from any kind of version control systems (i.e., Git, Subversion, Mercurial, or CVS), per :doc:`topics/vcs-support`

- Installing from source code held in local directories

Examples to try

Install:

- tensorflow

hackingpycodestylepandastablibelasticsearchandrequeststogethersixandcherrypytogetherpip install flake8-import-order==0.17.1 flake8==3.5.0 --use-feature=2020-resolverpip install tornado==5.0 sprockets.http==1.5.0 --use-feature=2020-resolver

Try:

pip installpip uninstallpip checkpip cache

Tell us about

Specific things we’d love to get feedback on:

- Cases where the new resolver produces the wrong result,

obviously. We hope there won’t be too many of these, but we’d like

to trap such bugs before we remove the legacy resolver. - Cases where the resolver produced an error when you believe it

should have been able to work out what to do. - Cases where the resolver gives an error because there’s a problem

with your requirements, but you need better information to work out

what’s wrong. - If you have workarounds to address issues with the current resolver,

does the new resolver let you remove those workarounds? Tell us!

Please let us know through the resolver testing survey.

Deprecation timeline

We plan for the resolver changeover to proceed as follows, using

:ref:`Feature Flags` and following our :ref:`Release Cadence`:

- pip 20.1: an alpha version of the new resolver was available,

opt-in, using the optional flag

--unstable-feature=resolver. pip defaulted to legacy

behavior. - pip 20.2: a beta of the new resolver was available, opt-in, using

the flag--use-feature=2020-resolver. pip defaulted to legacy

behavior. Users of pip 20.2 who want pip to default to using the

new resolver can runpip config set global.use-feature(for more on that and the alternate

2020-resolver

PIP_USE_FEATUREenvironment variable option, see issue

8661). - pip 20.3: pip defaults to the new resolver in Python 3 environments,

but a user can opt-out and choose the old resolver behavior,

using the flag--use-deprecated=legacy-resolver. In Python 2

environments, pip defaults to the old resolver, and the new one is

available using the flag--use-feature=2020-resolver. - pip 21.0: pip uses new resolver by default, and the old resolver is

no longer supported. It will be removed after a currently undecided

amount of time, as the removal is dependent on pip’s volunteer

maintainers’ availability. Python 2 support is removed per our

:ref:`Python 2 Support` policy.

Since this work will not change user-visible behavior described in the

pip documentation, this change is not covered by the :ref:`Deprecation

Policy`.

Context and followup

As discussed in our announcement on the PSF blog, the pip team are

in the process of developing a new «dependency resolver» (the part of

pip that works out what to install based on your requirements).

We’re tracking our rollout in :issue:`6536` and you can watch for

announcements on the low-traffic packaging announcements list and

the official Python blog.

Using system trust stores for verifying HTTPS

This is now covered in :doc:`topics/https-certificates`.

June 9, 2022

In this tutorial, we will identify PIP for Python, when we use it, how to install it, how to check its version, how to configure it on Windows, and how to upgrade (or downgrade) it.

What Is PIP for Python?

PIP stands for «PIP Installs Packages», which is a recursive acronym (the one that refers to itself) coined by its creator. In more practical terms, PIP is a widely used package-management system designed to install libraries that aren’t included in the standard distribution of the Python programming language on our local machine — and then manage them from the command line.

By default, PIP fetches such libraries from Python Package Index (PyPI), which is a central online repository containing a vast collection of third-party packages for various applications. If necessary, PIP can also connect to another local or online repository as long as it complies to PEP 503.

How to Install PIP on Windows

Before proceeding to PIP installation on Windows, we need to make sure that Python is already installed and PIP is not installed.

Check If Python Is Available

To verify that Python is available on our local machine, we need to open the command line (in Windows search, type cmd and press Enter to open Command Prompt or right-click on the Start button and select Windows PowerShell), type python, and press Enter.

If Python is properly installed, we will see a notification like the one below:

Python 3.10.2 (tags/v3.10.2:a58ebcc, Jan 17 2022, 14:12:15) [MSC v.1929 64 bit (AMD64)] on win32 Type "help," "copyright," "credits," or "license" for more information.

In the opposite case, we will see the following notification:

'python' is not recognized as an internal or external command, operable program or batch file.

This means that Python is either not installed on our local machine or is installed incorrectly and needs setting system variables. If you need further guidance on how to properly install Python on Windows, you can use this article in the Dataquest blog: Tutorial: Installing Python on Windows.

Check If PIP Is Already Installed

Now that we verified that Python is installed on Windows (or, if it was not, have installed it), let’s check if PIP is already installed on our system.

The latest releases Python 3.4+ and Python 2.7.9+, as well as the virtual environments virtualenv and pyvenv, automatically ship with PIP (we can check our Python version by running python --version or python -V in the command line). However, the older versions of Python don’t have this advantage by default. If we use an older Python release and cannot upgrade it for some reason (e.g., when we have to work with the projects made in old versions of Python incompatible with the newer versions), we may need to manually download and install PIP on Windows.

To check if PIP is already installed on Windows, we should open the command line again, type pip, and press Enter.

If PIP is installed, we will receive a long notification explaining the program usage, all the available commands and options. Otherwise, if PIP is not installed, the output will be:

'pip' is not recognized as an internal or external command, operable program or batch file.

This is exactly the case when we have to manually install PIP on Windows.

Download PIP

Before installing PIP, we have to download the get-pip.py file. We can do this two ways:

- Go to https://bootstrap.pypa.io/get-pip.py and save this file as

get-pip.pyin the same folder where Python is located.

By default, the Python installation is stored in the folderAppData. The entire path could look like the following:

C:UsersUserAppDataLocalProgramsPythonPython310

The folder User can be called differently on a particular machine, and also the final folder in the above path depends on the version of Python. In our case – Python 3.10:

- Open the command line and navigate to the folder where Python is stored using the

cdcommand (see the previous point if you are not sure about Python’s location).

Now, run the following curl command:

curl https://bootstrap.pypa.io/get-pip.py -o get-pip.py

Install PIP on Windows

Now that we downloaded the get-pip.py file, we need to complete the followings steps.

- Open the command line

- Navigate to the folder where Python and the

get-pip.pyfile are stored using thecdcommand - Launch the installer by running the following command:

python get-pip.py

After a quick installation process, a message appears with all the details of the installation, and the final line appears as follows:

Successfully installed pip-22.0.1 wheel-0.37.1

PIP is now successfully installed on Windows.

Verify the PIP Installation Process and Check the PIP Version

To double-check if PIP has been installed properly and check its version, we need to run one of these commands in the command line:

pip --version

or

pip -V

If PIP is installed correctly, we will see a message indicating the version of PIP and its location on the local system, like the following:

pip 22.0.2 from C:UsersUtenteAppDataLocalProgramsPythonPython310libsite-packagespip (python 3.10).

If instead, an error is thrown, it is necessary to repeat the installation process.

Add PIP to Windows Environment Variables

To be able to run PIP without issues from any folder in the command line (rather than navigating every time to the folder where the PIP installer is stored, as we did earlier), we have to add the path to the folder with the get-pip.py file to Windows environment variables. This is especially important in that rare case when, we have installed several versions of Python, including old ones. In this situation, to avoid installing PIP separately for each old version of Python, we should install it only for one of them and then perform the following steps:

- Open

Control Panel(typing it in Windows search), selectSystem and Security, then selectSystem. - Go to the end of the opened window and select

Advanced system settings:

- Click

Environment Variables:

- In the

System variablessection, find and double-click the variablePath:

- Click

Newand add the path to the folder where the PIP installer is stored:

- Click

OKto confirm modifications.

Upgrade PIP on Windows

Sometimes, we may need to update PIP on Windows to the latest version to keep it up-to-date and working flawlessly. For this purpose, we can run the following command in the command line:

python -m pip install --upgrade pip

As a result, the old version of PIP will be uninstalled and the most recent release will be installed.

Downgrade PIP on Windows

We can also want to downgrade PIP to a specific older version. This operation may be necessary in certain cases, for example, if a new version works with some compatibility issues. To downgrade PIP on Windows, we need to open the command line and run a command with the following syntax:

python -m pip install pip==<version>

Let’s say, we want to downgrade it to v20.3. Then the exact command will be:

python -m pip install pip==20.3

After downgrading PIP, we can verify that we now have the necessary version of it by running python -V.

Conclusion

In this tutorial we covered various topics regarding the installation of PIP on Windows:

- How PIP works

- How to check if Python and PIP are already installed

- When it may be necessary to manually install PIP on Windows

- How to download and install PIP on Windows

- How to verify if PIP has been successfully installed and check its version

- How to configure PIP on Windows and when it may be necessary

- When and how to upgrade or downgrade PIP on Windows

Now that we have PIP properly installed on Windows, we can begin using it to manage Python libraries. Let’s start with running pip help in the command line and exploring the available commands and options for this program.

Contents

- User Guide

- Installing Packages

- Requirements Files

- Constraints Files

- Installing from Wheels

- Uninstalling Packages

- Listing Packages

- Searching for Packages

- Configuration

- Config file

- Environment Variables

- Config Precedence

- Command Completion

- Installing from local packages

- «Only if needed» Recursive Upgrade

- User Installs

- Ensuring Repeatability

- Pinned Version Numbers

- Hash-checking Mode

- Installation Bundles

Installing Packages¶

pip supports installing from PyPI, version control, local projects, and

directly from distribution files.

The most common scenario is to install from PyPI using Requirement Specifiers

$ pip install SomePackage # latest version $ pip install SomePackage==1.0.4 # specific version $ pip install 'SomePackage>=1.0.4' # minimum version

For more information and examples, see the pip install reference.

Requirements Files¶

«Requirements files» are files containing a list of items to be

installed using pip install like so:

pip install -r requirements.txt

Details on the format of the files are here: Requirements File Format.

Logically, a Requirements file is just a list of pip install arguments

placed in a file. Note that you should not rely on the items in the file being

installed by pip in any particular order.

In practice, there are 4 common uses of Requirements files:

-

Requirements files are used to hold the result from pip freeze for the

purpose of achieving repeatable installations. In

this case, your requirement file contains a pinned version of everything that

was installed when pip freeze was run.pip freeze > requirements.txt pip install -r requirements.txt

-

Requirements files are used to force pip to properly resolve dependencies.

As it is now, pip doesn’t have true dependency resolution, but instead simply uses the first

specification it finds for a project. E.g if pkg1 requires pkg3>=1.0 and

pkg2 requires pkg3>=1.0,<=2.0, and if pkg1 is resolved first, pip will

only use pkg3>=1.0, and could easily end up installing a version of pkg3

that conflicts with the needs of pkg2. To solve this problem, you can

place pkg3>=1.0,<=2.0 (i.e. the correct specification) into your

requirements file directly along with the other top level requirements. Like

so:pkg1 pkg2 pkg3>=1.0,<=2.0

-

Requirements files are used to force pip to install an alternate version of a

sub-dependency. For example, suppose ProjectA in your requirements file

requires ProjectB, but the latest version (v1.3) has a bug, you can force

pip to accept earlier versions like so: -

Requirements files are used to override a dependency with a local patch that

lives in version control. For example, suppose a dependency,

SomeDependency from PyPI has a bug, and you can’t wait for an upstream fix.

You could clone/copy the src, make the fix, and place it in VCS with the tag

sometag. You’d reference it in your requirements file with a line like so:git+https://myvcs.com/some_dependency@sometag#egg=SomeDependency

If SomeDependency was previously a top-level requirement in your

requirements file, then replace that line with the new line. If

SomeDependency is a sub-dependency, then add the new line.

It’s important to be clear that pip determines package dependencies using

install_requires metadata,

not by discovering requirements.txt files embedded in projects.

See also:

- Requirements File Format

- pip freeze

- «setup.py vs requirements.txt» (an article by Donald Stufft)

Constraints Files¶

Constraints files are requirements files that only control which version of a

requirement is installed, not whether it is installed or not. Their syntax and

contents is nearly identical to Requirements Files. There is one key

difference: Including a package in a constraints file does not trigger

installation of the package.

Use a constraints file like so:

pip install -c constraints.txt

Constraints files are used for exactly the same reason as requirements files

when you don’t know exactly what things you want to install. For instance, say

that the «helloworld» package doesn’t work in your environment, so you have a

local patched version. Some things you install depend on «helloworld», and some

don’t.

One way to ensure that the patched version is used consistently is to

manually audit the dependencies of everything you install, and if «helloworld»

is present, write a requirements file to use when installing that thing.

Constraints files offer a better way: write a single constraints file for your

organisation and use that everywhere. If the thing being installed requires

«helloworld» to be installed, your fixed version specified in your constraints

file will be used.

Constraints file support was added in pip 7.1.

Installing from Wheels¶

«Wheel» is a built, archive format that can greatly speed installation compared

to building and installing from source archives. For more information, see the

Wheel docs ,

PEP427, and

PEP425

Pip prefers Wheels where they are available. To disable this, use the

—no-binary flag for pip install.

If no satisfactory wheels are found, pip will default to finding source archives.

To install directly from a wheel archive:

pip install SomePackage-1.0-py2.py3-none-any.whl

For the cases where wheels are not available, pip offers pip wheel as a

convenience, to build wheels for all your requirements and dependencies.

pip wheel requires the wheel package to be installed, which provides the

«bdist_wheel» setuptools extension that it uses.

To build wheels for your requirements and all their dependencies to a local directory:

pip install wheel pip wheel --wheel-dir=/local/wheels -r requirements.txt

And then to install those requirements just using your local directory of wheels (and not from PyPI):

pip install --no-index --find-links=/local/wheels -r requirements.txt

Uninstalling Packages¶

pip is able to uninstall most packages like so:

$ pip uninstall SomePackage

pip also performs an automatic uninstall of an old version of a package

before upgrading to a newer version.

For more information and examples, see the pip uninstall reference.

Listing Packages¶

To list installed packages:

$ pip list docutils (0.9.1) Jinja2 (2.6) Pygments (1.5) Sphinx (1.1.2)

To list outdated packages, and show the latest version available:

$ pip list --outdated docutils (Current: 0.9.1 Latest: 0.10) Sphinx (Current: 1.1.2 Latest: 1.1.3)

To show details about an installed package:

$ pip show sphinx --- Name: Sphinx Version: 1.1.3 Location: /my/env/lib/pythonx.x/site-packages Requires: Pygments, Jinja2, docutils

For more information and examples, see the pip list and pip show

reference pages.

Searching for Packages¶

pip can search PyPI for packages using the pip search

command:

The query will be used to search the names and summaries of all

packages.

For more information and examples, see the pip search reference.

Configuration¶

Config file¶

pip allows you to set all command line option defaults in a standard ini

style config file.

The names and locations of the configuration files vary slightly across

platforms. You may have per-user, per-virtualenv or site-wide (shared amongst

all users) configuration:

Per-user:

- On Unix the default configuration file is:

$HOME/.config/pip/pip.conf

which respects theXDG_CONFIG_HOMEenvironment variable. - On macOS the configuration file is

$HOME/Library/Application Support/pip/pip.conf. - On Windows the configuration file is

%APPDATA%pippip.ini.

There are also a legacy per-user configuration file which is also respected,

these are located at:

- On Unix and macOS the configuration file is:

$HOME/.pip/pip.conf - On Windows the configuration file is:

%HOME%pippip.ini

You can set a custom path location for this config file using the environment

variable PIP_CONFIG_FILE.

Inside a virtualenv:

- On Unix and macOS the file is

$VIRTUAL_ENV/pip.conf - On Windows the file is:

%VIRTUAL_ENV%pip.ini

Site-wide:

- On Unix the file may be located in

/etc/pip.conf. Alternatively

it may be in a «pip» subdirectory of any of the paths set in the

environment variableXDG_CONFIG_DIRS(if it exists), for example

/etc/xdg/pip/pip.conf. - On macOS the file is:

/Library/Application Support/pip/pip.conf - On Windows XP the file is:

C:Documents and SettingsAll UsersApplication Datapippip.ini - On Windows 7 and later the file is hidden, but writeable at

C:ProgramDatapippip.ini - Site-wide configuration is not supported on Windows Vista

If multiple configuration files are found by pip then they are combined in

the following order:

- Firstly the site-wide file is read, then

- The per-user file is read, and finally

- The virtualenv-specific file is read.

Each file read overrides any values read from previous files, so if the

global timeout is specified in both the site-wide file and the per-user file

then the latter value is the one that will be used.

The names of the settings are derived from the long command line option, e.g.

if you want to use a different package index (--index-url) and set the

HTTP timeout (--default-timeout) to 60 seconds your config file would

look like this:

[global] timeout = 60 index-url = http://download.zope.org/ppix

Each subcommand can be configured optionally in its own section so that every

global setting with the same name will be overridden; e.g. decreasing the

timeout to 10 seconds when running the freeze

(Freezing Requirements) command and using

60 seconds for all other commands is possible with:

[global] timeout = 60 [freeze] timeout = 10

Boolean options like --ignore-installed or --no-dependencies can be

set like this:

[install] ignore-installed = true no-dependencies = yes

To enable the boolean options --no-compile and --no-cache-dir, falsy

values have to be used:

[global] no-cache-dir = false [install] no-compile = no

Appending options like --find-links can be written on multiple lines:

[global] find-links = http://download.example.com [install] find-links = http://mirror1.example.com http://mirror2.example.com

Environment Variables¶

pip’s command line options can be set with environment variables using the

format PIP_<UPPER_LONG_NAME> . Dashes (-) have to be replaced with

underscores (_).

For example, to set the default timeout:

export PIP_DEFAULT_TIMEOUT=60

This is the same as passing the option to pip directly:

pip --default-timeout=60 [...]

To set options that can be set multiple times on the command line, just add

spaces in between values. For example:

export PIP_FIND_LINKS="http://mirror1.example.com http://mirror2.example.com"

is the same as calling:

pip install --find-links=http://mirror1.example.com --find-links=http://mirror2.example.com

Config Precedence¶

Command line options have precedence over environment variables, which have precedence over the config file.

Within the config file, command specific sections have precedence over the global section.

Examples:

--host=foooverridesPIP_HOST=fooPIP_HOST=foooverrides a config file with[global] host = foo- A command specific section in the config file

[<command>] host = bar

overrides the option with same name in the[global]config file section

Command Completion¶

pip comes with support for command line completion in bash, zsh and fish.

To setup for bash:

$ pip completion --bash >> ~/.profile

To setup for zsh:

$ pip completion --zsh >> ~/.zprofile

To setup for fish:

$ pip completion --fish > ~/.config/fish/completions/pip.fish

Alternatively, you can use the result of the completion command

directly with the eval function of your shell, e.g. by adding the following to your startup file:

eval "`pip completion --bash`"

Installing from local packages¶

In some cases, you may want to install from local packages only, with no traffic

to PyPI.

First, download the archives that fulfill your requirements:

$ pip install --download DIR -r requirements.txt

Note that pip install --download will look in your wheel cache first, before

trying to download from PyPI. If you’ve never installed your requirements

before, you won’t have a wheel cache for those items. In that case, if some of

your requirements don’t come as wheels from PyPI, and you want wheels, then run

this instead:

$ pip wheel --wheel-dir DIR -r requirements.txt

Then, to install from local only, you’ll be using —find-links and —no-index like so:

$ pip install --no-index --find-links=DIR -r requirements.txt

«Only if needed» Recursive Upgrade¶

pip install --upgrade is currently written to perform an eager recursive

upgrade, i.e. it upgrades all dependencies regardless of whether they still

satisfy the new parent requirements.

E.g. supposing:

- SomePackage-1.0 requires AnotherPackage>=1.0

- SomePackage-2.0 requires AnotherPackage>=1.0 and OneMorePackage==1.0

- SomePackage-1.0 and AnotherPackage-1.0 are currently installed

- SomePackage-2.0 and AnotherPackage-2.0 are the latest versions available on PyPI.

Running pip install --upgrade SomePackage would upgrade SomePackage and

AnotherPackage despite AnotherPackage already being satisfied.

pip doesn’t currently have an option to do an «only if needed» recursive

upgrade, but you can achieve it using these 2 steps:

pip install --upgrade --no-deps SomePackage pip install SomePackage

The first line will upgrade SomePackage, but not dependencies like

AnotherPackage. The 2nd line will fill in new dependencies like

OneMorePackage.

See #59 for a plan of making «only if needed» recursive the default

behavior for a new pip upgrade command.

User Installs¶

With Python 2.6 came the «user scheme» for installation,

which means that all Python distributions support an alternative install

location that is specific to a user. The default location for each OS is

explained in the python documentation for the site.USER_BASE variable. This mode

of installation can be turned on by specifying the —user option to pip install.

Moreover, the «user scheme» can be customized by setting the

PYTHONUSERBASE environment variable, which updates the value of site.USER_BASE.

To install «SomePackage» into an environment with site.USER_BASE customized to ‘/myappenv’, do the following:

export PYTHONUSERBASE=/myappenv pip install --user SomePackage

pip install --user follows four rules:

- When globally installed packages are on the python path, and they conflict

with the installation requirements, they are ignored, and not

uninstalled. - When globally installed packages are on the python path, and they satisfy

the installation requirements, pip does nothing, and reports that

requirement is satisfied (similar to how global packages can satisfy

requirements when installing packages in a--system-site-packages

virtualenv). - pip will not perform a

--userinstall in a--no-site-packages

virtualenv (i.e. the default kind of virtualenv), due to the user site not

being on the python path. The installation would be pointless. - In a

--system-site-packagesvirtualenv, pip will not install a package

that conflicts with a package in the virtualenv site-packages. The —user

installation would lack sys.path precedence and be pointless.

To make the rules clearer, here are some examples:

From within a --no-site-packages virtualenv (i.e. the default kind):

$ pip install --user SomePackage Can not perform a '--user' install. User site-packages are not visible in this virtualenv.

From within a --system-site-packages virtualenv where SomePackage==0.3 is already installed in the virtualenv:

$ pip install --user SomePackage==0.4 Will not install to the user site because it will lack sys.path precedence

From within a real python, where SomePackage is not installed globally:

$ pip install --user SomePackage [...] Successfully installed SomePackage

From within a real python, where SomePackage is installed globally, but is not the latest version:

$ pip install --user SomePackage [...] Requirement already satisfied (use --upgrade to upgrade) $ pip install --user --upgrade SomePackage [...] Successfully installed SomePackage

From within a real python, where SomePackage is installed globally, and is the latest version:

$ pip install --user SomePackage [...] Requirement already satisfied (use --upgrade to upgrade) $ pip install --user --upgrade SomePackage [...] Requirement already up-to-date: SomePackage # force the install $ pip install --user --ignore-installed SomePackage [...] Successfully installed SomePackage

Ensuring Repeatability¶

pip can achieve various levels of repeatability:

Pinned Version Numbers¶

Pinning the versions of your dependencies in the requirements file

protects you from bugs or incompatibilities in newly released versions:

SomePackage == 1.2.3 DependencyOfSomePackage == 4.5.6

Using pip freeze to generate the requirements file will ensure that not

only the top-level dependencies are included but their sub-dependencies as

well, and so on. Perform the installation using —no-deps for an extra dose of insurance against installing

anything not explicitly listed.

This strategy is easy to implement and works across OSes and architectures.

However, it trusts PyPI and the certificate authority chain. It

also relies on indices and find-links locations not allowing

packages to change without a version increase. (PyPI does protect

against this.)

Hash-checking Mode¶

Beyond pinning version numbers, you can add hashes against which to verify

downloaded packages:

FooProject == 1.2 --hash=sha256:2cf24dba5fb0a30e26e83b2ac5b9e29e1b161e5c1fa7425e73043362938b9824

This protects against a compromise of PyPI or the HTTPS

certificate chain. It also guards against a package changing

without its version number changing (on indexes that allow this).

This approach is a good fit for automated server deployments.

Hash-checking mode is a labor-saving alternative to running a private index

server containing approved packages: it removes the need to upload packages,

maintain ACLs, and keep an audit trail (which a VCS gives you on the

requirements file for free). It can also substitute for a vendor library,

providing easier upgrades and less VCS noise. It does not, of course,

provide the availability benefits of a private index or a vendor library.

For more, see pip install’s discussion of hash-checking mode.

Installation Bundles¶

Using pip wheel, you can bundle up all of a project’s dependencies, with

any compilation done, into a single archive. This allows installation when

index servers are unavailable and avoids time-consuming recompilation. Create

an archive like this:

$ tempdir=$(mktemp -d /tmp/wheelhouse-XXXXX) $ pip wheel -r requirements.txt --wheel-dir=$tempdir $ cwd=`pwd` $ (cd "$tempdir"; tar -cjvf "$cwd/bundled.tar.bz2" *)

You can then install from the archive like this:

$ tempdir=$(mktemp -d /tmp/wheelhouse-XXXXX) $ (cd $tempdir; tar -xvf /path/to/bundled.tar.bz2) $ pip install --force-reinstall --ignore-installed --upgrade --no-index --no-deps $tempdir/*

Note that compiled packages are typically OS- and architecture-specific, so

these archives are not necessarily portable across machines.

Hash-checking mode can be used along with this method to ensure that future

archives are built with identical packages.

Warning

Finally, beware of the setup_requires keyword arg in setup.py.

The (rare) packages that use it will cause those dependencies to be

downloaded by setuptools directly, skipping pip’s protections. If you need

to use such a package, see Controlling

setup_requires.

Download Article

Download Article