Chapter 1. Introduction to C++

C++ is a large object-oriented language that supports many modern features. As the name implies, it is a further development of the language C. In this chapter, you will learn the basics of the language. The next chapter deals with the object-oriented parts of C++. This chapter covers:

-

An introduction to the languge, how the compiler and linker works, the overal structure of a program, and comments.

-

C++ is a typed language, which means that every value stored in the computer memory is well defined. The type can be an integer, a real value, a logical value, or a character.

-

An array is a sequence of values of the same type. Pointers and references hold the address of a value.

-

In C++ there are possibilities to calculate values by using the four fundamental rules of arithmetic. We can also compare values as well as perform logical and bitwise operations.

-

The flow of a program can be directed with statements. We can choose between two or more choices, repeat until a certain condition is fulfilled, and we can also jump to another location in the code.

-

A function is a part of the code designed to perform a specific task. It is called by the main program or by another function. It may take input, which is called parameters, and may also return a value.

-

The preprocessor is a tool that performs textual substitution by the means with macros. It is also possible to include text from other files and to include or exclude code.

The Compiler and the Linker

The text of a program is called its source code. The compiler is the program that translates the source code into target code, and the linker puts several compiled files into an executable file.

Let us say we have a C++ program in the source code file Prog.cpp and a routine used by the program in Routine.cpp. Furthermore, the program calls a function in the standard library. In this case, the compiler translates the source code into object code and the linker joins the code into the executable file Prog.exe.

If the compiler reports an error, we refer to it as compile-time error. In the same way, if an error occurs during the execution of the program, we call it a run-time error.

The First Program

The execution of a program always starts with the function main. Below is a program that prints the text Hello, World! on the screen.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void main()

{

cout << "Hello, World!" << endl;

}

Comments

In C++, it is possible to insert comments to describe and clarify the meaning of the program. The comments are ignored by the compiler (every comment is replaced by a single space character). There are two types of comments: line comments and block comments. Line comments start with two slashes and end at the end of the line.

cout << "Hello, World!" << endl; // Prints "Hello, World!".

Block comments begin with a slash and an asterisk and end with an asterisk and a slash. A block comment may range over several lines.

/* This is an example of a C++ program.

It prints the text "Hello, World!"

on the screen. */

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void main()

{

cout << "Hello, World!" << endl; // Prints "Hello, World!".

}

Block comments cannot be nested. The following example will result in a compile-time error.

/* A block comment cannot be /* nested */ inside another one. */

A piece of advice is that you use the line comments for regular comments, and save the block comments for situations when you need to comment a whole block of code for debugging purposes.

Types and Variables

There are several types in C++. They can be divided into two groups: simple and compounded. The simple types can be further classified into integral, floating, and logical types. The compunded types are arrays, pointers, and references. They are all (directly or indirectly) constituted by simple types. We can also define a type with our own values, called the enumeration type.

Simple Types

There are five simple types intended for storing integers: char, wchar_t, short int, int, and long int. They are called the integral types. The types short int and long int may be abbreviated to short and long, respectively. As the names imply, they are designed for storing characters, small integers, normal integers, and large integers, respectively. The exact limits of the values possible to store varies between different compilers.

Furthermore, the integral types may be signed or unsigned. An unsigned type must not have negative values. If the word signed or unsigned is left out, a short int, int, and long int will be signed. Whether a char will be signed or unsigned is not defined in the standard, but rather depends on the compiler and the underlying operational systems. We say that it is implementation-dependent.

However, a character of the type char is always one byte long, which means that it always holds a single character, regardless of whether it is unsigned or not. The type wchar_t is designed to hold a character of a more complex sort; therefore, it usually has a length of at least two bytes.

The char type is often based on the American Standard Code for Information Exchange (ASCII) table. Each character has a specific number ranging from 0 to 127 in the table. For instance, ‘a’ has the number 97. With the help of the ASCII table, we can convert between integers and characters. See the last section of this chapter for the complete ASCII table.

int i = (int) 'a'; // 97 char c = (char) 97; // 'a'

The next category of simple types is the floating types. They are used to store real values; that is, numbers with decimal fractions. The types are float, double, and long double, where float stores the smallest value and long double the largest one. The value size that each type can store depends on the compiler. A floating type cannot be unsigned.

The final simple type is bool. It is used to store logical values: true or false.

Variables

A variable can be viewed as a box in memory. In almost every case, we do not need to know the exact memory address the variable is stored on. A variable always has a name, a type, and a value. We define a variable by simply writing its type and name. If we want to, we can initialize the variable; that is, assign it a value. If we do not, the variable’s value will be undefined (it is given the value that happens to be on its memory location).

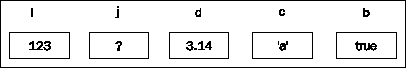

int i = 123, j; double d = 3.14; char c = 'a'; bool b = true;

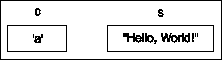

As a char is a small integer type, it is intended to store exactly one character. A string stores a (possibly empty) sequence of characters. There is no built-in type for describing a string; however, there is a library class string with some basic operations. Note that characters are enclosed by single quotations while strings are enclosed by double quotations. In order to use strings, we have to include the header file string and use the namespace std. Header files, classes, and namespaces are described in the next chapter.

#include <string> using namespace std; char c = 'a'; string s = "Hello, World!";

We can transform values between the types by stating the new type within parentheses. The process of transforming a value from one type to another is called casting or type conversions.

int i = 123; double x = 1.23; int j = (int) x; double y = (double) i;

Constants

As the name implies, a constant is a variable whose value cannot be altered once it has been initialized. Unlike variables, constants must always be initialized. Constants are often written in capital letters.

Input and Output

In order to write to the standard output (normally a text window) and read from standard input (normally the keyboard), we use streams. A stream can be thought of as a connection between our program and a device such as the screen or keyboard. There are predefined objects cin and cout

that are used for input and output. We use the stream operators >> and << to write to and read from a device. Similarily to the strings above, we have to include the header file iostream and use the namespace std.

We can write and read values of all the types we have gone through so far, even though the logical values true and false are read and written as one and zero. The predefined object endl represents a new line.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

void main()

{

int i;

double x;

bool b;

string s;

cin >> i >> x >> b >> s;

cout << "You wrote i: " << i << ", x: " << x << ", b: " << b

<< ", s: " << s << endl;

}

Enumerations

An enumeration is a way to create our own integral type. We can define which values a variable of the type can store. In practice, however, enumerations are essentially an easy way to define constants.

enum Cars {FORD, VOLVO, TOYOTA, VOLKSWAGEN};

Unless we state otherwise, the constants are assigned to zero, one, two, and so on. In the example above, FORD is an integer constant with the value zero, VOLVO has the value one, TOYOTA three, and VOLKSWAGEN four.

We do not have to name the enumeration type. In the example above, Cars can be omitted. We can also assign an integer value to some (or all) of the constants. In the example below, TOYOTA is assigned the value 10. The constants without assigned values will be given the value of the preceding constant before, plus one. This implies that VOLKSWAGEN will be assigned the value 11.

enum {FORD, VOLVO, TOYOTA = 10, VOLKSWAGEN};

Arrays

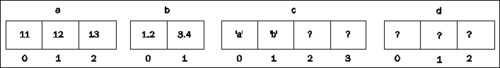

An array is a variable compiled by several values of the same type. The values are stored on consecutive locations in memory. An array may be initialized or uninitiated. An uninitiated array must always be given a size. In the following example, b is given the size 2 and c is given the size 4, even though only its first two values are defined, which may cause the compiler to emit a warning.

int a[3] = {11, 12, 13};

double b[2] = {1.2, 3.4};

char c[4] = {'a', 'b'}, d[3];

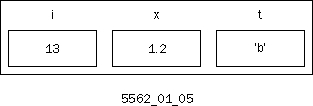

A value of an array can be accessed by index notation.

int i = a[2]; double x = b[0]; char t = c[1];

Pointers and References

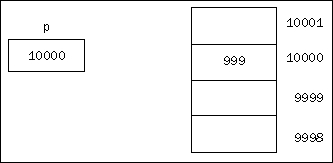

A pointer is a variable containing the address of value. Let us say that the integer i has the value 999 which is stored at the memory address 10,000. If p is a pointer to i, it holds the value 10,000.

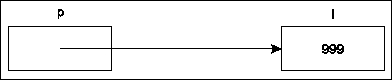

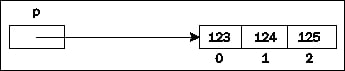

A clearer way to illustrate the same thing is to draw an arrow from the pointer to the value.

In almost all cases, we do not really need to know the address of the value. The following code gives rise to the diagram above, where the ampersand (&) denotes the address of the variable.

int i = 999; int *p = &i;

If we want to access the value pointed at, we use the asterisk (*), which derefers the pointer, «following the arrow». The address (&) and the dereferring (*) operator can be regarded as each others reverses. Note that the asterisk is used on two occasions, when we define a pointer variable and when we derefer a pointer. The asterisk is in fact used on a third occasion, when multiplying two values.

int i = 999; int *p = &i; int j = *p; // 999

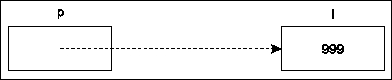

A reference is a simplified version of a pointer; it can be regarded as a constant form of a pointer. A reference variable must be initialized to refer to a value and cannot be changed later on. A reference is also automatically dereferred when we access its value. Neither do we need to state the address of the value the reference variable is initialized to refer to. The address-of (&) and dereferring (*) operators are only applicable to pointers, not to references. Note that the ampersand has two different meanings. It used as a reference marker as well as to find the address of an expression. In fact, it is also used as the bitwise and operator. A reference is usually drawn with a dashed line in order to distinguish it from a pointer.

int i = 999; int &r = i; int j = r; // 999

Pointers and Dynamic Memory

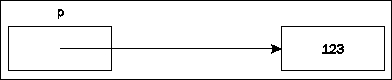

Pointers (but not references) can also be used to allocate dynamic memory. There is a section of the memory called the heap that is used for dynamically allocated memory blocks. The operators new and delete are used to allocate and deallocate the memory. Memory not dynamically allocated is referred to as static memory.

int *p = new int; *p = 123; delete p;

We can also allocate memory for a whole array. Even though p is a pointer in the example below, we can use the array index notation to access a value of the array in the allocated memory block. When we deallocate the array, we have to add a pair of brackets for the whole memory block of the array to be deallocated. Otherwise, only the memory of the first value of the array would be deallocated.

int *p = new int[3]; p[0] = 123; p[1] = 124; p[2] = 125; delete [] p;

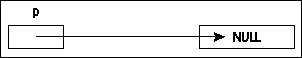

The predefined constant NULL (defined in the header file cstdlib) holds the pointer equivalence of the zero value. We say that the pointer is set to null. In the diagram, we simply write NULL.

#include <cstdlib> // ... int *p = NULL;

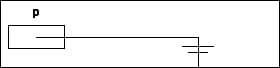

Sometimes, the electric ground symbol is used to symbolize a null pointer. For this reason, a null pointer is said to be a grounded pointer.

There is a special type void. It is not really a type, it is rather used to indicate the absence of a type. We can define a pointer to void. We can, however, not derefer the pointer. It is only useful in low-level applications where we want to examine a specific location in memory.

void* pVoid = (void*) 10000;

The void type is also useful to mark that a function does not return a value, see the function section later in this chapter.

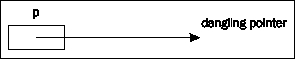

In the example below, the memory block has been deallocated, but p has not been set to null. It has become a dangling pointer; it is not null and does not really point at anything. In spite of that, we try to access the value p points at. That is a dangerous operation and would most likely result in a run-time error.

int *p = new int; *p = 1; delete p; *p = 2

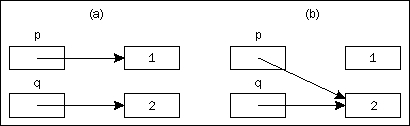

In the example below, we allocate memory for two pointers, p and q. Then we assign p to q, by doing so we have created a memory leak. There is no way we can access or deallocate the memory block that was pointed at by p. In fact, we deallocate the same memory block twice as both pointers by then point at the same memory block. This dangerous operation will most likely also result in a run-time error.

int *p = new int; // (a) int *q = new int; *p = 1; *q = 2; p = q; // (b) delete p; // Deallocates the same memory block twice, as p delete q; // and q point at the same memory block.

As a reference variable must be initialized to refer to a value and it cannot be changed, it is not possible to handle dynamic memory with references. Nor can a reference take the value null.

If we continue to allocate dynamic memory from the heap, it will eventually run out of memory. There are two ways to handle that problem. The simplest one is to mark the new call with nothrow (defined in namespace std). In that case, new will simply return a null pointer when it is out of memory.

const int BLOCK_SIZE = 0x7FFFFFFF;

void* pBlock = new (nothrow) char[BLOCK_SIZE];

if (pBlock != NULL)

{

cout << "Ok.";

// ...

delete [] pBlock;

}

else

{

cout << "Out of memory.";

}

The other way is to omit the nothrow marker. In that case, the new call will throw the exception bad_alloc in case of memory shortage. We can catch it with a try-catch block.

using namespace std;

const int BLOCK_SIZE = 0x7FFFFFFF;

try

{

void* pBlock = new char[BLOCK_SIZE];

cout << "Ok.";

// ...

delete [] pBlock;

}

catch (bad_alloc)

{

cout << "Out of memory.";

}

See the next chapter for more information on exceptions and namespaces.

Defining Our Own Types

It is possible to define our own type with typedef, which is a great tool for increasing the readability of the code. However, too many defined types tend to make the code less readable. Therefore, I advise you to use typedef with care.

int i = 1; typedef unsigned int unsigned_int; unsigned_int u = 2; typedef int* int_ptr; int_ptr ip = &i; typedef unsigned_int* uint_ptr; uint_ptr up = &u;

The Size and Limits of Types

T

he operator sizeof gives us the size of a type (the size in bytes of a value of the type) either by taking the type surrounded by parentheses or by taking a value of the type. The size of a character is always one byte and the signed and unsigned forms of each integral type always have the same size. Otherwise, the sizes are implementation-dependent. Therefore, there are predefined constants holding the minimum and maximum values of the integral and floating types. The operator returns a value of the predefined type size_t. Its exact definition is implementation-dependent. However, it is often an unsigned integer.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

#include <climits> // The integral type limit constants.

#include <cfloat> // The floating type limit constants.

void main()

{

int iIntSize1 = sizeof (int);

int iIntSize2 = sizeof iIntSize1;

cout << "integer size: " << iIntSize1 << " " << iIntSize2

<< endl;

int* pSize = &iIntSize1;

int iPtrSize = sizeof pSize;

cout << "pointer size: " << iPtrSize << endl;

int array[3] = {1, 2, 3};

int iArraySize = sizeof array;

cout << "array size: " << iArraySize << endl << endl;

cout << "Minimum signed char: " << SCHAR_MIN << endl;

cout << "Maximum signed char: " << SCHAR_MAX << endl;

cout << "Minimum signed short int: " << SHRT_MIN << endl;

cout << "Maximum signed short int: " << SHRT_MAX << endl;

cout << "Minimum signed int: " << INT_MIN << endl;

cout << "Maximum signed int: " << INT_MAX << endl;

cout << "Minimum signed long int: " << LONG_MIN << endl;

cout << "Maximum signed long int: " << LONG_MAX << endl

<< endl;

// The minimum value of an unsigned integral type is always

// zero.

cout << "Maximum unsigned char: " << UCHAR_MAX << endl;

cout << "Maximum unsigned short int: " << USHRT_MAX << endl;

cout << "Maximum unsigned int: " << UINT_MAX << endl;

cout << "Maximum unsigned long int: " << ULONG_MAX << endl

<< endl;

// There are no constants for long double.

cout << "Minimum float: " << FLT_MIN << endl;

cout << "Maximum float: " << FLT_MAX << endl;

cout << "Minimum double: " << DBL_MIN << endl;

cout << "Maximum double: " << DBL_MAX << endl;

}

Hungarian Notation

In order to identify a variable’s type and thereby increase the readability of the code, naming them in accordance with the Hungarian Notation is a good idea. The name of a variable has one or two initial small letters representing its type. The notation is named after Microsoft programmer Charles Simonyi, who was born in Budapest, Hungary.

|

Letter(s) |

Type |

Example |

|---|---|---|

|

i |

int |

int iNum; |

|

d |

double |

double dValue; |

|

c |

char |

char cInput; |

|

u |

UINT (unsigned integer) |

UINT uFlags; |

|

x |

int, the variable is a position in the x direction. |

int xPos; |

|

y |

int, the variable is a position in the y direction. |

int yPos; |

|

cx |

int, the variable is a size in the x direction. |

int cxSize; |

|

cy |

int, the variable is a size in the y direction. |

int cySize; |

|

st |

string |

string stName; |

|

cr |

COLORREF |

COLORREF crText; |

|

lf |

LOGFONT |

LOGFONT lfCurrFont; |

Objects of some common classes have in the same manner two initial small letters representing the class. Note that the C++ class string and the MFC class CString have the same initial letters. However, the C++ string class will not be used in the MFC applications of this book.

|

Letters |

Class |

Example |

|---|---|---|

|

st |

CString |

CString stBuffer; |

|

pt |

CPoint |

CPoint ptMouse; |

|

sz |

CSize |

CSize szText; |

|

rc |

CRect |

CRect rcClip; |

A pointer to an object has the initial p.

Expressions and Operators

The operations of C++ are divided into the arithmetic, relational, logical, and bitwise operators as well as simple and compound assignment. Moreover, there is the conditional operator.

In the figure below, + is an operator, a and b are operands, and the whole term is an expression.

Arithmetic Operators

The arithmetic operators are addition (+), subtraction (-), multiplication (*), division (/), and modulo (%). The first four operators are equivalent to the four fundamental rules of arithmetic. The operators can take operands of integral and floating types. The last operator—modulo—gives the remainder of integer division. If we mix integral and floating types in the expression, the result will have floating type. The modulo operator, however, can only have integral operands. The last assignment in the following code may give rise to a compiler warning as the result of the division is a double and is converted into an int.

int a = 10, b = 3, c; c = a + b; // 13 c = a - b; // 7 c = a * b; // 30 c = a / b; // 3, integer division c = a % 3; // 1, remainder double d = 3.0; c = a / d; // 3.333, floating type

Pointer Arithmetic

The addition and subtraction operators are also applicable to pointers. It is called pointer arithmetic. An integral value can be added to or subtracted from a pointer. The value of the pointer is then changed by the integral value times the size of the type the pointer points at. As the void type is not really a type, but rather the absence of a type, it has no size. Therefore, we cannot perform pointer arithmetic on pointers to void.

In the code below, let us assume that iNumber is stored at memory location 10,000 and that the integer type has the size of four bytes. Then the pointer pNumber will assume the values 10,000, 10,004, 10,008, and 10,012, not the values 10,000, 10,002, 10,003, and 10,013, as pointer arithmetic always take the size of the type into consideration.

int iNumber = 100; int* pNumber = &iNumber; pNumber = pNumber + 1; *pNumber = iNumber + 1; pNumber = pNumber + 1; *pNumber = iNumber + 2; pNumber = pNumber + 1; *pNumber = iNumber + 3;

It is also possible to subtract two pointers pointing at the same type. The result will be the difference in bytes between their two memory locations divided by the size of the type.

int array[] = {1, 2, 3};

int* p1 = &array[0];

int* p2 = &array[2];

int iDiff = p2 - p1; // 2

The index notation for arrays is equivalent to the dereferring of pointers together with pointer arithmetic. The second and third lines of the following code are by definition interchangeable.

int array[] = {1, 2, 3};

array[1] = array[2] + 1;

*(array + 1) = *(array + 2) + 1;

Increment and Decrement

T

here are two special operators: increment (++) and decrement (—). They add one to or subtract one from its operand. The operator can be placed before (prefix) or after (postfix) its operand.

int a = 1, b = 1; ++a; // 2, prefix increment b++; // 2, postfix increment

However, there is a difference between prefix and postfix increment/decrement. In the prefix case, the subtraction occurs first and the new value is returned; in the postfix case, the original value is returned after the subtraction.

int a = 1, b = 1, c, d; c = --a; // c = 0, prefix decrement d = b--; // d = 1, postfix decrement

Relational Operators

There are six relational operators: equal to (==), not equal to (!=), less than (<), less than or equal to (<=), greater than (>), and greater than or equal to (>=). Note that the equal to operator is constituted by two equals signs rather than one (one equals sign represents the assignment operator). The operators give a logical value, true or false. The operands shall be of integral or floating type.

int i = 3; double x = 1.2; bool b = i > 0; // true bool c = x == 2; // false

Logical Operators

There are three logical operators: not (!), or (||), and and (&&). They take and return logical values of the boolean type.

int i = 3; bool b, c, d, e; b = (i == 3); // true c = !b; // false d = b || c; // true e = b && c; // false

C++ applies lazy (also called short-circuit) evaluation, which means that it will not evaluate more parts of the expression than is necessary to evaluate its value. In the following example, the evaluation of the expression is completed when the left expression (i != 0) is evaluated to false. If the left expression is false, the whole expression must also be false because it needs both the left and right expressions to be true for the whole expression to be true. This shows that the right expression (1 / i == 1) will never be evaluated and the division with zero will never occur.

int i = 0; bool b = (i != 0) && (1 / i == 1); // false;

Bitwise Operators

An integer value can be viewed as a bit pattern. Our familiar decimal system has the base ten; it can be marked with an index 10.

23410=>2.100+3.10+4.1=2.102+3.101+4.100

An integer value can also be viewed with the binary system, it has the base two. A single digit viewed with the base two is called a bit, and the integer value is called a bit pattern. A bit may only take the values one and zero.

10102=>1.23+0.22+1.21+0.20=1.8+0.4+1.2+0.1=8+2=0

There are four bitwise operations in C++: inverse (~), and (&), or (|), and exclusive or (^). Exclusive or means that the result is one if one of its operand bits (but not both) is one. They all operate on integral values on bit level; that is, they examine each individual bit of an integer value.

101010102 101010102 101010102 & 100101102 | 100101102 ^ 100101102 ~ 100101102 ----------- ------------ ------------ ------------ = 100000102 = 101111102 = 001111002 = 011010012 int a = 170; // 101010102 int b = 150; // 100101102 int c = a & b; // 100000102 = 13010 int d = a | b; // 101111102 = 19010 int e = a ^ b; // 001111002 = 6010 int f = ~b; // 011010012 = 10510

An integer value can also be shifted to the left (<<) or to the right (>>). Do not confuse these operators with the stream operators; they are different operators that happen to be represented by the same symbols. Each left shift is equivalent to doubling the value, and each right shift is equivalent to (integer) dividing the value by two. Overflowing bits are dropped for unsigned values; the behavior of signed values is implementation-dependent.

unsigned char a = 172; // 10101100, base 2

unsigned char b = a << 2; // 10110000, base 2 = 160, base 10

unsigned char c = 166; // 10100110, base 2

unsigned char d = c >> 2; // 00101001, base 2 = 41, base 10

cout << (int) a << " " << (int) b << " " << (int) c << " "

<< (int) d << endl;

Assignment

There are two kinds of assignment operators: simple and compound. The simple variant is quite trivial, one or more variables are assigned the value of an expression. In the example below, a, b, and c are all assigned the value 123.

int a, b, c, d = 123; a = d; b = c = d;

The compound variant is more complicated. Let us start with the additional assignment operator. In the example below, a‘s value is increased by the value of b; that is, a is given the value 4.

int a = 2, b = 4, c = 2; a += c; // 4, equivalent to a = a + c. b -= c; // 2, equivalent to a = a - c.

In a similar manner, there are operations -=, *=, /=, %=, |=, &=, and ^= as well as |=, &=, ^=, <<=, and >>=.

The Condition Operator

The condition operator resembles the if-else statement of the next section. It is the only C++ operator that takes three operands. The first expression is evaluated. If it is true, the second expression is evaluated and its value is returned. If the first expression instead is false, the third expression is evaluated and its value is returned.

int a = 1, b = 2, max; max = (a > b) ? a : b; // The maximal value of a and b.

Too frequent use of this operator tends to make the code compact and hard to read. A piece of advice is that to restrict your use of the operator to the trivial cases.

Precedence and Associativity

Given the expression 1 + 2 * 5, what is its value? It is 11 because we first multiply two with five and then add one. We say that multiplication has a higher precedence than addition.

What if we limit ourselves to one operator, let us pick subtraction. What is the value of the expression 8 – 4 – 2? As we first subtract four from eight and then subtract two, the result is two. As we evaluate the value from left to right, we say that subtraction is left associative.

Below follows a table showing the priorities and associativities of the operator of C++. The first operator in the table has the highest priority.

|

Group |

Operators |

Associatively |

|---|---|---|

|

Brackets and fields |

() [] -> . |

Left to Right |

|

Unary operator |

! ~ ++ — + — (type) sizeof |

Right to Left |

|

Arithmetic operators |

* / % + — |

Left to Right Left to Right |

|

Shift- and streamoperators |

<< >> |

Left to Right |

|

Relation operators |

< <= > >= == != |

Left to Right |

|

Bitwise operators |

& ^ | |

Left to Right |

|

Logical operators |

&& || |

Left to Right |

|

Conditional operator |

?: |

Right to Left |

|

Assignment operators |

= += -= */ /= %= &= ^= |= <<= >>= |

Right to Left |

|

Comma operator |

, |

Left to Right |

Note that unary +, -, and * have higher priority than their binary forms. Also note that we can always change the evaluation order of an expression by inserting brackets at appropriate positition. The expression (1 + 2) * 5 has the value 15.

Statements

There are four kinds of statements in C++ : selection, iteration, jump, and expression.

|

Group |

Statements |

|---|---|

|

Selection |

|

|

Iteration |

|

|

Jump |

|

|

Expression |

|

Selection Statements

The if statement needs, in its simplest form, a logical expression to decide whether to execute the statement following the if statement or not. The example below means that the text will be output if i is greater than zero.

if (i > 0)

{

cout << "i is greater then 0";

}

We can also attach an else part, which is executed if the expression is false.

if (i > 0)

{

cout << "i is greater then zero";

}

else

{

cout << "i is not greater than zero";

}

Between the if and else part we can insert one or more else if part.

if (i > 0)

{

cout << "i is greater then zero";

}

else if (i == 0)

{

cout << "i is equal to zero";

}

else

{

cout << "i is less than zero";

}

In the examples above, it is not strictly necessary to surround the output statements with brackets. However, it would be necessary in the case of several statements.In this book, brackets are always used. The brackets and the code in between is called a block.

if (i > 0)

{

int j = i + 1;

cout << "j is " << j;

}

A warning may be in order. In an if statement, it is perfectly legal to use one equals sign instead of two when comparing two values. As one equals sign is used for assignment, not comparison, the variable i in the following code will be assigned the value one, and the expression will always be true.

if (i = 1) // Always true.

{

// ...

}

One way to avoid the mistake is to swap the variable and the value. As a value can be compared but not assigned, the compiler will issue an error message if you by mistake enter one equals sign instead of two signs.

if (1 = i) // Compile-time error.

{

// ...

}

The switch statement is simpler than the if statement, and not as powerful. It evaluates the switch value and jumps to a case statement with the same value. If no value matches, it jumps to the default statement, if present. It is important to remember the break statement. Otherwise, the execution would simply continue with the code attached to the next case statement. The break statement is used to jump out of a switch or iteration statement. The switch expression must have an integral or pointer type and two case statements cannot have the same value. The default statement can be omitted, and we can only have one default alternative. However, it must not be placed at the end of the switch statement, even though it is considered good practice to do so.

switch (i)

{

case 1:

cout << "i is equal to 1" << endl;

break;

case 2:

cout << "i is equal to 2" << endl;

break;

case 3:

cout << "i is equal to 3" << endl;

int j = i + 1;

cout << "j = " << j;

break;

default:

cout << "i is not equal to 1, 2, or 3." << endl;

break;

}

In the code above, there will be a warning for the introduction of the variable j. As a variable is valid only in its closest surrounding scope, the following code below will work without the warning.

switch (i)

{

// ...

case 3:

cout << "i is equal to 3" << endl;

{

int j = i + 1;

cout << "j = " << j;

}

break;

// ...

}

We can use the fact that an omitted break statement makes the execution continue with the next statement to group several case statements together.

switch (i)

{

case 1:

case 2:

case 3:

cout << "i is equal to 1, 2, or 3" << endl;

break;

// ...

}

Iteration Statements

Iteration statements iterate one statement (or several statements inside a block) as long as certain condition is true. The simplest iteration statement is the while statement. It repeats the statement as long as the given expression is true. The example below writes the numbers 1 to 10.

int i = 1;

while (i <= 10)

{

cout << i;

++i;

}

The same thing can be done with a do-while statement.

int i = 1;

do

{

cout << i;

++i;

}

while (i <= 10);

The do-while statement is less powerful. If the expression is false at the beginning, the while statement just skips the repetitions altogether, but the do-while statement must always execute the repetition statement at least once in order to reach the continuation condition.

We can also use the for statement, which is a more compact variant of the while statement. It takes three expressions, separated by semicolons. In the code below, the first expression initializes the variable, the repetition continues as long as the second expression is true, and the third expression is executed at the end of each repetition.

for (int i = 1; i <= 10; ++i)

{

cout << i;

}

Similar to the switch statement, the iteration statements can be interrupted by the break statement.

int i = 1;

while (true)

{

cout << i;

++i;

if (i > 10)

{

break;

}

}

Another way to construct an eternal loop is to omit the second expression of a for statement.

for (int i = 1; ; ++i)

{

cout << i;

if (i > 10)

{

break;

}

}

An iteration statement can also include a continue statement. It skips the rest of the current repetition. The following example writes the numbers 1 to 10 with the exception of 5.

for (int i = 1; i <= 10; ++i)

{

if (i == 5)

{

continue;

}

cout << i;

}

The following example, however, will not work. Because the continue statement will skip the rest of the while block, i will never be updated, and we will be stuck in an infinite loop. Therefore, I suggest you use the continue statement with care.

int i = 1;

while (i <= 10)

{

if (i == 5)

{

continue;

}

cout << i;

++i;

}

Jump Statements

We can jump from one location to another inside the same function block by marking the latter location with a label inside the block with the goto statement.

int i = 1;

label: cout << i;

++ i;

if (i <= 10)

{

goto label;

}

The goto statement is, however, considered to give rise to unstructured code, so called «spaghetti code». I strongly recommend that you avoid the goto statement altogether.

Expression Statements

An expression can form a statement.

a = b + 1; // Assignment operator. cout << "Hello, World!"; // Stream operator. WriteNumber(5); // Function call.

In the above examples, we are only interested in the side effects; that a is assigned a new value or that a text or a number is written. We are allowed to write expression statements without side effects; even though it has no meaning and it will probably be erased by the compiler.

Functions

A function can be compared to a black box. We send in information (input) and we receive information (output). In C++, the input values are called parameters and the output value is called a return value. The parameters can hold every type, and the return value can hold every type except the array.

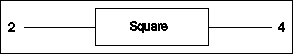

To start with, let us try the function Square. This function takes an integer and returns its square.

int Square(int n)

{

return n * n;

}

void main()

{

int i = Square(3); // Square returns 9.

}

In the example above, the parameter n in Square is called a formal parameter, and the value 3 in Square called in main is called an actual parameter.

Let us try a more complicated function, SquareRoot takes a value of double type and returns its square root. The idea is that the function iterates and calculates increasingly better root values by taking the mean value of the original value divided with the current root value and the previous root value. The process continues until the difference between two consecutive root values has reached an acceptable tolerance. Just like main, a function can have local variables. dRoot and dPrevRoot hold the current and previous value of the root, respectively.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

double SquareRoot(double dValue)

{

const double EPSILON = 1e-12;

double dRoot = dValue, dOldRoot = dValue;

while (true)

{

dRoot = ((dValue / dRoot) + dRoot) / 2;

cout << dRoot << endl;

if ((dOldRoot - dRoot) <= EPSILON)

{

return dRoot;

}

dOldRoot = dRoot;

}

}

void main()

{

double dInput = 16;

cout << "SquareRoot of " << dInput << ": "

<< SquareRoot(dInput) << endl;

}

Void Functions

A function does not have to return a value. If it does not, we set void as the return type. As mentioned above, void is used to state the absence of a type rather than a type. We can return from a void function by just stating return without a value.

void PrintSign(int iValue)

{

if (iValue < 0)

{

cout << "Negative.";

return;

}

if (iValue > 0)

{

cout << "Positive.";

return;

}

cout << "Zero";

}

There is no problem if the execution of a void function reaches the end of the code, it just jumps back to the calling function. However, a non-void function shall always return a value before reaching the end of the code. The compiler will give a warning if it is possible to reach the end of a non-void function.

Local and Global Variables

There are four kinds of variables. Two of them are local and global variables, which we consider in this section. The other two kinds of variables are class fields and exceptions, which will be dealt with in the class and exception sections of the next chapter.

A global variable is defined outside a function and a local variable is defined inside a function.

int iGlobal = 1;

void main()

{

int iLocal = 2;

cout << "Global variable: " << iGlobal // 1

<< ", Local variable: " << iLocal // 2

<< endl;

}

A global and a local variable can have the same name. In that case, the name in the function refers to the local variable. We can access the global variable by using two colons (::).

int iNumber = 1;

void main()

{

int iNumber = 2;

cout << "Global variable: " << ::iNumber // 1

<< ", Local variable: " << iNumber; // 2

}

A variable can also be defined in an inner block. As a block may contain another block, there may be many variables with the same name in the same scope. Unfortunately, we can only access the global and the most local variable. In the inner block of the following code, there is no way to access iNumber with value 2.

int iNumber = 1;

void main()

{

int iNumber = 2;

{

int iNumber = 3;

cout << "Global variable: " << ::iNumber // 1

<< ", Local variable: " << iNumber; // 3

}

}

Global variables are often preceded by g_ in order to distinguish them from local variables.

int g_iNumber = 1;

void main()

{

int iNumber = 2;

cout << "Global variable: " << g_iNumber // 1

<< ", Local variable: " << iNumber; // 3

}

Call-by-Value and Call-by-Reference

Say that we want to write a function for switching the values of two variables.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void Swap(int iNumber1, int iNumber2)

{

int iTemp = iNumber1; // (a)

iNumber1 = iNumber2; // (b)

iNumber2 = iTemp; // (c)

}

void main()

{

int iNum1 = 1, iNum2 = 2;

cout << "Before: " << iNum1 << ", " << iNum2 << endl;

Swap(iNum1, iNum2);

cout << "After: " << iNum1 << ", " << iNum2 << endl;

}

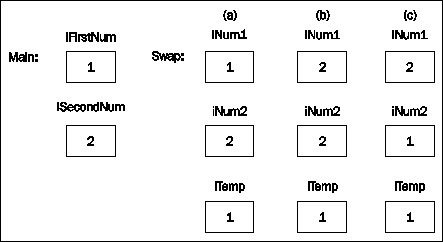

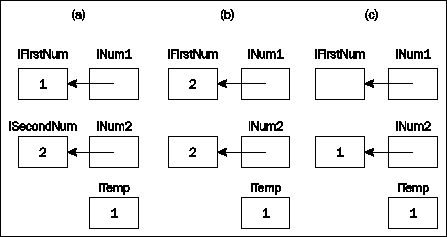

Unfortunately, this will not work; the variables will keep their values. The explanation is that the values of iFirstNum and iSecondNum in main are copied into iNum1 and iNum2 in Swap. Then iNum1 and iNum2 exchange values with the help if iTemp. However, their values are not copied back into iFirstNum and iSecondNum in main.

The problem can be solved with reference calls. Instead of sending the values of the actual parameters, we send their addresses by adding an ampersand (&) to the type. As you can see in the code, the Swap call in main is identical to the previous one without references. However, the call will be different.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void Swap(int& iNum1, int& iNum2)

{

int iTemp = iNum1; // (a)

iNum1 = iNum2; // (b)

iNum2 = iTemp; // (c)

}

void main()

{

int iFirstNum = 1, iSecondNum = 2;

cout << "Before: " << iFirstNum << ", " << iSecondNum

<< endl;

Swap(iFirstNum, iSecondNum);

cout << "After: " << iFirstNum << ", " << iSecondNum

<< endl;

}

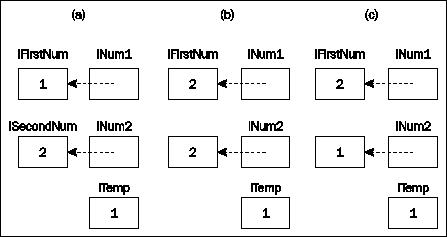

In this case, we do not send the values of iFirstNum and iSecondNum, but rather their addresses. Therefore, iNum1 and iNum2 in Swap does in fact contain the addresses of iFirstNum and iSecondNum of main. As in the reference section above, we illustrate this with dashed arrows. Therefore, when iNum1 and iNum2 exchange values, in fact the values of iFirstNum and iSecondNum are exchanged.

A similar effect can be obtained with pointers instead of references. In that case, however, both the definition of the function as well as the call from main are different.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void Swap(int* pNum1, int* pNum2)

{

int iTemp = *pNum1; // (a)

*pNum1 = *pNum2; // (b)

*pNum2 = iTemp; // (c)

}

void main()

{

int iFirstNum = 1, iSecondNum = 2;

cout << "Before: " << iFirstNum << ", " << iSecondNum

<< endl;

Swap(&iFirstNum, &iSecondNum);

cout << "After: " << iFirstNum << ", " << iSecondNum

<< endl;

}

In this case, pNum1 and pNum2 are pointers, and therefore drawn with continuous lines. Apart from that, the effect is the same.

Default Parameters

A

default parameter is a parameter that will be given a specific value if the call does not include its value. In the example below, all three calls are legitimate. In the first call, iNum2 and iNum3 will be given the values 9 and 99, respectively; in the second call, iNum3 will be given the value 99. Default values can only occur from the right in the parameter list; when a parameter is given a default value, all the following parameters must also be given default values.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int Add(int iNum1, int iNum2 = 9, int iNum3 = 99)

{

return iNum1 + iNum2 + iNum3;

}

void main()

{

cout << Add(1) << endl; // 1 + 9 + 99 = 109

cout << Add(1, 2) << endl; // 1 + 2 + 99 = 102

cout << Add(1, 2 ,3) << endl; // 1 + 2 + 3 = 6

}

Overloading

Several different functions may be overloaded, which means that they may have the same name as long as they do not share exactly the same parameter list. C++ supports context-free overloading, the parameter lists must differ, it is not enough to let the return types differ. The languages Ada and Lisp support context-dependent overloading, two functions may have the same name and parameter list as long as they have different return types.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int Add(int iNum1)

{

return iNum1;

}

int Add(int iNum1, int iNum2)

{

return iNum1 + iNum2;

}

int Add(int iNum1, int iNum2, int iNum3)

{

return iNum1 + iNum2 + iNum3;

}

void main()

{

cout << Add(1) << endl; // 1

cout << Add(1, 2) << endl; // 1 + 2 = 3

cout << Add(1, 2 ,3) << endl; // 1 + 2 + 3 = 6

}

Static Variables

In the function below, iCount is a static local variable, which means that it is initialized when the execution of the program starts. It is not initialized when the function is called.

void KeepCount()

{

static int iCount = 0;

++iCount;

cout << "This function has been called " << iCount

<< "times." << endl;

}

If iCount was a regular local variable (without the keyword static), the function would at every call write that the function has been called once as iCount would be initialized to zero at every call.

The keyword static can, however, also be used to define functions and global variables invisible to the linker and other object files.

Recursion

A function may call itself; it is called recursion. In the following example, the mathematical function factorial (n!) is implemented. It can be defined in two ways. The first definition is rather straightforward. The result of the function applied to a positive integer n is the product of all positive integers up to and including n.

int Factorial(int iNumber)

{

int iProduct = 1;

for (int iCount = 1; iCount <= iNumber; ++iCount)

{

iProduct *= iCount;

}

return iProduct;

}

An equivalent definition involves a recursive call that is easier to implement.

int Factorial(int iNumber)

{

if (iNumber == 1)

{

return 1;

}

else

{

return iNumber * Factorial(iNumber - 1);

}

}

Definition and Declaration

It’

s important to distinguish between the terms definition and declaration. For a function, its definition generates code while the declaration is merely an item of information to the compiler. A function declaration is also called a prototype.

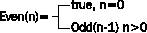

When it comes to mutual recursion (two functions calling each other), at least the second of them must have a prototype to avoid compiler warnings. I recommend that you put prototypes for all functions at the beginning of the file. In the following example, we use two functions to decide whether a given non-negative integer is even or odd according to the following definitions.

bool Even(int iNum);

bool Odd(int iNum);

bool Even(int iNum)

{

if (iNum == 0)

{

return true;

}

else

{

return Odd(iNum - 1);

}

}

bool Odd(int iNum)

{

if (iNum == 0)

{

return false;

}

else

{

return Even(iNum - 1);

}

}

If we use prototypes together with default parameters, we can only indicate the default value in the prototype, not in the definition.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int Add(int iNum1, int iNum2 = 9, int iNum3 = 99);

void main()

{

cout << Add(1) << endl; // 1 + 9 + 99 = 109

}

int Add(int iNum1, int iNum2 /* = 9 */, int iNum3 /* = 99 */)

{

return iNum1 + iNum2 + iNum3;

}

Higher Order Functions

A function that takes another function as a parameter is called a higher order function. Technically, C++ does not take the function itself as a parameter, but rather a pointer to the function. However, the pointer mark (*) may be omitted. The following example takes an array of the given size and applies the given function to each integer in the array.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void ApplyArray(int intArray[], int iSize, int Apply(int))

{

for (int iIndex = 0; iIndex < iSize; ++iIndex)

{

intArray[iIndex] = Apply(intArray[iIndex]);

}

}

int Double(int iNumber)

{

return 2 * iNumber;

}

int Square(int iNumber)

{

return iNumber * iNumber;

}

void PrintArray(int intArray[], int iSize)

{

for (int iIndex = 0; iIndex < iSize; ++iIndex)

{

cout << intArray[iIndex] << " ";

}

cout << endl;

}

void main()

{

int numberArray[] = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

int iArraySize = sizeof numberArray / sizeof numberArray[0];

PrintArray(numberArray, iArraySize);

// Doubles every value in the array.

ApplyArray(numberArray, iArraySize, Double);//2,4,6,8,10

PrintArray(numberArray, iArraySize);

// Squares every value in the array.

ApplyArray(numberArray, iArraySize, Square);//4,16,36,64,100

PrintArray(numberArray, iArraySize);

}

One extra point in the example above is the method of finding the size of an array; we divide the size of the array with the size of its first value. This method only works on static arrays, not on dynamically allocated arrays or arrays given as parameters to functions. A parameter array is in fact converted to a pointer to the type of the array. The following two function definitions are by definition equivalent.

void PrintArray(int intArray[], int iSize)

{

// ...

}

void PrintArray(int* intArray, int iSize)

{

// ...

}

The main() Function

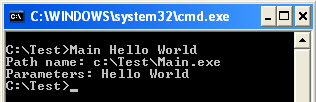

The main program is in fact a function; the only special thing about it is that it is the start point of the program execution. Just like a regular function it can have formal parameters and return a value. However, the parameter list must have a special format. The first parameter iArgCount is an integer indicating the number of arguments given by the system. The second parameter vpValues (vp stands for vector of pointers) holds the arguments. It is an array of pointers to characters, which can be interpreted as an array of strings, holding the system arguments. However, the first value of the array always holds the path name of the program. In some tutorials, the traditional parameter names argc and argv are used instead iArgCount and vpValues. The program below writes its path name and its arguments.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main(int iArgCount, char* vpValues[])

{

cout << "Path name: " << vpValues[0] << endl;

cout << "Parameters: ";

for (int iIndex = 1; iIndex < iArgCount; ++iIndex)

{

cout << vpValues[iIndex] << " ";

}

}

The arguments can be input from the command prompt.

The return value of the main function can (besides void) only be signed or unsigned int. The return value is often used to return an error code to the operating system; usually, zero indicates ok and a negative value indicates an error. The program below tries to allocate a large chunk of memory. It returns zero if it turns out well, minus one otherwise.

#include <cstdlib>

int main()

{

const int BLOCK_SIZE = 7FFFFFFF;

void* pBlock = new (nothrow) char[BLOCK_SIZE];

if (pBlock != NULL)

{

// ...

delete [] pBlock;

return 0;

}

return -1;

}

The Preprocessor

The preprocessor is a tool that precedes the compiler in interpreting the code. The #include directive is one of its parts. It opens the file and includes its text. So far, we have only included system header files, whose names are surrounded by arrow brackets (< and >). Later on, we will include our own header files. Then we will use parentheses instead of arrow brackets. The difference is that the preprocessor looks for the system header files in a special system file directory while it looks for our header files in the local file directory.

Another part of the preprocessor is the macros. There are two kinds: with or without parameters. A macro without parameters works like a constant.

#define ARRAY_SIZE 256 int arr[ARRAY_SIZE];

The predefined macros __DATE__, __TIME__, __FILE__ , and __LINE__ holds today’s date, the current time, the current line number, and the name of the file, respectively.

Macros with parameters act like functions with the difference being that they do not perform any type checking, they just replace the text. A macro is introduced with the #define directive and is often written with capitals.

#define ADD(a, b) ((a) + (b)) cout << ADD(1 + 2, 3 * 4) << endl; // 15

One useful macro is assert, it is defined in the header file cassert. It takes a logical parameter and exits the program execution with an appropriate message if the parameter is false. exit is a standard function that aborts the execution of the program and returns an integer value to the operating system. When a macro definition stretches over several lines, each line except the last one must end witha backslash.

#define assert(test)

{

if (!(test))

{

cout << "Assertion: "" << #test << "" on line "

<< __LINE__ << " in file " << __FILE__ << ".";

::exit(-1);

}

}

In the error handling section of the next chapter, we will define an error checking macro displaying the error message in a message box.

It is also possible to perform conditional programming by checking the value of macros. In the following example, we define a system integer according to the underlying operating system.

#ifdef WINDOWS #define SYSINT int #endif #ifdef LINUX #define SYSINT unsigned int #endif #ifdef MACHINTOCH #define SYSINT long int #endif SYSINT iOpData = 0;

The ASCII Table

|

0 |

nul |

26 |

sub |

52 |

4 |

78 |

N |

104 |

h |

|

1 |

soh |

27 |

esc |

53 |

5 |

79 |

O |

105 |

i |

|

2 |

stx |

28 |

fs |

54 |

6 |

80 |

p |

106 |

j |

|

3 |

etx |

29 |

gs |

55 |

7 |

81 |

Q |

107 |

k |

|

4 |

eot |

30 |

rs |

56 |

8 |

82 |

R |

108 |

l |

|

5 |

enq |

31 |

us |

57 |

9 |

83 |

S |

109 |

m |

|

6 |

ack |

32 |

blank |

58 |

: |

84 |

T |

110 |

n |

|

7 |

bel a |

33 |

! |

59 |

; |

85 |

U |

111 |

o |

|

8 |

bs b |

34 |

« |

60 |

< |

86 |

V |

112 |

p |

|

9 |

ht t |

35 |

# |

61 |

= |

87 |

W |

113 |

q |

|

10 |

lf n |

36 |

$ |

62 |

> |

88 |

X |

114 |

r |

|

11 |

vt vt |

37 |

% |

63 |

? |

89 |

Y |

115 |

s |

|

12 |

ff f |

38 |

& |

64 |

@ É |

90 |

Z |

116 |

t |

|

13 |

cr r |

39 |

‘ |

65 |

A |

91 |

[ Ä |

117 |

u |

|

14 |

soh |

40 |

( |

66 |

B |

92 |

Ö |

118 |

v |

|

15 |

si |

41 |

) |

67 |

C |

93 |

] Å |

119 |

w |

|

16 |

dle |

42 |

* |

68 |

D |

94 |

^ Ü |

120 |

x |

|

17 |

dc1 |

43 |

+ |

69 |

E |

95 |

_ |

121 |

y |

|

18 |

dc2 |

44 |

, |

70 |

F |

96 |

` é |

122 |

z |

|

19 |

dc3 |

45 |

— |

71 |

G |

97 |

a |

123 |

{ ä |

|

20 |

dc4 |

46 |

. |

72 |

H |

98 |

b |

124 |

| ö |

|

21 |

nak |

47 |

/ |

73 |

I |

99 |

c |

125 |

} å |

|

22 |

syn |

48 |

0 |

74 |

J |

100 |

d |

126 |

~ ü |

|

23 |

etb |

49 |

1 |

75 |

K |

101 |

e |

127 |

delete |

|

24 |

can |

50 |

2 |

76 |

L |

102 |

f |

||

|

25 |

em |

51 |

3 |

77 |

M |

103 |

g |

Summary

Let’s revise the points quickly in brief as discussed in this chapter:

-

The text of a program is called its source code. It is translated into target code by the compiler. The target code is then linked to target code of other programs, finally resulting in executable code.

-

The basic types of C++ can be divided into the integral types char, short int, int, and long int, and the floating types float, double, and long double. The integral types can also be signed or unsigned.

-

Values of a type can be organized into an array, which is indexed by an integer. The first index is always zero. An enum value is an enumeration of named values. It is also possible to define new types with typedef, though that feature should be used carefully.

-

A pointer holds the memory address of another value. There are operators to obtain the value pointed at and to obtain the address of a value. A reference is a simpler version of a pointer. A reference always holds the address of a specific value while a pointer may point at different values. A pointer can also be used to allocate memory dynamically; that is, during the program execution.

-

The operators can be divided into the arithmetic operators addition, subraction, multiplication, division, and modulo; the relational operators equal to, not equal to, less than, less than or equal to, greater than, and greater than or equal to; the logical operators not, and, and or; the bitwise operators inverse, and, or, and xor; the assignment operators, and the condition operator. There is also the operator sizeof, which gives the size in bytes of values of a certain type.

-

The statments of C++ can divided into the selection statements if and switch, the iteration statements while and for, and the jump statements break, continue, and goto, even thought goto should be avoided.

-

A function may take one or more formal parameters as input. When it is called, a matching list of actual parameters must be provided. A function may also return a value of arbitrary type, with the exception of array. Two functions may be overloaded, which means they have the same name, as long as they differ in their parameter lists. A function may call itself, directly or indirectly; this is called recursion. A function can also have default parameters, which means that if the caller does not provide enough parameters, the missing parameters will be given the default values.

-

A macro is a textual substitution performed by the preprocessor before the compilation of the program. Similar to functions, they may take parameters. We can also include the text of other files into our program. Finally, we can include and exclude certain parts of the code by conditional programming.

Book description

In Detail

With this book you will learn how to create applications using

MDI, complex file formats, text parsing and processing, graphics,

and interactions. Every essential skill required to build Windows

desktop–style applications is covered in the context of fully

working examples.

The book begins with a quick primer on the C++ language, and

using the Visual C++ IDE to create Windows applications. This acts

as a recap for existing C++ programmers, and a quick guide to the

language if you’ve not worked with C++ before. The book then moves

into a set of comprehensive example applications, presenting the

important parts of the code with explanation of how it works, and

how and when to use similar techniques in your own

applications.

The applications include: a Tetris-style game, a drawing

application, a spreadsheet, and a word processor.

If you know the C++ language, or another Windows-based

programming language, and want to use C++ to write real, complex

applications then this book is ideal for you.

What you will learn from this book?

When you read this book, you will learn to:

-

Build larger, more powerful, user friendly C++

applications -

Create MDI (multiple document interface) applications and use

other Windows application interface elements -

Create memory structures for complex application objects:

documents, spreadsheets, drawings -

Save files to represent these memory structures

-

Parse and process text, display interactive graphics, and

handle input from the mouse and the keyboard

Who this book is written for?

The book is ideal for programmers who have worked with C++ or

other Windows-based programming languages. It provides developers

with everything they need to build complex desktop applications

using C++.

If you have already learned the C++ language, and want to take

your programming to the next level, then this book is ideal for

you.

So far we have seen how to work with C# to create console based applications. But in a real-life scenario team normally use Visual Studio and C# to create either Windows Forms or Web-based applications.

A windows form application is an application, which is designed to run on a computer. It will not run on web browser because then it becomes a web application.

This Tutorial will focus on how we can create Windows-based applications. We will also learn some basics on how to work with the various elements of C# Windows application.

In this Windows tutorial, you will learn-

- Windows Forms Basics

- Hello World in Windows Forms

- Adding Controls to a form

- Event Handling for Controls

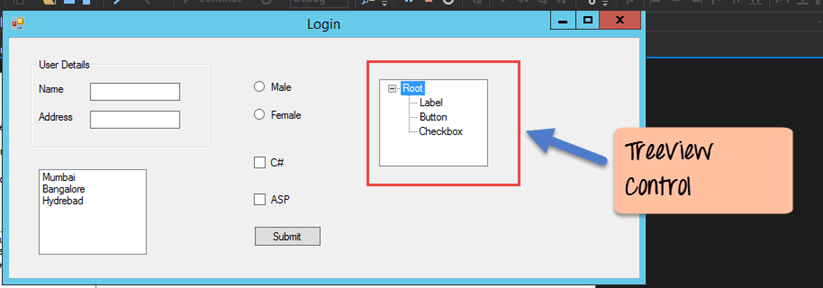

- Tree and PictureBox Control

Windows Forms Basics

A Windows forms application is one that runs on the desktop computer. A Windows forms application will normally have a collection of controls such as labels, textboxes, list boxes, etc.

Below is an example of a simple Windows form application C#. It shows a simple Login screen, which is accessible by the user. The user will enter the required credentials and then will click the Login button to proceed.

So an example of the controls available in the above application

- This is a collection of label controls which are normally used to describe adjacent controls. So in our case, we have 2 textboxes, and the labels are used to tell the user that one textbox is for entering the user name and the other for the password.

- The 2 textboxes are used to hold the username and password which will be entered by the user.

- Finally, we have the button control. The button control will normally have some code attached to perform a certain set of actions. So for example in the above case, we could have the button perform an action of validating the user name and password which is entered by the user.

C# Hello World

Now let’s look at an example of how we can implement a simple ‘hello world’ application in Visual Studio. For this, we would need to implement the below-mentioned steps

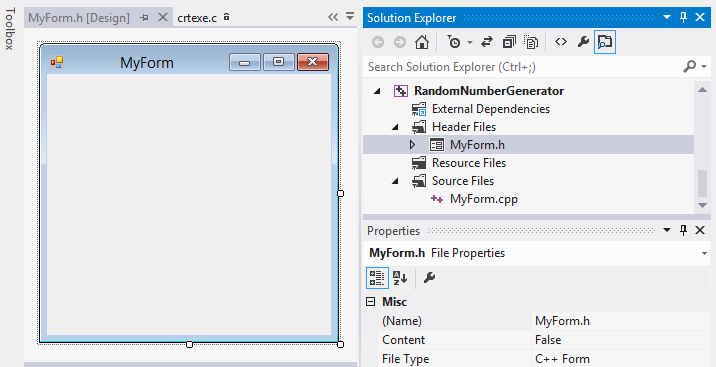

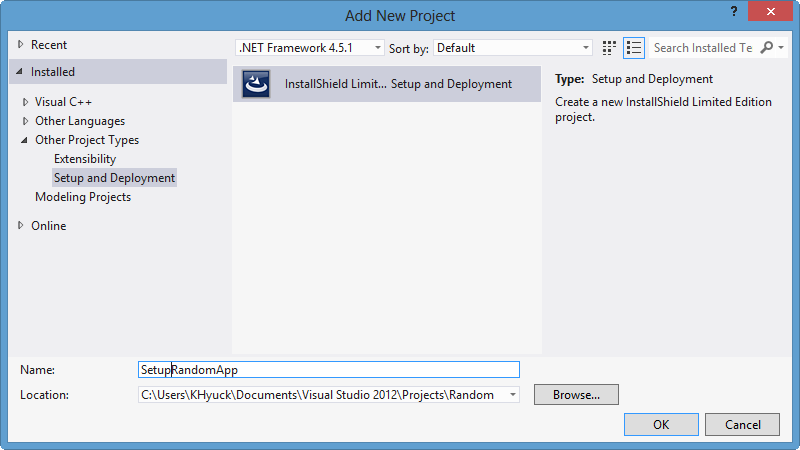

Step 1) The first step involves the creation of a new project in Visual Studio. After launching Visual Studio, you need to choose the menu option New->Project.

Step 2) The next step is to choose the project type as a Windows Forms application. Here we also need to mention the name and location of our project.

- In the project dialog box, we can see various options for creating different types of projects in Visual Studio. Click the Windows option on the left-hand side.

- When we click the Windows options in the previous step, we will be able to see an option for Windows Forms Application. Click this option.

- We will give a name for the application. In our case, it is DemoApplication. We will also provide a location to store our application.

- Finally, we click the ‘OK’ button to let Visual Studio create our project.

If the above steps are followed, you will get the below output in Visual Studio.

Output:-

You will see a Form Designer displayed in Visual Studio. It’s in this Form Designer that you will start building your Windows Forms application.

In the Solution Explorer, you will also be able to see the DemoApplication Solution. This solution will contain the below 2 project files

- A Form application called Forms1.cs. This file will contain all of the code for the Windows Form application.

- The Main program called Program.cs is default code file which is created when a new application is created in Visual Studio. This code will contain the startup code for the application as a whole.

On the left-hand side of Visual Studio, you will also see a ToolBox. The toolbox contains all the controls which can be added to a Windows Forms. Controls like a text box or a label are just some of the controls which can be added to a Windows Forms.

Below is a screenshot of how the Toolbox looks like.

Step 3) In this step, we will now add a label to the Form which will display “Hello World.” From the toolbox, you will need to choose the Label control and simply drag it onto the Form.

Once you drag the label to the form, you can see the label embedded on the form as shown below.

Step 4) The next step is to go to the properties of the control and Change the text to ‘Hello World’.

To go to the properties of a control, you need to right-click the control and choose the Properties menu option

- The properties panel also shows up in Visual Studio. So for the label control, in the properties control, go to the Text section and enter “Hello World”.

- Each Control has a set of properties which describe the control.

If you follow all of the above steps and run your program in Visual Studio, you will get the following output

Output:-

In the output, you can see that the Windows Form is displayed. You can also see ‘Hello World’ is displayed on the form.

Adding Controls to a form

We had already seen how to add a control to a form when we added the label control in the earlier section to display “Hello World.”

Let’s look at the other controls available for Windows forms and see some of their common properties.

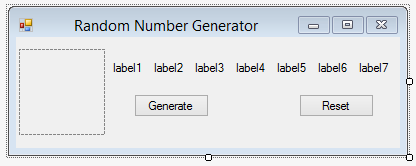

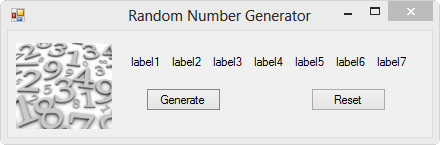

In our Windows form application in C# examples, we will create one form which will have the following functionality.

- The ability for the user to enter name and address.

- An option to choose the city in which the user resides in

- The ability for the user to enter an option for the gender.

- An option to choose a course which the user wants to learn. There will make choices for both C# and ASP.Net

So let’s look at each control in detail and add them to build the form with the above-mentioned functionality.

Group Box

A group box is used for logical grouping controls into a section. Let’s take an example if you had a collection of controls for entering details such as name and address of a person. Ideally, these are details of a person, so you would want to have these details in a separate section on the Form. For this purpose, you can have a group box. Let’s see how we can implement this with an example shown below

Step 1) The first step is to drag the Groupbox control onto the Windows Form from the toolbox as shown below

Step 2) Once the groupbox has been added, go to the properties window by clicking on the groupbox control. In the properties window, go to the Text property and change it to “User Details”.

Once you make the above changes, you will see the following output

Output:-

In the output, you can clearly see that the Groupbox was added to the form. You can also see that the text of the groupbox was changed to “User Details.”

Label Control

Next comes the Label Control. The label control is used to display a text or a message to the user on the form. The label control is normally used along with other controls. Common examples are wherein a label is added along with the textbox control.

The label indicates to the user on what is expected to fill up in the textbox. Let’s see how we can implement this with an example shown below. We will add 2 labels, one which will be called ‘name’ and the other called ‘address.’ They will be used in conjunction with the textbox controls which will be added in the later section.

Step 1) The first step is to drag the label control on to the Windows Form from the toolbox as shown below. Make sure you drag the label control 2 times so that you can have one for the ‘name’ and the other for the ‘address’.

Step 2) Once the label has been added, go to the properties window by clicking on the label control. In the properties window, go to the Text property of each label control.

Once you make the above changes, you will see the following output

Output:-

You can see the label controls added to the form.

Textbox

A textbox is used for allowing a user to enter some text on the Windows application in C#. Let’s see how we can implement this with an example shown below. We will add 2 textboxes to the form, one for the Name and the other for the address to be entered for the user

Step 1) The first step is to drag the textbox control onto the Windows Form from the toolbox as shown below

Step 2) Once the text boxes have been added, go to the properties window by clicking on the textbox control. In the properties window, go to the Name property and add a meaningful name to each textbox. For example, name the textbox for the user as txtName and that for the address as txtAddress. A naming convention and standard should be made for controls because it becomes easier to add extra functionality to these controls, which we will see later on.

Once you make the above changes, you will see the following output

Output:-

In the output, you can clearly see that the Textboxes was added to the form.

List box

A Listbox is used to showcase a list of items on the Windows form. Let’s see how we can implement this with an example shown below. We will add a list box to the form to store some city locations.

Step 1) The first step is to drag the list box control onto the Windows Form from the toolbox as shown below

Step 2) Once the list box has been added, go to the properties window by clicking on the list box control.

- First, change the property of the Listbox box control, in our case, we have changed this to lstCity

- Click on the Items property. This will allow you to add different items which can show up in the list box. In our case, we have selected items “collection”.

- In the String Collection Editor, which pops up, enter the city names. In our case, we have entered “Mumbai”, “Bangalore” and “Hyderabad”.

- Finally, click on the ‘OK’ button.

Once you make the above changes, you will see the following output

Output:-

In the output, you can see that the Listbox was added to the form. You can also see that the list box has been populated with the city values.

RadioButton

A Radiobutton is used to showcase a list of items out of which the user can choose one. Let’s see how we can implement this with an example shown below. We will add a radio button for a male/female option.

Step 1) The first step is to drag the ‘radiobutton’ control onto the Windows Form from the toolbox as shown below.

Step 2) Once the Radiobutton has been added, go to the properties window by clicking on the Radiobutton control.

- First, you need to change the text property of both Radio controls. Go the properties windows and change the text to a male of one radiobutton and the text of the other to female.

- Similarly, change the name property of both Radio controls. Go the properties windows and change the name to ‘rdMale’ of one radiobutton and to ‘rdfemale’ for the other one.

One you make the above changes, you will see the following output

Output:-

You will see the Radio buttons added to the Windows form.

Checkbox

A checkbox is used to provide a list of options in which the user can choose multiple choices. Let’s see how we can implement this with an example shown below. We will add 2 checkboxes to our Windows forms. These checkboxes will provide an option to the user on whether they want to learn C# or ASP.Net.

Step 1) The first step is to drag the checkbox control onto the Windows Form from the toolbox as shown below

Step 2) Once the checkbox has been added, go to the properties window by clicking on the Checkbox control.

In the properties window,

- First, you need to change the text property of both checkbox controls. Go the properties windows and change the text to C# and ASP.Net.

- Similarly, change the name property of both Radio controls. Go the properties windows and change the name to chkC of one checkbox and to chkASP for the other one.

Once you make the above changes, you will see the following output

Output:-

Button

A button is used to allow the user to click on a button which would then start the processing of the form. Let’s see how we can implement this with an example shown below. We will add a simple button called ‘Submit’ which will be used to submit all the information on the form.

Step 1) The first step is to drag the button control onto the Windows Form from the toolbox as shown below

Step 2) Once the Button has been added, go to the properties window by clicking on the Button control.

- First, you need to change the text property of the button control. Go the properties windows and change the text to ‘submit’.

- Similarly, change the name property of the control. Go the properties windows and change the name to ‘btnSubmit’.

Once you make the above changes, you will see the following output

Output:-

Congrats, you now have your first basic Windows Form in place. Let’s now go to the next topic to see how we can do Event handling for Controls.

C# Event Handling for Controls

When working with windows form, you can add events to controls. An event is something that happens when an action is performed. Probably the most common action is the clicking of a button on a form. In C# Windows Forms, you can add code which can be used to perform certain actions when a button is pressed on the form.

Normally when a button is pressed on a form, it means that some processing should take place.

Let’s take a look at one of the event and how it can be handled before we go to the button event scenario.

The below example will showcase an event for the Listbox control. So whenever an item is selected in the listbox control, a message box should pop up which shows the item selected. Let’s perform the following steps to achieve this.

Step 1) Double click on the Listbox in the form designer. By doing this, Visual Studio will automatically open up the code file for the form. And it will automatically add an event method to the code. This event method will be triggered, whenever any item in the listbox is selected.

Above is the snippet of code which is automatically added by Visual Studio, when you double-click the List box control on the form. Now let’s add the below section of code to this snippet of code, to add the required functionality to the listbox event.

- This is the event handler method which is automatically created by Visual Studio when you double-click the List box control. You don’t need to worry about the complexity of the method name or the parameters passed to the method.