Project description

Beautiful Soup is a library that makes it easy to scrape information

from web pages. It sits atop an HTML or XML parser, providing Pythonic

idioms for iterating, searching, and modifying the parse tree.

Quick start

>>> from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

>>> soup = BeautifulSoup("<p>Some<b>bad<i>HTML")

>>> print(soup.prettify())

<html>

<body>

<p>

Some

<b>

bad

<i>

HTML

</i>

</b>

</p>

</body>

</html>

>>> soup.find(text="bad")

'bad'

>>> soup.i

<i>HTML</i>

#

>>> soup = BeautifulSoup("<tag1>Some<tag2/>bad<tag3>XML", "xml")

#

>>> print(soup.prettify())

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<tag1>

Some

<tag2/>

bad

<tag3>

XML

</tag3>

</tag1>

To go beyond the basics, comprehensive documentation is available.

Links

- Homepage

- Documentation

- Discussion group

- Development

- Bug tracker

- Complete changelog

Note on Python 2 sunsetting

Beautiful Soup’s support for Python 2 was discontinued on December 31,

2020: one year after the sunset date for Python 2 itself. From this

point onward, new Beautiful Soup development will exclusively target

Python 3. The final release of Beautiful Soup 4 to support Python 2

was 4.9.3.

Supporting the project

If you use Beautiful Soup as part of your professional work, please consider a

Tidelift subscription.

This will support many of the free software projects your organization

depends on, not just Beautiful Soup.

If you use Beautiful Soup for personal projects, the best way to say

thank you is to read

Tool Safety, a zine I

wrote about what Beautiful Soup has taught me about software

development.

Building the documentation

The bs4/doc/ directory contains full documentation in Sphinx

format. Run make html in that directory to create HTML

documentation.

Running the unit tests

Beautiful Soup supports unit test discovery using Pytest:

$ pytest

Download files

Download the file for your platform. If you’re not sure which to choose, learn more about installing packages.

Source Distribution

Built Distribution

Beautiful Soup — это

библиотека Python для извлечения данных из файлов HTML и XML. Она работает

с вашим любимым парсером, чтобы дать вам естественные способы навигации,

поиска и изменения дерева разбора. Она обычно экономит программистам

часы и дни работы.

Эти инструкции иллюстрируют все основные функции Beautiful Soup 4

на примерах. Я покажу вам, для чего нужна библиотека, как она работает,

как ее использовать, как заставить ее делать то, что вы хотите, и что нужно делать, когда она

не оправдывает ваши ожидания.

Примеры в этой документации работают одинаково на Python 2.7

и Python 3.2.

Возможно, вы ищете документацию для Beautiful Soup 3.

Если это так, имейте в виду, что Beautiful Soup 3 больше не

развивается, и что поддержка этой версии будет прекращена

31 декабря 2020 года или немногим позже. Если вы хотите узнать о различиях между Beautiful Soup 3

и Beautiful Soup 4, читайте раздел Перенос кода на BS4.

Эта документация переведена на другие языки

пользователями Beautiful Soup:

- 这篇文档当然还有中文版.

- このページは日本語で利用できます(外部リンク)

- 이 문서는 한국어 번역도 가능합니다.

- Este documento também está disponível em Português do Brasil.

Быстрый старт¶

Вот HTML-документ, который я буду использовать в качестве примера в этой

документации. Это фрагмент из «Алисы в стране чудес»:

html_doc = """ <html><head><title>The Dormouse's story</title></head> <body> <p class="title"><b>The Dormouse's story</b></p> <p class="story">Once upon a time there were three little sisters; and their names were <a href="http://example.com/elsie" class="sister" id="link1">Elsie</a>, <a href="http://example.com/lacie" class="sister" id="link2">Lacie</a> and <a href="http://example.com/tillie" class="sister" id="link3">Tillie</a>; and they lived at the bottom of a well.</p> <p class="story">...</p> """

Прогон документа через Beautiful Soup дает нам

объект BeautifulSoup, который представляет документ в виде

вложенной структуры данных:

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup soup = BeautifulSoup (html_doc, 'html.parser') print(soup.prettify()) # <html> # <head> # <title> # The Dormouse's story # </title> # </head> # <body> # <p class="title"> # <b> # The Dormouse's story # </b> # </p> # <p class="story"> # Once upon a time there were three little sisters; and their names were # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1"> # Elsie # </a> # , # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2"> # Lacie # </a> # and # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3"> # Tillie # </a> # ; and they lived at the bottom of a well. # </p> # <p class="story"> # ... # </p> # </body> # </html>

Вот несколько простых способов навигации по этой структуре данных:

soup.title # <title>The Dormouse's story</title> soup.title.name # u'title' soup.title.string # u'The Dormouse's story' soup.title.parent.name # u'head' soup.p # <p class="title"><b>The Dormouse's story</b></p> soup.p['class'] # u'title' soup.a # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a> soup.find_all('a') # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>] soup.find(id="link3") # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>

Одна из распространенных задач — извлечь все URL-адреса, найденные на странице в тегах <a>:

for link in soup.find_all('a'): print(link.get('href')) # http://example.com/elsie # http://example.com/lacie # http://example.com/tillie

Другая распространенная задача — извлечь весь текст со страницы:

print(soup.get_text()) # The Dormouse's story # # The Dormouse's story # # Once upon a time there were three little sisters; and their names were # Elsie, # Lacie and # Tillie; # and they lived at the bottom of a well. # # ...

Это похоже на то, что вам нужно? Если да, продолжайте читать.

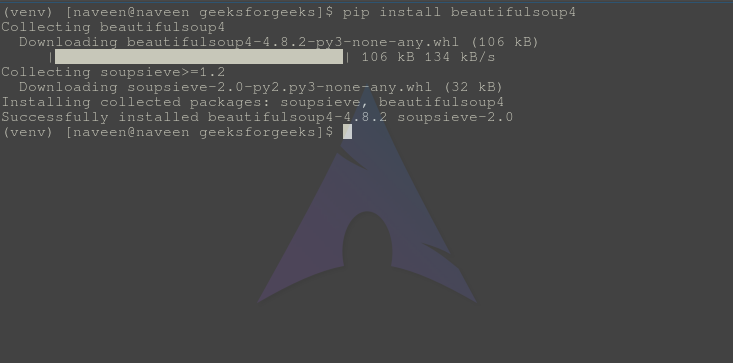

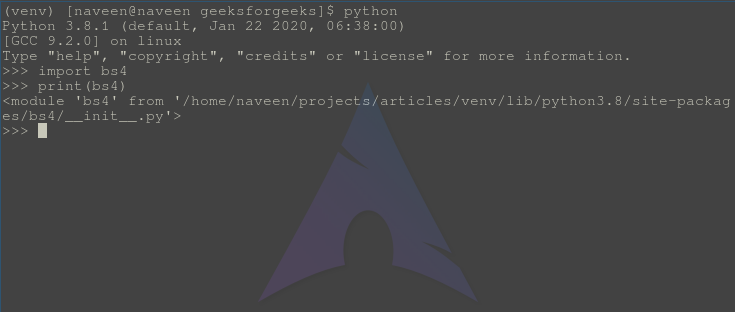

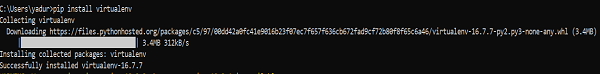

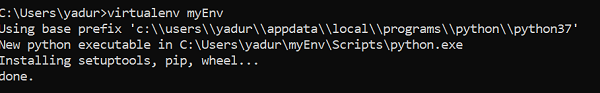

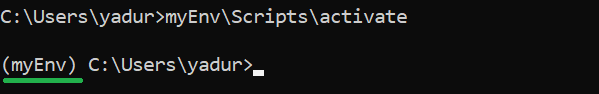

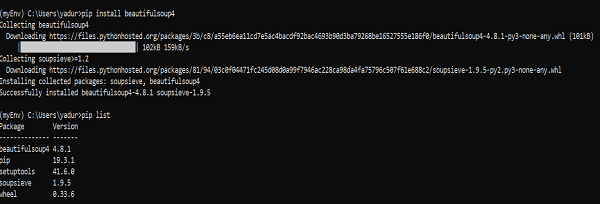

Установка Beautiful Soup¶

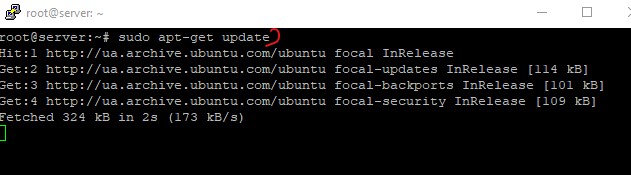

Если вы используете последнюю версию Debian или Ubuntu Linux, вы можете

установить Beautiful Soup с помощью системы управления пакетами:

$ apt-get install python-bs4 (для Python 2)

$ apt-get install python3-bs4 (для Python 3)

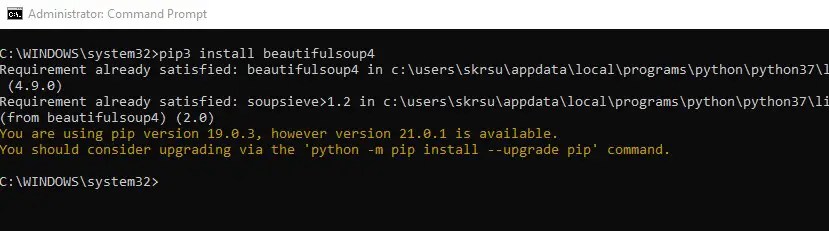

Beautiful Soup 4 публикуется через PyPi, поэтому, если вы не можете установить библиотеку

с помощью системы управления пакетами, можно установить с помощью easy_install или

pip. Пакет называется beautifulsoup4. Один и тот же пакет

работает как на Python 2, так и на Python 3. Убедитесь, что вы используете версию

pip или easy_install, предназначенную для вашей версии Python (их можно назвать

pip3 и easy_install3 соответственно, если вы используете Python 3).

$ easy_install beautifulsoup4

$ pip install beautifulsoup4

(BeautifulSoup — это, скорее всего, не тот пакет, который вам нужен. Это

предыдущий основной релиз, Beautiful Soup 3. Многие программы используют

BS3, так что он все еще доступен, но если вы пишете новый код,

нужно установить beautifulsoup4.)

Если у вас не установлены easy_install или pip, вы можете

скачать архив с исходным кодом Beautiful Soup 4 и

установить его с помощью setup.py.

$ python setup.py install

Если ничего не помогает, лицензия на Beautiful Soup позволяет

упаковать библиотеку целиком вместе с вашим приложением. Вы можете скачать

tar-архив, скопировать из него в кодовую базу вашего приложения каталог bs4

и использовать Beautiful Soup, не устанавливая его вообще.

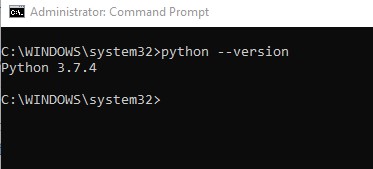

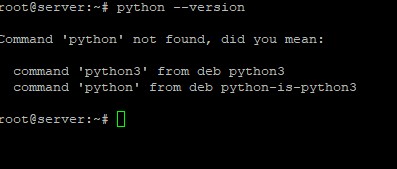

Я использую Python 2.7 и Python 3.2 для разработки Beautiful Soup, но библиотека

должна работать и с более поздними версиями Python.

Проблемы после установки¶

Beautiful Soup упакован как код Python 2. Когда вы устанавливаете его для

использования с Python 3, он автоматически конвертируется в код Python 3. Если

вы не устанавливаете библиотеку в виде пакета, код не будет сконвертирован. Были

также сообщения об установке неправильной версии на компьютерах с

Windows.

Если выводится сообщение ImportError “No module named HTMLParser”, ваша

проблема в том, что вы используете версию кода на Python 2, работая на

Python 3.

Если выводится сообщение ImportError “No module named html.parser”, ваша

проблема в том, что вы используете версию кода на Python 3, работая на

Python 2.

В обоих случаях лучше всего полностью удалить Beautiful

Soup с вашей системы (включая любой каталог, созданный

при распаковке tar-архива) и запустить установку еще раз.

Если выводится сообщение SyntaxError “Invalid syntax” в строке

ROOT_TAG_NAME = u'[document]', вам нужно конвертировать код из Python 2

в Python 3. Вы можете установить пакет:

$ python3 setup.py install

или запустить вручную Python-скрипт 2to3

в каталоге bs4:

$ 2to3-3.2 -w bs4

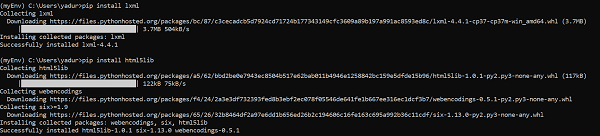

Установка парсера¶

Beautiful Soup поддерживает парсер HTML, включенный в стандартную библиотеку Python,

а также ряд сторонних парсеров на Python.

Одним из них является парсер lxml. В зависимости от ваших настроек,

вы можете установить lxml с помощью одной из следующих команд:

$ apt-get install python-lxml

$ easy_install lxml

$ pip install lxml

Другая альтернатива — написанный исключительно на Python парсер html5lib, который разбирает HTML таким же образом,

как это делает веб-браузер. В зависимости от ваших настроек, вы можете установить html5lib

с помощью одной из этих команд:

$ apt-get install python-html5lib

$ easy_install html5lib

$ pip install html5lib

Эта таблица суммирует преимущества и недостатки каждого парсера:

| Парсер | Типичное использование | Преимущества | Недостатки |

| html.parser от Python | BeautifulSoup(markup, "html.parser") |

|

|

| HTML-парсер в lxml | BeautifulSoup(markup, "lxml") |

|

|

| XML-парсер в lxml | BeautifulSoup(markup, "lxml-xml")BeautifulSoup(markup, "xml") |

|

|

| html5lib | BeautifulSoup(markup, "html5lib") |

|

|

Я рекомендую по возможности установить и использовать lxml для быстродействия. Если вы

используете версию Python 2 более раннюю, чем 2.7.3, или версию Python 3

более раннюю, чем 3.2.2, необходимо установить lxml или

html5lib, потому что встроенный в Python парсер HTML просто недостаточно хорош в старых

версиях.

Обратите внимание, что если документ невалиден, различные парсеры будут генерировать

дерево Beautiful Soup для этого документа по-разному. Ищите подробности в разделе Различия

между парсерами.

Приготовление супа¶

Чтобы разобрать документ, передайте его в

конструктор BeautifulSoup. Вы можете передать строку или открытый дескриптор файла:

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup with open("index.html") as fp: soup = BeautifulSoup(fp) soup = BeautifulSoup("<html>data</html>")

Первым делом документ конвертируется в Unicode, а HTML-мнемоники

конвертируются в символы Unicode:

BeautifulSoup("Sacré bleu!")

<html><head></head><body>Sacré bleu!</body></html>

Затем Beautiful Soup анализирует документ, используя лучший из доступных

парсеров. Библиотека будет использовать HTML-парсер, если вы явно не укажете,

что нужно использовать XML-парсер. (См. Разбор XML.)

Виды объектов¶

Beautiful Soup превращает сложный HTML-документ в сложное дерево

объектов Python. Однако вам придется иметь дело только с четырьмя

видами объектов: Tag, NavigableString, BeautifulSoup

и Comment.

Tag¶

Объект Tag соответствует тегу XML или HTML в исходном документе:

soup = BeautifulSoup('<b class="boldest">Extremely bold</b>') tag = soup.b type(tag) # <class 'bs4.element.Tag'>

У объекта Tag (далее «тег») много атрибутов и методов, и я расскажу о большинстве из них

в разделах Навигация по дереву и Поиск по дереву. На данный момент наиболее

важными особенностями тега являются его имя и атрибуты.

Имя¶

У каждого тега есть имя, доступное как .name:

Если вы измените имя тега, это изменение будет отражено в любой HTML-

разметке, созданной Beautiful Soup:

tag.name = "blockquote" tag # <blockquote class="boldest">Extremely bold</blockquote>

Атрибуты¶

У тега может быть любое количество атрибутов. Тег <b имеет атрибут “id”, значение которого равно

id = "boldest">

“boldest”. Вы можете получить доступ к атрибутам тега, обращаясь с тегом как

со словарем:

Вы можете получить доступ к этому словарю напрямую как к .attrs:

tag.attrs # {u'id': 'boldest'}

Вы можете добавлять, удалять и изменять атрибуты тега. Опять же, это

делается путем обращения с тегом как со словарем:

tag['id'] = 'verybold' tag['another-attribute'] = 1 tag # <b another-attribute="1" id="verybold"></b> del tag['id'] del tag['another-attribute'] tag # <b></b> tag['id'] # KeyError: 'id' print(tag.get('id')) # None

Многозначные атрибуты¶

В HTML 4 определено несколько атрибутов, которые могут иметь множество значений. В HTML 5

пара таких атрибутов удалена, но определено еще несколько. Самый распространённый из

многозначных атрибутов — это class (т. е. тег может иметь более

одного класса CSS). Среди прочих rel, rev, accept-charset,

headers и accesskey. Beautiful Soup представляет значение(я)

многозначного атрибута в виде списка:

css_soup = BeautifulSoup('<p class="body"></p>') css_soup.p['class'] # ["body"] css_soup = BeautifulSoup('<p class="body strikeout"></p>') css_soup.p['class'] # ["body", "strikeout"]

Если атрибут выглядит так, будто он имеет более одного значения, но это не

многозначный атрибут, определенный какой-либо версией HTML-

стандарта, Beautiful Soup оставит атрибут как есть:

id_soup = BeautifulSoup('<p id="my id"></p>') id_soup.p['id'] # 'my id'

Когда вы преобразовываете тег обратно в строку, несколько значений атрибута

объединяются:

rel_soup = BeautifulSoup('<p>Back to the <a rel="index">homepage</a></p>') rel_soup.a['rel'] # ['index'] rel_soup.a['rel'] = ['index', 'contents'] print(rel_soup.p) # <p>Back to the <a rel="index contents">homepage</a></p>

Вы можете отключить объединение, передав multi_valued_attributes = None в качестве

именованного аргумента в конструктор BeautifulSoup:

no_list_soup = BeautifulSoup('<p class="body strikeout"></p>', 'html', multi_valued_attributes=None) no_list_soup.p['class'] # u'body strikeout'

Вы можете использовать get_attribute_list, того чтобы получить значение в виде списка,

независимо от того, является ли атрибут многозначным или нет:

id_soup.p.get_attribute_list('id') # ["my id"]

Если вы разбираете документ как XML, многозначных атрибутов не будет:

xml_soup = BeautifulSoup('<p class="body strikeout"></p>', 'xml') xml_soup.p['class'] # u'body strikeout'

Опять же, вы можете поменять настройку, используя аргумент multi_valued_attributes:

class_is_multi= { '*' : 'class'} xml_soup = BeautifulSoup('<p class="body strikeout"></p>', 'xml', multi_valued_attributes=class_is_multi) xml_soup.p['class'] # [u'body', u'strikeout']

Вряд ли вам это пригодится, но если все-таки будет нужно, руководствуйтесь значениями

по умолчанию. Они реализуют правила, описанные в спецификации HTML:

from bs4.builder import builder_registry builder_registry.lookup('html').DEFAULT_CDATA_LIST_ATTRIBUTES

NavigableString¶

Строка соответствует фрагменту текста в теге. Beautiful Soup

использует класс NavigableString для хранения этих фрагментов текста:

tag.string # u'Extremely bold' type(tag.string) # <class 'bs4.element.NavigableString'>

NavigableString похожа на строку Unicode в Python, не считая того,

что она также поддерживает некоторые функции, описанные в

разделах Навигация по дереву и Поиск по дереву. Вы можете конвертировать

NavigableString в строку Unicode с помощью unicode():

unicode_string = unicode(tag.string) unicode_string # u'Extremely bold' type(unicode_string) # <type 'unicode'>

Вы не можете редактировать строку непосредственно, но вы можете заменить одну строку

другой, используя replace_with():

tag.string.replace_with("No longer bold") tag # <blockquote>No longer bold</blockquote>

NavigableString поддерживает большинство функций, описанных в

разделах Навигация по дереву и Поиск по дереву, но

не все. В частности, поскольку строка не может ничего содержать (в том смысле,

в котором тег может содержать строку или другой тег), строки не поддерживают

атрибуты .contents и .string или метод find().

Если вы хотите использовать NavigableString вне Beautiful Soup,

вам нужно вызвать метод unicode(), чтобы превратить ее в обычную для Python

строку Unicode. Если вы этого не сделаете, ваша строка будет тащить за собой

ссылку на все дерево разбора Beautiful Soup, даже когда вы

закончите использовать Beautiful Soup. Это большой расход памяти.

BeautifulSoup¶

Объект BeautifulSoup представляет разобранный документ как единое

целое. В большинстве случаев вы можете рассматривать его как объект

Tag. Это означает, что он поддерживает большинство методов, описанных

в разделах Навигация по дереву и Поиск по дереву.

Вы также можете передать объект BeautifulSoup в один из методов,

перечисленных в разделе Изменение дерева, по аналогии с передачей объекта Tag. Это

позволяет вам делать такие вещи, как объединение двух разобранных документов:

doc = BeautifulSoup("<document><content/>INSERT FOOTER HERE</document", "xml") footer = BeautifulSoup("<footer>Here's the footer</footer>", "xml") doc.find(text="INSERT FOOTER HERE").replace_with(footer) # u'INSERT FOOTER HERE' print(doc) # <?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> # <document><content/><footer>Here's the footer</footer></document>

Поскольку объект BeautifulSoup не соответствует действительному

HTML- или XML-тегу, у него нет имени и атрибутов. Однако иногда

бывает полезно взглянуть на .name объекта BeautifulSoup, поэтому ему было присвоено специальное «имя»

.name “[document]”:

soup.name # u'[document]'

Комментарии и другие специфичные строки¶

Tag, NavigableString и BeautifulSoup охватывают почти

все, с чем вы столкнётесь в файле HTML или XML, но осталось

ещё немного. Пожалуй, единственное, о чем стоит волноваться,

это комментарий:

markup = "<b><!--Hey, buddy. Want to buy a used parser?--></b>" soup = BeautifulSoup(markup) comment = soup.b.string type(comment) # <class 'bs4.element.Comment'>

Объект Comment — это просто особый тип NavigableString:

comment # u'Hey, buddy. Want to buy a used parser'

Но когда он появляется как часть HTML-документа, Comment

отображается со специальным форматированием:

print(soup.b.prettify()) # <b> # <!--Hey, buddy. Want to buy a used parser?--> # </b>

Beautiful Soup определяет классы для всего, что может появиться в

XML-документе: CData, ProcessingInstruction,

Declaration и Doctype. Как и Comment, эти классы

являются подклассами NavigableString, которые добавляют что-то еще к

строке. Вот пример, который заменяет комментарий блоком

CDATA:

from bs4 import CData cdata = CData("A CDATA block") comment.replace_with(cdata) print(soup.b.prettify()) # <b> # <![CDATA[A CDATA block]]> # </b>

Навигация по дереву¶

Вернемся к HTML-документу с фрагментом из «Алисы в стране чудес»:

html_doc = """ <html><head><title>The Dormouse's story</title></head> <body> <p class="title"><b>The Dormouse's story</b></p> <p class="story">Once upon a time there were three little sisters; and their names were <a href="http://example.com/elsie" class="sister" id="link1">Elsie</a>, <a href="http://example.com/lacie" class="sister" id="link2">Lacie</a> and <a href="http://example.com/tillie" class="sister" id="link3">Tillie</a>; and they lived at the bottom of a well.</p> <p class="story">...</p> """ from bs4 import BeautifulSoup soup = BeautifulSoup (html_doc, 'html.parser')

Я буду использовать его в качестве примера, чтобы показать, как перейти от одной части

документа к другой.

Проход сверху вниз¶

Теги могут содержать строки и другие теги. Эти элементы являются

дочерними (children) для тега. Beautiful Soup предоставляет множество различных атрибутов для

навигации и перебора дочерних элементов.

Обратите внимание, что строки Beautiful Soup не поддерживают ни один из этих

атрибутов, потому что строка не может иметь дочерних элементов.

Навигация с использованием имен тегов¶

Самый простой способ навигации по дереву разбора — это указать имя

тега, который вам нужен. Если вы хотите получить тег <head>, просто напишите soup.head:

soup.head # <head><title>The Dormouse's story</title></head> soup.title # <title>The Dormouse's story</title>

Вы можете повторять этот трюк многократно, чтобы подробнее рассмотреть определенную часть

дерева разбора. Следующий код извлекает первый тег <b> внутри тега <body>:

soup.body.b # <b>The Dormouse's story</b>

Использование имени тега в качестве атрибута даст вам только первый тег с таким

именем:

soup.a # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>

Если вам нужно получить все теги <a> или что-нибудь более сложное,

чем первый тег с определенным именем, вам нужно использовать один из

методов, описанных в разделе Поиск по дереву, такой как find_all():

soup.find_all('a') # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>]

.contents и .children¶

Дочерние элементы доступны в списке под названием .contents:

head_tag = soup.head head_tag # <head><title>The Dormouse's story</title></head> head_tag.contents [<title>The Dormouse's story</title>] title_tag = head_tag.contents[0] title_tag # <title>The Dormouse's story</title> title_tag.contents # [u'The Dormouse's story']

Сам объект BeautifulSoup имеет дочерние элементы. В этом случае

тег <html> является дочерним для объекта BeautifulSoup:

len(soup.contents) # 1 soup.contents[0].name # u'html'

У строки нет .contents, потому что она не может содержать

ничего:

text = title_tag.contents[0] text.contents # AttributeError: У объекта 'NavigableString' нет атрибута 'contents'

Вместо того, чтобы получать дочерние элементы в виде списка, вы можете перебирать их

с помощью генератора .children:

for child in title_tag.children: print(child) # The Dormouse's story

.descendants¶

Атрибуты .contents и .children применяются только в отношении

непосредственных дочерних элементов тега. Например, тег <head> имеет только один непосредственный

дочерний тег <title>:

head_tag.contents # [<title>The Dormouse's story</title>]

Но у самого тега <title> есть дочерний элемент: строка “The Dormouse’s

story”. В некотором смысле эта строка также является дочерним элементом

тега <head>. Атрибут .descendants позволяет перебирать все

дочерние элементы тега рекурсивно: его непосредственные дочерние элементы, дочерние элементы

дочерних элементов и так далее:

for child in head_tag.descendants: print(child) # <title>The Dormouse's story</title> # The Dormouse's story

У тега <head> есть только один дочерний элемент, но при этом у него два потомка:

тег <title> и его дочерний элемент. У объекта BeautifulSoup

только один прямой дочерний элемент (тег <html>), зато множество

потомков:

len(list(soup.children)) # 1 len(list(soup.descendants)) # 25

.string¶

Если у тега есть только один дочерний элемент, и это NavigableString,

его можно получить через .string:

title_tag.string # u'The Dormouse's story'

Если единственным дочерним элементом тега является другой тег, и у этого другого тега есть строка

.string, то считается, что родительский тег содержит ту же строку

.string, что и дочерний тег:

head_tag.contents # [<title>The Dormouse's story</title>] head_tag.string # u'The Dormouse's story'

Если тег содержит больше чем один элемент, то становится неясным, какая из строк

.string относится и к родительскому тегу, поэтому .string родительского тега имеет значение

None:

print(soup.html.string) # None

.strings и .stripped_strings¶

Если внутри тега есть более одного элемента, вы все равно можете посмотреть только на

строки. Используйте генератор .strings:

for string in soup.strings: print(repr(string)) # u"The Dormouse's story" # u'nn' # u"The Dormouse's story" # u'nn' # u'Once upon a time there were three little sisters; and their names weren' # u'Elsie' # u',n' # u'Lacie' # u' andn' # u'Tillie' # u';nand they lived at the bottom of a well.' # u'nn' # u'...' # u'n'

В этих строках много лишних пробелов, которые вы можете

удалить, используя генератор .stripped_strings:

for string in soup.stripped_strings: print(repr(string)) # u"The Dormouse's story" # u"The Dormouse's story" # u'Once upon a time there were three little sisters; and their names were' # u'Elsie' # u',' # u'Lacie' # u'and' # u'Tillie' # u';nand they lived at the bottom of a well.' # u'...'

Здесь строки, состоящие исключительно из пробелов, игнорируются, а

пробелы в начале и конце строк удаляются.

Проход снизу вверх¶

В продолжение аналогии с «семейным деревом», каждый тег и каждая строка имеет

родителя (parent): тег, который его содержит.

.parent¶

Вы можете получить доступ к родительскому элементу с помощью атрибута .parent. В

примере документа с фрагментом из «Алисы в стране чудес» тег <head> является родительским

для тега <title>:

title_tag = soup.title title_tag # <title>The Dormouse's story</title> title_tag.parent # <head><title>The Dormouse's story</title></head>

Строка заголовка сама имеет родителя: тег <title>, содержащий

ее:

title_tag.string.parent # <title>The Dormouse's story</title>

Родительским элементом тега верхнего уровня, такого как <html>, является сам объект

BeautifulSoup:

html_tag = soup.html type(html_tag.parent) # <class 'bs4.BeautifulSoup'>

И .parent объекта BeautifulSoup определяется как None:

print(soup.parent) # None

.parents¶

Вы можете перебрать всех родителей элемента с помощью

.parents. В следующем примере .parents используется для перемещения от тега <a>,

закопанного глубоко внутри документа, до самого верха документа:

link = soup.a link # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a> for parent in link.parents: if parent is None: print(parent) else: print(parent.name) # p # body # html # [document] # None

Перемещение вбок¶

Рассмотрим простой документ:

sibling_soup = BeautifulSoup("<a><b>text1</b><c>text2</c></b></a>") print(sibling_soup.prettify()) # <html> # <body> # <a> # <b> # text1 # </b> # <c> # text2 # </c> # </a> # </body> # </html>

Тег <b> и тег <c> находятся на одном уровне: они оба непосредственные

дочерние элементы одного и того же тега. Мы называем их одноуровневые. Когда документ

красиво отформатирован, одноуровневые элементы выводятся с одинаковым отступом. Вы

также можете использовать это отношение в написанном вами коде.

.next_sibling и .previous_sibling¶

Вы можете использовать .next_sibling и .previous_sibling для навигации

между элементами страницы, которые находятся на одном уровне дерева разбора:

sibling_soup.b.next_sibling # <c>text2</c> sibling_soup.c.previous_sibling # <b>text1</b>

У тега <b> есть .next_sibling, но нет .previous_sibling,

потому что нет ничего до тега <b> на том же уровне

дерева. По той же причине у тега <c> есть .previous_sibling,

но нет .next_sibling:

print(sibling_soup.b.previous_sibling) # None print(sibling_soup.c.next_sibling) # None

Строки “text1” и “text2” не являются одноуровневыми, потому что они не

имеют общего родителя:

sibling_soup.b.string # u'text1' print(sibling_soup.b.string.next_sibling) # None

В реальных документах .next_sibling или .previous_sibling

тега обычно будет строкой, содержащей пробелы. Возвращаясь к

фрагменту из «Алисы в стране чудес»:

<a href="http://example.com/elsie" class="sister" id="link1">Elsie</a> <a href="http://example.com/lacie" class="sister" id="link2">Lacie</a> <a href="http://example.com/tillie" class="sister" id="link3">Tillie</a>

Вы можете подумать, что .next_sibling первого тега <a>

должен быть второй тег <a>. Но на самом деле это строка: запятая и

перевод строки, отделяющий первый тег <a> от второго:

link = soup.a link # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a> link.next_sibling # u',n'

Второй тег <a> на самом деле является .next_sibling запятой

link.next_sibling.next_sibling # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>

.next_siblings и .previous_siblings¶

Вы можете перебрать одноуровневые элементы данного тега с помощью .next_siblings или

.previous_siblings:

for sibling in soup.a.next_siblings: print(repr(sibling)) # u',n' # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a> # u' andn' # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a> # u'; and they lived at the bottom of a well.' # None for sibling in soup.find(id="link3").previous_siblings: print(repr(sibling)) # ' andn' # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a> # u',n' # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a> # u'Once upon a time there were three little sisters; and their names weren' # None

Проход вперед и назад¶

Взгляните на начало фрагмента из «Алисы в стране чудес»:

<html><head><title>The Dormouse's story</title></head> <p class="title"><b>The Dormouse's story</b></p>

HTML-парсер берет эту строку символов и превращает ее в

серию событий: “открыть тег <html>”, “открыть тег <head>”, “открыть

тег <html>”, “добавить строку”, “закрыть тег <title>”, “открыть

тег <p>” и так далее. Beautiful Soup предлагает инструменты для реконструирование

первоначального разбора документа.

.next_element и .previous_element¶

Атрибут .next_element строки или тега указывает на то,

что было разобрано непосредственно после него. Это могло бы быть тем же, что и

.next_sibling, но обычно результат резко отличается.

Возьмем последний тег <a> в фрагменте из «Алисы в стране чудес». Его

.next_sibling является строкой: конец предложения, которое было

прервано началом тега <a>:

last_a_tag = soup.find("a", id="link3") last_a_tag # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a> last_a_tag.next_sibling # '; and they lived at the bottom of a well.'

Но .next_element этого тега <a> — это то, что было разобрано

сразу после тега <a>, не остальная часть этого предложения:

это слово “Tillie”:

last_a_tag.next_element # u'Tillie'

Это потому, что в оригинальной разметке слово «Tillie» появилось

перед точкой с запятой. Парсер обнаружил тег <a>, затем

слово «Tillie», затем закрывающий тег </a>, затем точку с запятой и оставшуюся

часть предложения. Точка с запятой находится на том же уровне, что и тег <a>, но

слово «Tillie» встретилось первым.

Атрибут .previous_element является полной противоположностью

.next_element. Он указывает на элемент, который был встречен при разборе

непосредственно перед текущим:

last_a_tag.previous_element # u' andn' last_a_tag.previous_element.next_element # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>

.next_elements и .previous_elements¶

Вы уже должны были уловить идею. Вы можете использовать их для перемещения

вперед или назад по документу, в том порядке, в каком он был разобран парсером:

for element in last_a_tag.next_elements: print(repr(element)) # u'Tillie' # u';nand they lived at the bottom of a well.' # u'nn' # <p class="story">...</p> # u'...' # u'n' # None

Поиск по дереву¶

Beautiful Soup определяет множество методов поиска по дереву разбора,

но они все очень похожи. Я буду долго объяснять, как работают

два самых популярных метода: find() и find_all(). Прочие

методы принимают практически те же самые аргументы, поэтому я расскажу

о них вкратце.

И опять, я буду использовать фрагмент из «Алисы в стране чудес» в качестве примера:

html_doc = """ <html><head><title>The Dormouse's story</title></head> <body> <p class="title"><b>The Dormouse's story</b></p> <p class="story">Once upon a time there were three little sisters; and their names were <a href="http://example.com/elsie" class="sister" id="link1">Elsie</a>, <a href="http://example.com/lacie" class="sister" id="link2">Lacie</a> and <a href="http://example.com/tillie" class="sister" id="link3">Tillie</a>; and they lived at the bottom of a well.</p> <p class="story">...</p> """ from bs4 import BeautifulSoup soup = BeautifulSoup (html_doc, 'html.parser')

Передав фильтр в аргумент типа find_all(), вы можете

углубиться в интересующие вас части документа.

Виды фильтров¶

Прежде чем подробно рассказывать о find_all() и подобных методах, я

хочу показать примеры различных фильтров, которые вы можете передать в эти

методы. Эти фильтры появляются снова и снова в

поисковом API. Вы можете использовать их для фильтрации по имени тега,

по его атрибутам, по тексту строки или по некоторой их

комбинации.

Строка¶

Самый простой фильтр — это строка. Передайте строку в метод поиска, и

Beautiful Soup выполнит поиск соответствия этой строке. Следующий

код находит все теги <b> в документе:

soup.find_all('b') # [<b>The Dormouse's story</b>]

Если вы передадите байтовую строку, Beautiful Soup будет считать, что строка

кодируется в UTF-8. Вы можете избежать этого, передав вместо нее строку Unicode.

Регулярное выражение¶

Если вы передадите объект с регулярным выражением, Beautiful Soup отфильтрует результаты

в соответствии с этим регулярным выражением, используя его метод search(). Следующий код

находит все теги, имена которых начинаются с буквы “b”; в нашем

случае это теги <body> и <b>:

import re for tag in soup.find_all(re.compile("^b")): print(tag.name) # body # b

Этот код находит все теги, имена которых содержат букву “t”:

for tag in soup.find_all(re.compile("t")): print(tag.name) # html # title

Список¶

Если вы передадите список, Beautiful Soup разрешит совпадение строк

с любым элементом из этого списка. Следующий код находит все теги <a>

и все теги <b>:

soup.find_all(["a", "b"]) # [<b>The Dormouse's story</b>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>]

True¶

Значение True подходит везде, где возможно.. Следующий код находит все

теги в документе, но не текстовые строки:

for tag in soup.find_all(True): print(tag.name) # html # head # title # body # p # b # p # a # a # a # p

Функция¶

Если ничто из перечисленного вам не подходит, определите функцию, которая

принимает элемент в качестве единственного аргумента. Функция должна вернуть

True, если аргумент подходит, и False, если нет.

Вот функция, которая возвращает True, если в теге определен атрибут “class”,

но не определен атрибут “id”:

def has_class_but_no_id(tag): return tag.has_attr('class') and not tag.has_attr('id')

Передайте эту функцию в find_all(), и вы получите все

теги <p>:

soup.find_all(has_class_but_no_id) # [<p class="title"><b>The Dormouse's story</b></p>, # <p class="story">Once upon a time there were...</p>, # <p class="story">...</p>]

Эта функция выбирает только теги <p>. Она не выбирает теги <a>,

поскольку в них определены и атрибут “class” , и атрибут “id”. Она не выбирает

теги вроде <html> и <title>, потому что в них не определен атрибут

“class”.

Если вы передаете функцию для фильтрации по определенному атрибуту, такому как

href, аргументом, переданным в функцию, будет

значение атрибута, а не весь тег. Вот функция, которая находит все теги a,

у которых атрибут href не соответствует регулярному выражению:

def not_lacie(href): return href and not re.compile("lacie").search(href) soup.find_all(href=not_lacie) # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>]

Функция может быть настолько сложной, насколько вам нужно. Вот

функция, которая возвращает True, если тег окружен строковыми

объектами:

from bs4 import NavigableString def surrounded_by_strings(tag): return (isinstance(tag.next_element, NavigableString) and isinstance(tag.previous_element, NavigableString)) for tag in soup.find_all(surrounded_by_strings): print tag.name # p # a # a # a # p

Теперь мы готовы подробно рассмотреть методы поиска.

find_all()¶

Сигнатура: find_all(name, attrs, recursive, string, limit, **kwargs)

Метод find_all() просматривает потомков тега и

извлекает всех потомков, которые соответствую вашим фильтрам. Я привел несколько

примеров в разделе Виды фильтров, а вот еще несколько:

soup.find_all("title") # [<title>The Dormouse's story</title>] soup.find_all("p", "title") # [<p class="title"><b>The Dormouse's story</b></p>] soup.find_all("a") # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>] soup.find_all(id="link2") # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>] import re soup.find(string=re.compile("sisters")) # u'Once upon a time there were three little sisters; and their names weren'

Кое-что из этого нам уже знакомо, но есть и новое. Что означает

передача значения для string или id? Почему

find_all ("p", "title") находит тег <p> с CSS-классом “title”?

Давайте посмотрим на аргументы find_all().

Аргумент name¶

Передайте значение для аргумента name, и вы скажете Beautiful Soup

рассматривать только теги с определенными именами. Текстовые строки будут игнорироваться, так же как и

теги, имена которых не соответствуют заданным.

Вот простейший пример использования:

soup.find_all("title") # [<title>The Dormouse's story</title>]

В разделе Виды фильтров говорилось, что значением name может быть

строка, регулярное выражение, список, функция или

True.

Именованные аргументы¶

Любой нераспознанный аргумент будет превращен в фильтр

по атрибуту тега. Если вы передаете значение для аргумента с именем id,

Beautiful Soup будет фильтровать по атрибуту “id” каждого тега:

soup.find_all(id='link2') # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>]

Если вы передадите значение для href, Beautiful Soup отфильтрует

по атрибуту “href” каждого тега:

soup.find_all(href=re.compile("elsie")) # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>]

Для фильтрации по атрибуту может использоваться строка, регулярное

выражение, список, функция или значение True.

Следующий код находит все теги, атрибут id которых имеет значение,

независимо от того, что это за значение:

soup.find_all(id=True) # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>]

Вы можете отфильтровать несколько атрибутов одновременно, передав более одного

именованного аргумента:

soup.find_all(href=re.compile("elsie"), id='link1') # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">three</a>]

Некоторые атрибуты, такие как атрибуты data-* в HTML 5, имеют имена, которые

нельзя использовать в качестве имен именованных аргументов:

data_soup = BeautifulSoup('<div data-foo="value">foo!</div>') data_soup.find_all(data-foo="value") # SyntaxError: keyword can't be an expression

Вы можете использовать эти атрибуты в поиске, поместив их в

словарь и передав словарь в find_all() как

аргумент attrs:

data_soup.find_all(attrs={"data-foo": "value"}) # [<div data-foo="value">foo!</div>]

Нельзя использовать именованный аргумент для поиска в HTML по элементу “name”,

потому что Beautiful Soup использует аргумент name для имени

самого тега. Вместо этого вы можете передать элемент “name” вместе с его значением в

составе аргумента attrs:

name_soup = BeautifulSoup('<input name="email"/>') name_soup.find_all(name="email") # [] name_soup.find_all(attrs={"name": "email"}) # [<input name="email"/>]

Поиск по классу CSS¶

Очень удобно искать тег с определенным классом CSS, но

имя атрибута CSS, “class”, является зарезервированным словом в

Python. Использование class в качестве именованного аргумента приведет к синтаксической

ошибке. Начиная с Beautiful Soup 4.1.2, вы можете выполнять поиск по классу CSS, используя

именованный аргумент class_:

soup.find_all("a", class_="sister") # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>]

Как и с любым именованным аргументом, вы можете передать в качестве значения class_ строку, регулярное

выражение, функцию или True:

soup.find_all(class_=re.compile("itl")) # [<p class="title"><b>The Dormouse's story</b></p>] def has_six_characters(css_class): return css_class is not None and len(css_class) == 6 soup.find_all(class_=has_six_characters) # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>]

Помните, что один тег может иметь несколько значений

для атрибута “class”. Когда вы ищете тег, который

соответствует определенному классу CSS, вы ищете соответствие любому из его

классов CSS:

css_soup = BeautifulSoup('<p class="body strikeout"></p>') css_soup.find_all("p", class_="strikeout") # [<p class="body strikeout"></p>] css_soup.find_all("p", class_="body") # [<p class="body strikeout"></p>]

Можно искать точное строковое значение атрибута class:

css_soup.find_all("p", class_="body strikeout") # [<p class="body strikeout"></p>]

Но поиск вариантов строкового значения не сработает:

css_soup.find_all("p", class_="strikeout body") # []

Если вы хотите искать теги, которые соответствуют двум или более классам CSS,

следует использовать селектор CSS:

css_soup.select("p.strikeout.body") # [<p class="body strikeout"></p>]

В старых версиях Beautiful Soup, в которых нет ярлыка class_

можно использовать трюк с аргументом attrs, упомянутый выше. Создайте

словарь, значение которого для “class” является строкой (или регулярным

выражением, или чем угодно еще), которую вы хотите найти:

soup.find_all("a", attrs={"class": "sister"}) # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>]

Аргумент string¶

С помощью string вы можете искать строки вместо тегов. Как и в случае с

name и именованными аргументами, передаваться может строка,

регулярное выражение, список, функция или значения True.

Вот несколько примеров:

soup.find_all(string="Elsie") # [u'Elsie'] soup.find_all(string=["Tillie", "Elsie", "Lacie"]) # [u'Elsie', u'Lacie', u'Tillie'] soup.find_all(string=re.compile("Dormouse")) [u"The Dormouse's story", u"The Dormouse's story"] def is_the_only_string_within_a_tag(s): """Return True if this string is the only child of its parent tag.""" return (s == s.parent.string) soup.find_all(string=is_the_only_string_within_a_tag) # [u"The Dormouse's story", u"The Dormouse's story", u'Elsie', u'Lacie', u'Tillie', u'...']

Хотя значение типа string предназначено для поиска строк, вы можете комбинировать его с

аргументами, которые находят теги: Beautiful Soup найдет все теги, в которых

.string соответствует вашему значению для string. Следующий код находит все теги <a>,

у которых .string равно “Elsie”:

soup.find_all("a", string="Elsie") # [<a href="http://example.com/elsie" class="sister" id="link1">Elsie</a>]

Аргумент string — это новое в Beautiful Soup 4.4.0. В ранних

версиях он назывался text:

soup.find_all("a", text="Elsie") # [<a href="http://example.com/elsie" class="sister" id="link1">Elsie</a>]

Аргумент limit¶

find_all() возвращает все теги и строки, которые соответствуют вашим

фильтрам. Это может занять некоторое время, если документ большой. Если вам не

нужны все результаты, вы можете указать их предельное число — limit. Это

работает так же, как ключевое слово LIMIT в SQL. Оно говорит Beautiful Soup

прекратить собирать результаты после того, как их найдено определенное количество.

В фрагменте из «Алисы в стране чудес» есть три ссылки, но следующий код

находит только первые две:

soup.find_all("a", limit=2) # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>]

Аргумент recursive¶

Если вы вызовете mytag.find_all(), Beautiful Soup проверит всех

потомков mytag: его дочерние элементы, дочерние элементы дочерних элементов, и

так далее. Если вы хотите, чтобы Beautiful Soup рассматривал только непосредственных потомков (дочерние элементы),

вы можете передать recursive = False. Оцените разницу:

soup.html.find_all("title") # [<title>The Dormouse's story</title>] soup.html.find_all("title", recursive=False) # []

Вот эта часть документа:

<html> <head> <title> The Dormouse's story </title> </head> ...

Тег <title> находится под тегом <html>, но не непосредственно

под тегом <html>: на пути встречается тег <head>. Beautiful Soup

находит тег <title>, когда разрешено просматривать всех потомков

тега <html>, но когда recursive=False ограничивает поиск

только непосредстввенно дочерними элементами, Beautiful Soup ничего не находит.

Beautiful Soup предлагает множество методов поиска по дереву (они рассмотрены ниже),

и они в основном принимают те же аргументы, что и find_all(): name,

attrs, string, limit и именованные аргументы. Но

с аргументом recursive все иначе: find_all() и find() —

это единственные методы, которые его поддерживают. От передачи recursive=False в

метод типа find_parents() не очень много пользы.

Вызов тега похож на вызов find_all()¶

Поскольку find_all() является самым популярным методом в Beautiful

Soup API, вы можете использовать сокращенную запись. Если относиться к

объекту BeautifulSoup или объекту Tag так, будто это

функция, то это похоже на вызов find_all()

с этим объектом. Эти две строки кода эквивалентны:

soup.find_all("a") soup("a")

Эти две строки также эквивалентны:

soup.title.find_all(string=True) soup.title(string=True)

find()¶

Сигнатура: find(name, attrs, recursive, string, **kwargs)

Метод find_all() сканирует весь документ в поиске

всех результатов, но иногда вам нужен только один. Если вы знаете,

что в документе есть только один тег <body>, нет смысла сканировать

весь документ в поиске остальных. Вместо того, чтобы передавать limit=1

каждый раз, когда вы вызываете find_all(), используйте

метод find(). Эти две строки кода эквивалентны:

soup.find_all('title', limit=1) # [<title>The Dormouse's story</title>] soup.find('title') # <title>The Dormouse's story</title>

Разница лишь в том, что find_all() возвращает список, содержащий

единственный результат, а find() возвращает только сам результат.

Если find_all() не может ничего найти, он возвращает пустой список. Если

find() не может ничего найти, он возвращает None:

print(soup.find("nosuchtag")) # None

Помните трюк с soup.head.title из раздела

Навигация с использованием имен тегов? Этот трюк работает на основе неоднократного вызова find():

soup.head.title # <title>The Dormouse's story</title> soup.find("head").find("title") # <title>The Dormouse's story</title>

find_parents() и find_parent()¶

Сигнатура: find_parents(name, attrs, string, limit, **kwargs)

Сигнатура: find_parent(name, attrs, string, **kwargs)

Я долго объяснял, как работают find_all() и

find(). Beautiful Soup API определяет десяток других методов для

поиска по дереву, но пусть вас это не пугает. Пять из этих методов

в целом похожи на find_all(), а другие пять в целом

похожи на find(). Единственное различие в том, по каким частям

дерева они ищут.

Сначала давайте рассмотрим find_parents() и

find_parent(). Помните, что find_all() и find() прорабатывают

дерево сверху вниз, просматривая теги и их потомков. find_parents() и find_parent()

делают наоборот: они идут снизу вверх, рассматривая

родительские элементы тега или строки. Давайте испытаем их, начав со строки,

закопанной глубоко в фрагменте из «Алисы в стране чудес»:

a_string = soup.find(string="Lacie") a_string # u'Lacie' a_string.find_parents("a") # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>] a_string.find_parent("p") # <p class="story">Once upon a time there were three little sisters; and their names were # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a> and # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>; # and they lived at the bottom of a well.</p> a_string.find_parents("p", class_="title") # []

Один из трех тегов <a> является прямым родителем искомой строки,

так что наш поиск находит его. Один из трех тегов <p> является

непрямым родителем строки, и наш поиск тоже его

находит. Где-то в документе есть тег <p> с классом CSS “title”,

но он не является родительским для строки, так что мы не можем найти

его с помощью find_parents().

Вы могли заметить связь между find_parent(),

find_parents() и атрибутами .parent и .parents,

упомянутыми ранее. Связь очень сильная. Эти методы поиска

на самом деле используют .parents, чтобы перебрать все родительские элементы и проверить

каждый из них на соответствие заданному фильтру.

find_next_siblings() и find_next_sibling()¶

Сигнатура: find_next_siblings(name, attrs, string, limit, **kwargs)

Сигнатура: find_next_sibling(name, attrs, string, **kwargs)

Эти методы используют .next_siblings для

перебора одноуровневых элементов для данного элемента в дереве. Метод

find_next_siblings() возвращает все подходящие одноуровневые элементы,

а find_next_sibling() возвращает только первый из них:

first_link = soup.a first_link # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a> first_link.find_next_siblings("a") # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>] first_story_paragraph = soup.find("p", "story") first_story_paragraph.find_next_sibling("p") # <p class="story">...</p>

find_previous_siblings() и find_previous_sibling()¶

Сигнатура: find_previous_siblings(name, attrs, string, limit, **kwargs)

Сигнатура: find_previous_sibling(name, attrs, string, **kwargs)

Эти методы используют .previous_siblings для перебора тех одноуровневых элементов,

которые предшествуют данному элементу в дереве разбора. Метод find_previous_siblings()

возвращает все подходящие одноуровневые элементы,, а

а find_next_sibling() только первый из них:

last_link = soup.find("a", id="link3") last_link # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a> last_link.find_previous_siblings("a") # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>] first_story_paragraph = soup.find("p", "story") first_story_paragraph.find_previous_sibling("p") # <p class="title"><b>The Dormouse's story</b></p>

find_all_next() и find_next()¶

Сигнатура: find_all_next(name, attrs, string, limit, **kwargs)

Сигнатура: find_next(name, attrs, string, **kwargs)

Эти методы используют .next_elements для

перебора любых тегов и строк, которые встречаются в документе после

элемента. Метод find_all_next() возвращает все совпадения, а

find_next() только первое:

first_link = soup.a first_link # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a> first_link.find_all_next(string=True) # [u'Elsie', u',n', u'Lacie', u' andn', u'Tillie', # u';nand they lived at the bottom of a well.', u'nn', u'...', u'n'] first_link.find_next("p") # <p class="story">...</p>

В первом примере нашлась строка “Elsie”, хотя она

содержится в теге <a>, с которого мы начали. Во втором примере

нашелся последний тег <p>, хотя он находится

в другой части дерева, чем тег <a>, с которого мы начали. Для этих

методов имеет значение только то, что элемент соответствует фильтру и

появляется в документе позже, чем тот элемент, с которого начали поиск.

find_all_previous() и find_previous()¶

Сигнатура: find_all_previous(name, attrs, string, limit, **kwargs)

Сигнатура: find_previous(name, attrs, string, **kwargs)

Эти методы используют .previous_elements для

перебора любых тегов и строк, которые встречаются в документе до

элемента. Метод find_all_previous() возвращает все совпадения, а

find_previous() только первое:

first_link = soup.a first_link # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a> first_link.find_all_previous("p") # [<p class="story">Once upon a time there were three little sisters; ...</p>, # <p class="title"><b>The Dormouse's story</b></p>] first_link.find_previous("title") # <title>The Dormouse's story</title>

Вызов find_all_previous ("p") нашел первый абзац в

документе (тот, который с class = "title"), но он также находит

второй абзац, а именно тег <p>, содержащий тег <a>, с которого мы

начали. Это не так уж удивительно: мы смотрим на все теги,

которые появляются в документе раньше, чем тот, с которого мы начали. Тег

<p>, содержащий тег <a>, должен был появиться до тега <a>, который

в нем содержится.

Селекторы CSS¶

Начиная с версии 4.7.0, Beautiful Soup поддерживает большинство селекторов CSS4 благодаря

проекту SoupSieve. Если вы установили Beautiful Soup через pip, одновременно должен был установиться SoupSieve,

так что вам больше ничего не нужно делать.

В BeautifulSoup есть метод .select(), который использует SoupSieve, чтобы

запустить селектор CSS и вернуть все

подходящие элементы. Tag имеет похожий метод, который запускает селектор CSS

в отношении содержимого одного тега.

(В более ранних версиях Beautiful Soup тоже есть метод .select(),

но поддерживаются только наиболее часто используемые селекторы CSS.)

В документации SoupSieve перечислены все

селекторы CSS, которые поддерживаются на данный момент, но вот некоторые из основных:

Вы можете найти теги:

soup.select("title") # [<title>The Dormouse's story</title>] soup.select("p:nth-of-type(3)") # [<p class="story">...</p>]

Найти теги под другими тегами:

soup.select("body a") # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>] soup.select("html head title") # [<title>The Dormouse's story</title>]

Найти теги непосредственно под другими тегами:

soup.select("head > title") # [<title>The Dormouse's story</title>] soup.select("p > a") # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>] soup.select("p > a:nth-of-type(2)") # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>] soup.select("p > #link1") # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>] soup.select("body > a") # []

Найти одноуровневые элементы тега:

soup.select("#link1 ~ .sister") # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>] soup.select("#link1 + .sister") # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>]

Найти теги по классу CSS:

soup.select(".sister") # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>] soup.select("[class~=sister]") # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>]

Найти теги по ID:

soup.select("#link1") # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>] soup.select("a#link2") # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>]

Найти теги, которые соответствуют любому селектору из списка:

soup.select("#link1,#link2") # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>]

Проверка на наличие атрибута:

soup.select('a[href]') # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>]

Найти теги по значению атрибута:

soup.select('a[href="http://example.com/elsie"]') # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>] soup.select('a[href^="http://example.com/"]') # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/lacie" id="link2">Lacie</a>, # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>] soup.select('a[href$="tillie"]') # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/tillie" id="link3">Tillie</a>] soup.select('a[href*=".com/el"]') # [<a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>]

Есть также метод select_one(), который находит только

первый тег, соответствующий селектору:

soup.select_one(".sister") # <a class="sister" href="http://example.com/elsie" id="link1">Elsie</a>

Если вы разобрали XML, в котором определены пространства имен, вы можете использовать их в

селекторах CSS:

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup xml = """<tag xmlns:ns1="http://namespace1/" xmlns:ns2="http://namespace2/"> <ns1:child>I'm in namespace 1</ns1:child> <ns2:child>I'm in namespace 2</ns2:child> </tag> """ soup = BeautifulSoup(xml, "xml") soup.select("child") # [<ns1:child>I'm in namespace 1</ns1:child>, <ns2:child>I'm in namespace 2</ns2:child>] soup.select("ns1|child", namespaces=namespaces) # [<ns1:child>I'm in namespace 1</ns1:child>]

При обработке селектора CSS, который использует пространства имен, Beautiful Soup

использует сокращения пространства имен, найденные при разборе

документа. Вы можете заменить сокращения своими собственными, передав словарь

сокращений:

namespaces = dict(first="http://namespace1/", second="http://namespace2/") soup.select("second|child", namespaces=namespaces) # [<ns1:child>I'm in namespace 2</ns1:child>]

Все эти селекторы CSS удобны для тех, кто уже

знаком с синтаксисом селекторов CSS. Вы можете сделать все это с помощью

Beautiful Soup API. И если CSS селекторы — это все, что вам нужно, вам следует

использовать парсер lxml: так будет намного быстрее. Но вы можете

комбинировать селекторы CSS с Beautiful Soup API.

Изменение дерева¶

Основная сила Beautiful Soup в поиске по дереву разбора, но вы

также можете изменить дерево и записать свои изменения в виде нового HTML или

XML-документа.

Изменение имен тегов и атрибутов¶

Я говорил об этом раньше, в разделе Атрибуты, но это стоит повторить. Вы

можете переименовать тег, изменить значения его атрибутов, добавить новые

атрибуты и удалить атрибуты:

soup = BeautifulSoup('<b class="boldest">Extremely bold</b>') tag = soup.b tag.name = "blockquote" tag['class'] = 'verybold' tag['id'] = 1 tag # <blockquote class="verybold" id="1">Extremely bold</blockquote> del tag['class'] del tag['id'] tag # <blockquote>Extremely bold</blockquote>

Изменение .string¶

Если вы замените значение атрибута .string новой строкой, содержимое тега будет

заменено на эту строку:

markup = '<a href="http://example.com/">I linked to <i>example.com</i></a>' soup = BeautifulSoup(markup) tag = soup.a tag.string = "New link text." tag # <a href="http://example.com/">New link text.</a>

Будьте осторожны: если тег содержит другие теги, они и все их

содержимое будет уничтожено.

append()¶

Вы можете добавить содержимое тега с помощью Tag.append(). Это работает

точно так же, как .append() для списка в Python:

soup = BeautifulSoup("<a>Foo</a>") soup.a.append("Bar") soup # <html><head></head><body><a>FooBar</a></body></html> soup.a.contents # [u'Foo', u'Bar']

extend()¶

Начиная с версии Beautiful Soup 4.7.0, Tag также поддерживает метод

.extend(), который работает так же, как вызов .extend() для

списка в Python:

soup = BeautifulSoup("<a>Soup</a>") soup.a.extend(["'s", " ", "on"]) soup # <html><head></head><body><a>Soup's on</a></body></html> soup.a.contents # [u'Soup', u''s', u' ', u'on']

NavigableString() и .new_tag()¶

Если вам нужно добавить строку в документ, нет проблем — вы можете передать

строку Python в append() или вызвать

конструктор NavigableString:

soup = BeautifulSoup("<b></b>") tag = soup.b tag.append("Hello") new_string = NavigableString(" there") tag.append(new_string) tag # <b>Hello there.</b> tag.contents # [u'Hello', u' there']

Если вы хотите создать комментарий или другой подкласс

NavigableString, просто вызовите конструктор:

from bs4 import Comment new_comment = Comment("Nice to see you.") tag.append(new_comment) tag # <b>Hello there<!--Nice to see you.--></b> tag.contents # [u'Hello', u' there', u'Nice to see you.']

(Это новая функция в Beautiful Soup 4.4.0.)

Что делать, если вам нужно создать совершенно новый тег? Наилучшим решением будет

вызвать фабричный метод BeautifulSoup.new_tag():

soup = BeautifulSoup("<b></b>") original_tag = soup.b new_tag = soup.new_tag("a", href="http://www.example.com") original_tag.append(new_tag) original_tag # <b><a href="http://www.example.com"></a></b> new_tag.string = "Link text." original_tag # <b><a href="http://www.example.com">Link text.</a></b>

Нужен только первый аргумент, имя тега.

insert()¶

Tag.insert() похож на Tag.append(), за исключением того, что новый элемент

не обязательно добавляется в конец родительского

.contents. Он добавится в любое место, номер которого

вы укажете. Это работает в точности как .insert() в списке Python:

markup = '<a href="http://example.com/">I linked to <i>example.com</i></a>' soup = BeautifulSoup(markup) tag = soup.a tag.insert(1, "but did not endorse ") tag # <a href="http://example.com/">I linked to but did not endorse <i>example.com</i></a> tag.contents # [u'I linked to ', u'but did not endorse', <i>example.com</i>]

insert_before() и insert_after()¶

Метод insert_before() вставляет теги или строки непосредственно

перед чем-то в дереве разбора:

soup = BeautifulSoup("<b>stop</b>") tag = soup.new_tag("i") tag.string = "Don't" soup.b.string.insert_before(tag) soup.b # <b><i>Don't</i>stop</b>

Метод insert_after() вставляет теги или строки непосредственно

после чего-то в дереве разбора:

div = soup.new_tag('div') div.string = 'ever' soup.b.i.insert_after(" you ", div) soup.b # <b><i>Don't</i> you <div>ever</div> stop</b> soup.b.contents # [<i>Don't</i>, u' you', <div>ever</div>, u'stop']

clear()¶

Tag.clear() удаляет содержимое тега:

markup = '<a href="http://example.com/">I linked to <i>example.com</i></a>' soup = BeautifulSoup(markup) tag = soup.a tag.clear() tag # <a href="http://example.com/"></a>

decompose()¶

Tag.decompose() удаляет тег из дерева, а затем полностью

уничтожает его вместе с его содержимым:

markup = '<a href="http://example.com/">I linked to <i>example.com</i></a>' soup = BeautifulSoup(markup) a_tag = soup.a soup.i.decompose() a_tag # <a href="http://example.com/">I linked to</a>

replace_with()¶

PageElement.extract() удаляет тег или строку из дерева

и заменяет его тегом или строкой по вашему выбору:

markup = '<a href="http://example.com/">I linked to <i>example.com</i></a>' soup = BeautifulSoup(markup) a_tag = soup.a new_tag = soup.new_tag("b") new_tag.string = "example.net" a_tag.i.replace_with(new_tag) a_tag # <a href="http://example.com/">I linked to <b>example.net</b></a>

replace_with() возвращает тег или строку, которые были заменены, так что

вы можете изучить его или добавить его обратно в другую часть дерева.

wrap()¶

PageElement.wrap() обертывает элемент в указанный вами тег. Он

возвращает новую обертку:

soup = BeautifulSoup("<p>I wish I was bold.</p>") soup.p.string.wrap(soup.new_tag("b")) # <b>I wish I was bold.</b> soup.p.wrap(soup.new_tag("div") # <div><p><b>I wish I was bold.</b></p></div>

Это новый метод в Beautiful Soup 4.0.5.

unwrap()¶

Tag.unwrap() — это противоположность wrap(). Он заменяет весь тег на

его содержимое. Этим методом удобно очищать разметку:

markup = '<a href="http://example.com/">I linked to <i>example.com</i></a>' soup = BeautifulSoup(markup) a_tag = soup.a a_tag.i.unwrap() a_tag # <a href="http://example.com/">I linked to example.com</a>

Как и replace_with(), unwrap() возвращает тег,

который был заменен.

smooth()¶

После вызова ряда методов, которые изменяют дерево разбора, у вас может оказаться несколько объектов NavigableString подряд. У Beautiful Soup с этим нет проблем, но поскольку такое не случается со свежеразобранным документом, вам может показаться неожиданным следующее поведение:

soup = BeautifulSoup("<p>A one</p>") soup.p.append(", a two") soup.p.contents # [u'A one', u', a two'] print(soup.p.encode()) # <p>A one, a two</p> print(soup.p.prettify()) # <p> # A one # , a two # </p>

Вы можете вызвать Tag.smooth(), чтобы очистить дерево разбора путем объединения смежных строк:

soup.smooth() soup.p.contents # [u'A one, a two'] print(soup.p.prettify()) # <p> # A one, a two # </p>

smooth() — это новый метод в Beautiful Soup 4.8.0.

Вывод¶

Красивое форматирование¶

Метод prettify() превратит дерево разбора Beautiful Soup в

красиво отформатированную строку Unicode, где каждый

тег и каждая строка выводятся на отдельной строчке:

markup = '<a href="http://example.com/">I linked to <i>example.com</i></a>' soup = BeautifulSoup(markup) soup.prettify() # '<html>n <head>n </head>n <body>n <a href="http://example.com/">n...' print(soup.prettify()) # <html> # <head> # </head> # <body> # <a href="http://example.com/"> # I linked to # <i> # example.com # </i> # </a> # </body> # </html>

Вы можете вызвать prettify() для объекта BeautifulSoup верхнего уровня

или для любого из его объектов Tag:

print(soup.a.prettify()) # <a href="http://example.com/"> # I linked to # <i> # example.com # </i> # </a>

Без красивого форматирования¶

Если вам нужна просто строка, без особого форматирования, вы можете вызвать

unicode() или str() для объекта BeautifulSoup или объекта Tag

внутри:

str(soup) # '<html><head></head><body><a href="http://example.com/">I linked to <i>example.com</i></a></body></html>' unicode(soup.a) # u'<a href="http://example.com/">I linked to <i>example.com</i></a>'

Функция str() возвращает строку, кодированную в UTF-8. Для получения более подробной информации см.

Кодировки.

Вы также можете вызвать encode() для получения байтовой строки, и decode(),

чтобы получить Unicode.

Средства форматирования вывода¶

Если вы дадите Beautiful Soup документ, который содержит HTML-мнемоники, такие как

“&lquot;”, они будут преобразованы в символы Unicode:

soup = BeautifulSoup("“Dammit!” he said.") unicode(soup) # u'<html><head></head><body>u201cDammit!u201d he said.</body></html>'

Если затем преобразовать документ в строку, символы Unicode

будет кодироваться как UTF-8. Вы не получите обратно HTML-мнемоники:

str(soup) # '<html><head></head><body>xe2x80x9cDammit!xe2x80x9d he said.</body></html>'

По умолчанию единственные символы, которые экранируются при выводе — это чистые

амперсанды и угловые скобки. Они превращаются в «&», «<»

и “>”, чтобы Beautiful Soup случайно не сгенерировал

невалидный HTML или XML:

soup = BeautifulSoup("<p>The law firm of Dewey, Cheatem, & Howe</p>") soup.p # <p>The law firm of Dewey, Cheatem, & Howe</p> soup = BeautifulSoup('<a href="http://example.com/?foo=val1&bar=val2">A link</a>') soup.a # <a href="http://example.com/?foo=val1&bar=val2">A link</a>

Вы можете изменить это поведение, указав для

аргумента formatter одно из значений: prettify(), encode() или

decode(). Beautiful Soup распознает пять возможных значений

formatter.

Значение по умолчанию — formatter="minimal". Строки будут обрабатываться

ровно настолько, чтобы Beautiful Soup генерировал валидный HTML / XML:

french = "<p>Il a dit <<Sacré bleu!>></p>" soup = BeautifulSoup(french) print(soup.prettify(formatter="minimal")) # <html> # <body> # <p> # Il a dit <<Sacré bleu!>> # </p> # </body> # </html>

Если вы передадите formatter = "html", Beautiful Soup преобразует

символы Unicode в HTML-мнемоники, когда это возможно:

print(soup.prettify(formatter="html")) # <html> # <body> # <p> # Il a dit <<Sacré bleu!>> # </p> # </body> # </html>

Если вы передаете formatter="html5", это то же самое, что

formatter="html", только Beautiful Soup будет

пропускать закрывающую косую черту в пустых тегах HTML, таких как “br”:

soup = BeautifulSoup("<br>") print(soup.encode(formatter="html")) # <html><body><br/></body></html> print(soup.encode(formatter="html5")) # <html><body><br></body></html>

Если вы передадите formatter=None, Beautiful Soup вообще не будет менять

строки на выходе. Это самый быстрый вариант, но он может привести

к тому, что Beautiful Soup будет генерировать невалидный HTML / XML:

print(soup.prettify(formatter=None)) # <html> # <body> # <p> # Il a dit <<Sacré bleu!>> # </p> # </body> # </html> link_soup = BeautifulSoup('<a href="http://example.com/?foo=val1&bar=val2">A link</a>') print(link_soup.a.encode(formatter=None)) # <a href="http://example.com/?foo=val1&bar=val2">A link</a>

Если вам нужен более сложный контроль над выводом, вы можете

использовать класс Formatter из Beautiful Soup. Вот как можно

преобразовать строки в верхний регистр, независимо от того, находятся ли они в текстовом узле или в

значении атрибута:

from bs4.formatter import HTMLFormatter def uppercase(str): return str.upper() formatter = HTMLFormatter(uppercase) print(soup.prettify(formatter=formatter)) # <html> # <body> # <p> # IL A DIT <<SACRÉ BLEU!>> # </p> # </body> # </html> print(link_soup.a.prettify(formatter=formatter)) # <a href="HTTP://EXAMPLE.COM/?FOO=VAL1&BAR=VAL2"> # A LINK # </a>

Подклассы HTMLFormatter или XMLFormatter дают еще

больший контроль над выводом. Например, Beautiful Soup сортирует

атрибуты в каждом теге по умолчанию:

attr_soup = BeautifulSoup(b'<p z="1" m="2" a="3"></p>') print(attr_soup.p.encode()) # <p a="3" m="2" z="1"></p>

Чтобы выключить сортировку по умолчанию, вы можете создать подкласс на основе метода Formatter.attributes(),

который контролирует, какие атрибуты выводятся и в каком

порядке. Эта реализация также отфильтровывает атрибут с именем “m”,

где бы он ни появился:

class UnsortedAttributes(HTMLFormatter): def attributes(self, tag): for k, v in tag.attrs.items(): if k == 'm': continue yield k, v print(attr_soup.p.encode(formatter=UnsortedAttributes())) # <p z="1" a="3"></p>

Последнее предостережение: если вы создаете объект CData, текст внутри

этого объекта всегда представлен как есть, без какого-либо

форматирования. Beautiful Soup вызовет вашу функцию для замены мнемоник,

на тот случай, если вы написали функцию, которая подсчитывает

все строки в документе или что-то еще, но он будет игнорировать

возвращаемое значение:

from bs4.element import CData soup = BeautifulSoup("<a></a>") soup.a.string = CData("one < three") print(soup.a.prettify(formatter="xml")) # <a> # <![CDATA[one < three]]> # </a>

get_text()¶

Если вам нужна только текстовая часть документа или тега, вы можете использовать

метод get_text(). Он возвращает весь текст документа или

тега в виде единственной строки Unicode:

markup = '<a href="http://example.com/">nI linked to <i>example.com</i>n</a>' soup = BeautifulSoup(markup) soup.get_text() u'nI linked to example.comn' soup.i.get_text() u'example.com'

Вы можете указать строку, которая будет использоваться для объединения текстовых фрагментов

в единую строку:

# soup.get_text("|") u'nI linked to |example.com|n'

Вы можете сказать Beautiful Soup удалять пробелы в начале и

конце каждого текстового фрагмента:

# soup.get_text("|", strip=True) u'I linked to|example.com'

Но в этом случае вы можете предпочесть использовать генератор .stripped_strings

и затем обработать текст самостоятельно:

[text for text in soup.stripped_strings] # [u'I linked to', u'example.com']

Указание парсера¶

Если вам нужно просто разобрать HTML, вы можете скинуть разметку в

конструктор BeautifulSoup, и, скорее всего, все будет в порядке. Beautiful

Soup подберет для вас парсер и проанализирует данные. Но есть

несколько дополнительных аргументов, которые вы можете передать конструктору, чтобы изменить

используемый парсер.

Первым аргументом конструктора BeautifulSou является строка или

открытый дескриптор файла — сама разметка, которую вы хотите разобрать. Второй аргумент — это

как вы хотите, чтобы разметка была разобрана.

Если вы ничего не укажете, будет использован лучший HTML-парсер из тех,

которые установлены. Beautiful Soup оценивает парсер lxml как лучший, за ним идет

html5lib, затем встроенный парсер Python. Вы можете переопределить используемый парсер,

указав что-то из следующего:

- Какой тип разметки вы хотите разобрать. В данный момент поддерживаются:

“html”, “xml” и “html5”. - Имя библиотеки парсера, которую вы хотите использовать. В данный момент поддерживаются

“lxml”, “html5lib” и “html.parser” (встроенный в Python

парсер HTML).

В разделе Установка парсера вы найдете сравнительную таблицу поддерживаемых парсеров.

Если у вас не установлен соответствующий парсер, Beautiful Soup

проигнорирует ваш запрос и выберет другой парсер. На текущий момент единственный

поддерживаемый парсер XML — это lxml. Если у вас не установлен lxml, запрос на

парсер XML ничего не даст, и запрос “lxml” тоже

не сработает.

Различия между парсерами¶

Beautiful Soup представляет один интерфейс для разных

парсеров, но парсеры неодинаковы. Разные парсеры создадут

различные деревья разбора из одного и того же документа. Самые большие различия будут

между парсерами HTML и парсерами XML. Вот короткий

документ, разобранный как HTML:

BeautifulSoup("<a><b /></a>") # <html><head></head><body><a><b></b></a></body></html>

Поскольку пустой тег <b /> не является валидным кодом HTML, парсер превращает его в

пару тегов <b></b>.

Вот тот же документ, который разобран как XML (для его запуска нужно, чтобы был

установлен lxml). Обратите внимание, что пустой тег <b /> остается, и

что в документ добавляется объявление XML вместо

тега <html>:

BeautifulSoup("<a><b /></a>", "xml") # <?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> # <a><b/></a>

Есть также различия между парсерами HTML. Если вы даете Beautiful

Soup идеально оформленный документ HTML, эти различия не будут

иметь значения. Один парсер будет быстрее другого, но все они будут давать

структуру данных, которая выглядит точно так же, как оригинальный

документ HTML.

Но если документ оформлен неидеально, различные парсеры

дадут разные результаты. Вот короткий невалидный документ, разобранный с помощью

HTML-парсера lxml. Обратите внимание, что висячий тег </p> просто

игнорируется:

BeautifulSoup("<a></p>", "lxml") # <html><body><a></a></body></html>

Вот тот же документ, разобранный с помощью html5lib: