Виртуальные среды (окружения) используются в Python 3 контроля версионности пакетов. Кроме контроля версий среды используют для использования разных интерпретаторов. Самих пакетов, которые создают виртуальные окружения много. В этой статье речь пойдет про venv, virtualenv и virtualenvwrapper.

Для чего нужно виртуальные среды?

При создании скрипта или программы вы часто используете сторонние модули (пакеты). Если в последующем потребуется перенос программы на другой компьютер, то вы можете столкнуться с двумя проблемами:

- Нужные пакеты отсутствуют на новом компьютере и придется проверять каждый файл программы для их поиска. Либо получить список установленных пакетов через «pip list» на старом компьютере, который выведет множество лишних модулей.

- Даже если количество пакетов или файлов программ маленькое, или вы его создали отдельно, то вы все равно можете столкнуться с проблемами в версиях. Пакеты могли быть обновлены, а методы и классы изменены.

Использование виртуальных сред избавляет вас от этих проблем. В таком виртуальной среде находится свой интерпретатор, свой pip и все пакеты относятся только к нему. Так же, весь проект, можно перенести как папку на другой компьютер без ошибок.

Кроме этого вы можете запускать разные версии Python в разных виртуальных средах, что сильно упрощает работу.

Установка и создания окружения с virtualenv

Самый популярный пакет, который используется для создания виртуальных сред в Python, это virtualenv. Для его установки на Windows выполните:

pip install virtualenvДля установки на Linux системах, для Python 3, понадобится выполнить такую команду:

sudo pip3 install virtualenvЕсли вы не будете использовать sudo, то в зависимости от версии ОС у вас появятся разные ошибки. В CentOS установка не выполнится вовсе, а в Ubuntu не будет добавлен путь в переменную окружения:

- PermissionError: [Errno 13] Permission denied: ‘/usr/local/lib/python3.6’

- Command ‘virtualenv’ not found, but can be installed with: sudo apt install virtualenv

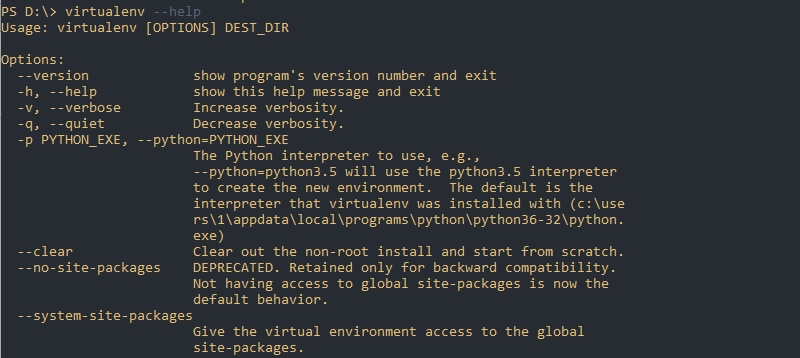

Далее, вне зависимости от того используете ли вы Linux или Windows, вы можете выполнить команду получения справки:

virtualenv --helpЯ использую Python 3.6, и так я создам окружение в папке projectname/venv:

virtualenv -p python3.6 project/venvСпособ выше устанавливает окружение относительно текущего пути. Если нужно установить на другом диске или каталоге, то можно использовать абсолютный путь. Так же не обязательно указывать параметр «-p» если вы используете одну версию Python. Вариант как это может быть сделано на Windows:

virtualenv D:projectvenvСамо расположение виртуального окружения рекомендуется создавать в одной папке вместе разрабатываемым приложением. Такую структуру будет легче сопровождать. Я обычно придерживаюсь такой структуры:

-projectname # Каталог проекта

--venv # Окружение

--app # Каталог с приложениемАктивация и выход из окружения

Для того что бы виртуальное окружения начало работать его нужно активировать. В разных ОС это делается по-разному.

В случаях с Linux указываем полный путь до venv/bin/activate:

source project/venv/bin/activateДля активации в Windows, в папке venvScripts есть несколько файлов:

- activate.ps1 — для активации через Powershell;

- activate.bat — для активации через CMD.

Для активации просто укажите полный путь до файла. Например:

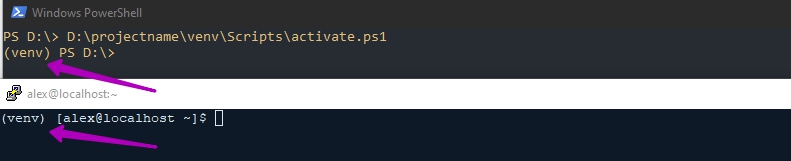

D:projectnamevenvScriptsactivate.ps1О том что вы находитесь в виртуальном окружении свидетельствуют следующие надписи:

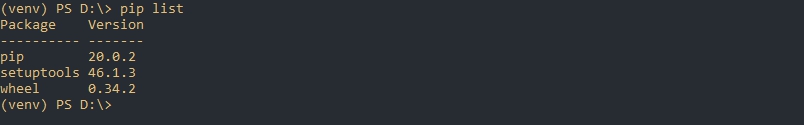

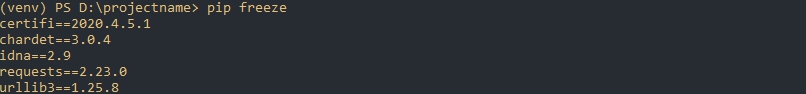

Вы так же можете сравнить количество установленных пакетов внутри виртуального окружения с тем, что установлено вне:

pip listТеперь вы можете устанавливать пакеты, которые будут работать только в этой среде.

Для выхода из окружения, за исключением запуска с помощью CMD, используйте команду:

deactivateДля CMD нужно указать путь до файла «venvScriptsdeactivate.bat».

Управление средами через virtualenvwrapper

Если вы создаете множество виртуальных сред, например для тестирования в разных версиях Python, вы можете использовать virtualenvwrapper. Этот пакет представляет собой надстройку для virtualenv для более удобной работы и устанавливается отдельно.

Благодаря этому пакету мы сможем запускать ваши окружения так:

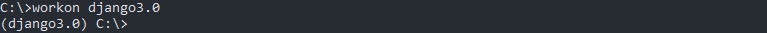

workon project_name

# вместо

source project_name/venv/bin/activateДля Windows нужно установить следующий пакет:

pip install virtualenvwrapper-winДля Linux нужно так же использовать sudo:

sudo pip3 install virtualenvwrapperНастройки для Linux

Virtualenvwrapper хранит все окружения в одном месте. Это место определяется через переменную WORKON_HOME в Linux и по умолчанию равно директории ‘/home/пользователь/.virtualenvs’. Если вы хотите изменить это расположение — выполните команду экспорта с нужным путем:

export WORKON_HOME = /var/envs/

# Создание директории

source ~/.bashrc

mkdir -p $WORKON_HOMEСледующая команда добавит скрипты в домашний каталог для удобной работы:

source /usr/local/bin/virtualenvwrapper.sh

# Если путь отличается, то файл virtualenvwrapper.sh можно найти так

which virtualenvwrapper.shПри выполнении предыдущей команды у меня появилась ошибка:

virtualenvwrapper.sh: There was a problem running the initialization hooks. If Python could not import the module virtualenvwrapper.hook_loader

Она исправилась добавлением переменной в env с путем до нужного интерпретатора:

export VIRTUALENVWRAPPER_PYTHON=/usr/bin/python3Настройки для Windows

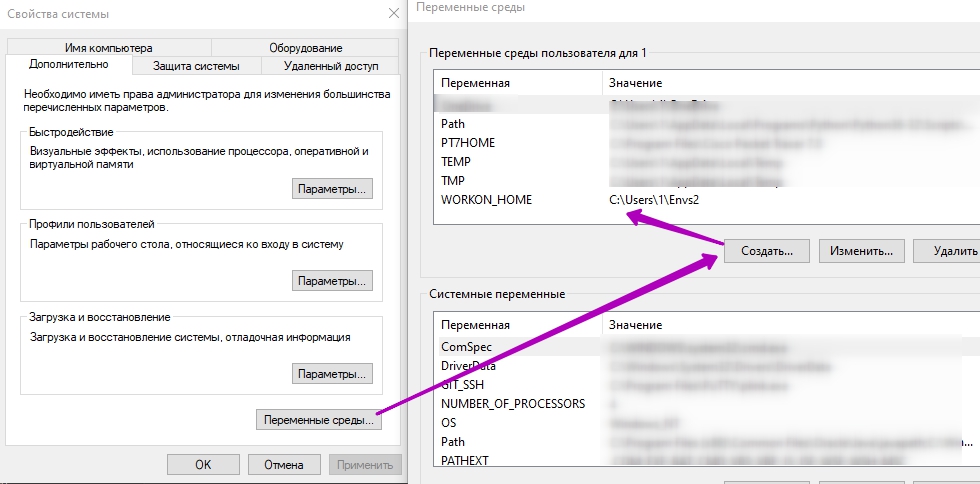

Все виртуальные среды, которые будут созданы, по умолчанию будут располагаться по пути «C:Users%USERNAME%Envs». Если вам нужно изменить расположение, то создайте переменную WORKON_HOME с нужной директорией:

Важный момент, в случае с Windows, команды virtualenvwrapper не будут выполняться Powershell. Команды работают только через CMD.

Основные команды

Далее мы можем использовать следующие команды (основные):

- mkvirtualenv — создание окружения;

- lsvirtualenv — отображение списка окружений;

- rmvirtualenv — удаление;

- workon — переключение между виртуальными средами;

- deactivate — выход из текущего окружения.

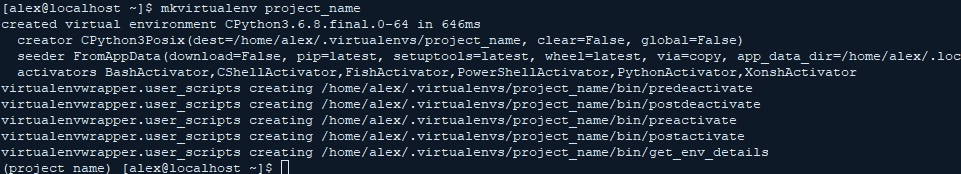

Так мы создадим виртуальную среду:

mkvirtualenv project_nameТак выйдем из созданной среды:

deactivateАктивация окружения:

workon django3.0Если нужно использовать другую версию Python:

mkvirtualenv -p python2.7 project_name/venvПолучение справки:

mkvirtualenv -hСоздание виртуальных сред со встроенным пакетом Python venv

Ранее, до версии Python >= 3.6 базовая установка интерпретатора шла вместе с пакетом pyenv, но на данный момент он считается устаревшим и более не поддерживается. На его смену пришел venv. В некоторых версиях ОС (Ubuntu/Debian) может потребоваться его отдельная установка:

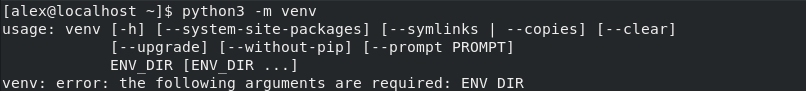

sudo apt install python3-venvПроверить, то что пакет venv установлен, можно так:

python -m venv

# или

python3 -m venvСледующая команда создаст виртуальную среду:

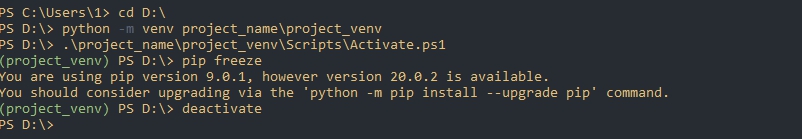

python -m venv C:project_nameproject_venv

# или

python3 -m venv /var/project_name/project_venvВыбранная версия Python и стандартные библиотеки будут скопированы в указанную папку.

Активация окружения выполняется следующим образом:

# CMD

C:project_nameproject_venvScriptsactivate.bat

# Powershell

C:project_nameproject_venvScriptsActivate.ps1

# Bash

project_name/project_venv/bin/activateДля выхода из окружения:

# CMD

C:project_nameproject_venvScriptsdeactivate.bat

# Powershell и bash

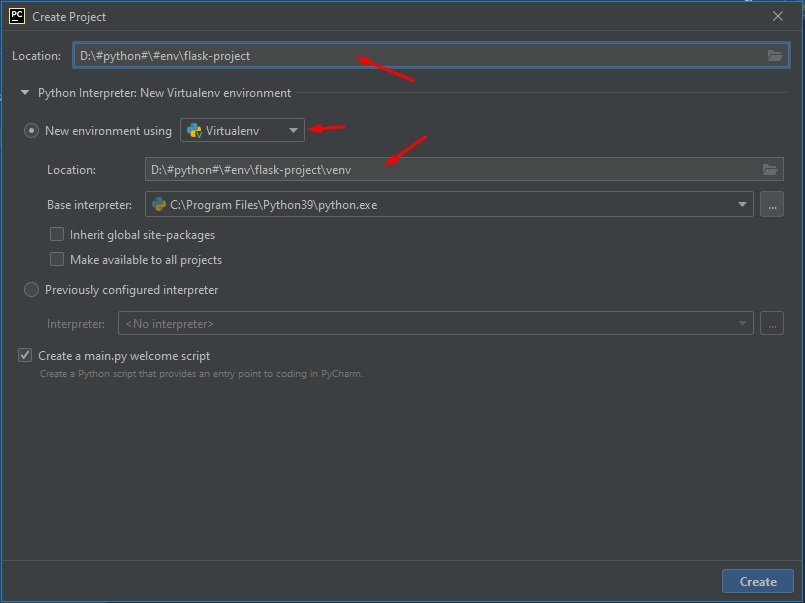

deactivateСоздание виртуального окружения в Pycharm

В некоторых IDE, например Pycharm, консоль встроенная и по умолчанию у вас будет запускаться интерпретатор выбранный в настройках. В Pycharm вы можете создать или изменить проект привязав его к определенному интерпретатору.

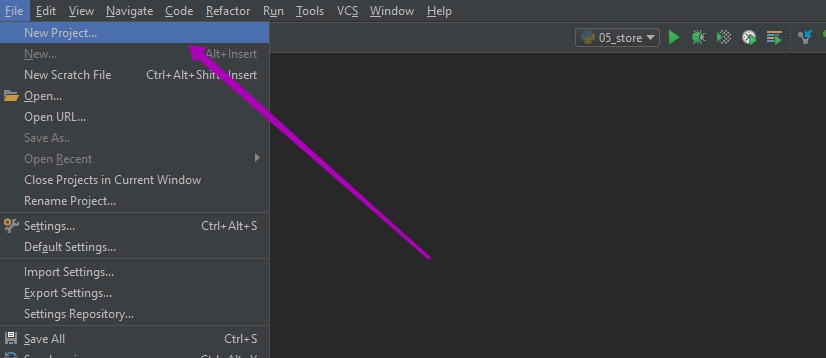

Виртуальную среду можно создать при создании нового проекта. Для этого нужно зайти по следующему пути:

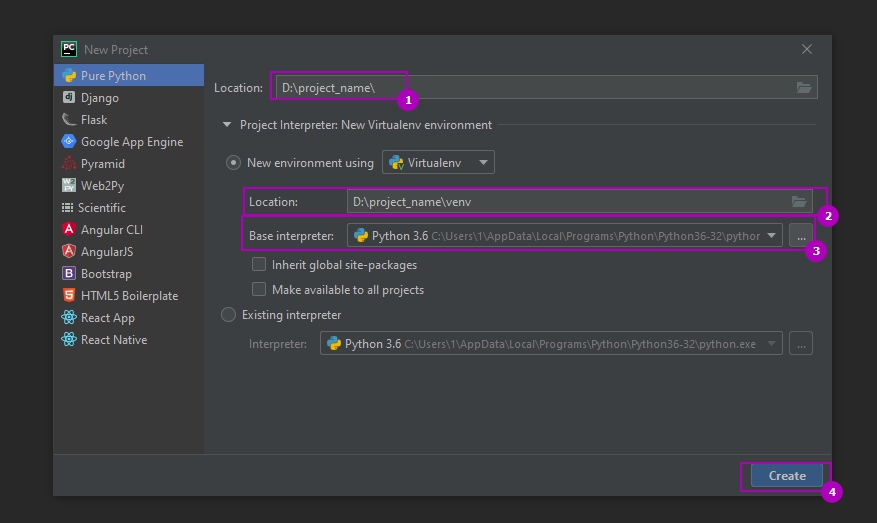

В новом окне выбрать название проекта, место для копирования, интерпретатор и нажать кнопку создания окружения:

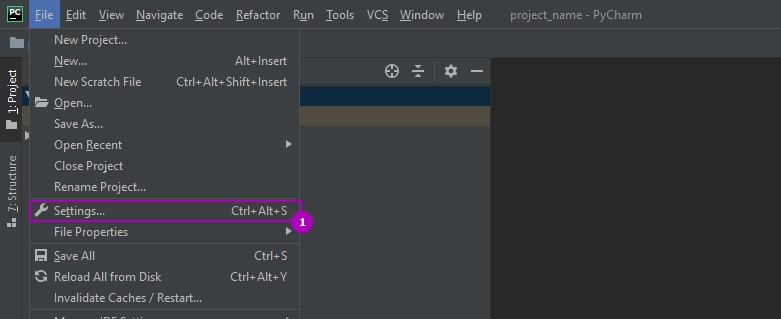

Для настройки окружения для старых проектов нужно зайти в настройки:

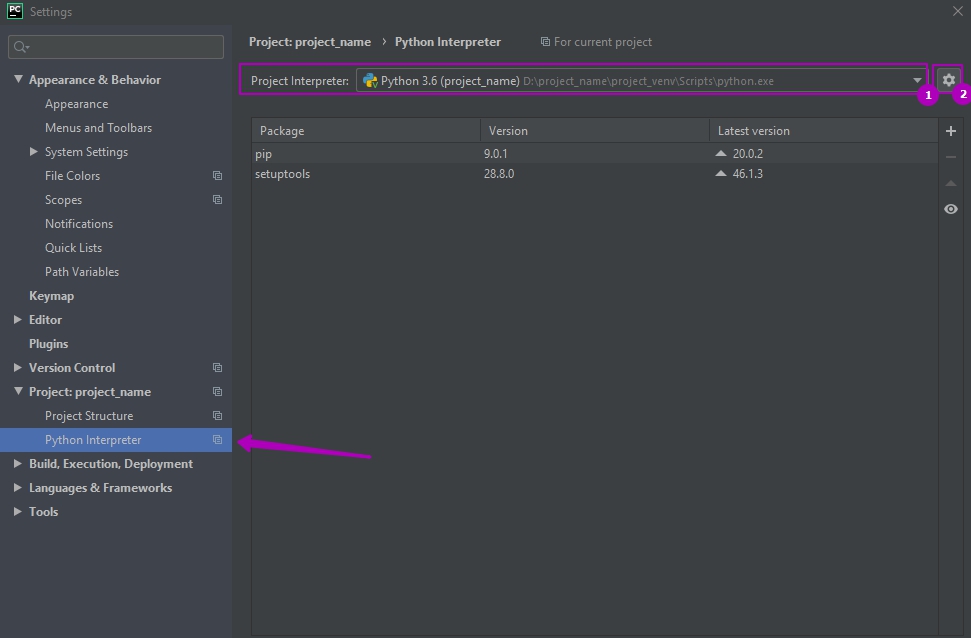

Во вкладе «Python Interpreter» будет выбор из существующих интерпретаторов (1). Либо можно создать новый (2):

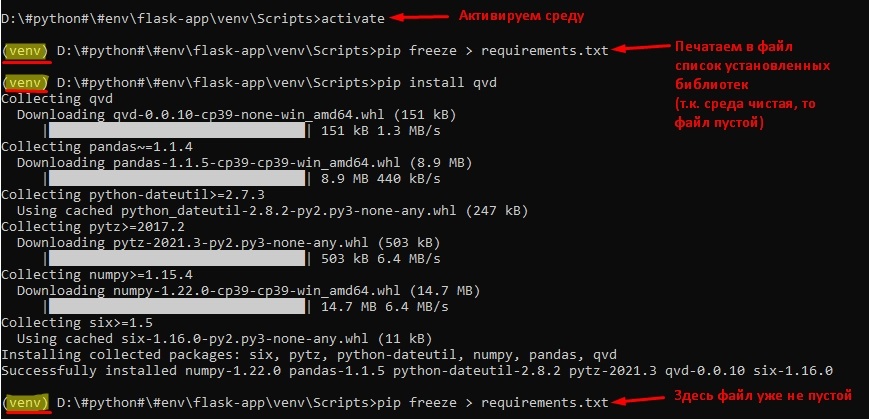

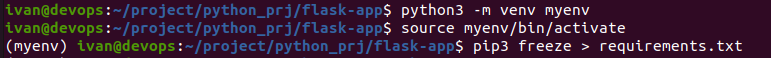

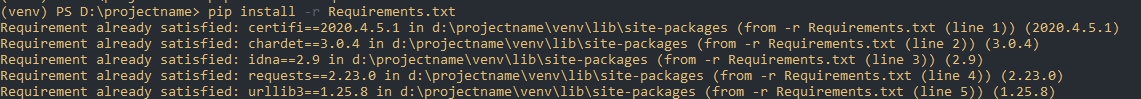

Создание списка установленных пакетов Requirements.txt

Используя виртуальные окружения можно легко создавать файл, в котором будут собраны все названия и версии пакетов для определенного проекта. Этот подход используется для удобства работы, так как одной программой мы сразу установим нужные пакеты.

Так мы получим список пакетов, установленных в виртуальном окружении, в формате читаемом pip:

pip freezeСледующим способом мы экспортируем этот список в файл Requirements.txt (способ подходит для Bash/CMD/Powershell):

pip freeze > Requirements.txtНа другом компьютере/среде мы можем этот список быстро проверить и установить отсутствующие пакеты следующей командой:

pip install -r Requirements.txt

…

Теги:

#python

#virtualenv

#venv

Язык программирования Python считается достаточно простым. На нем легче и быстрее пишутся программы, по сравнению с компилируемыми языками программирования. Для Python существует множество библиотек, позволяющих решать практически любые задачи. Есть, конечно, и минусы и другие нюансы, но это отдельная тема.

Довольно часто я вижу, как мои знакомые и друзья начинают изучать Python и сталкиваются с проблемой установки и использования сторонних библиотек. Они могут несколько часов потратить на установку библиотеки, и даже, могут не справиться с этим и забить на неё. В то время как, в большинстве случаев, это можно было сделать за несколько минут.

Статья начинается с базовых вещей: с установки Python 3, инструментов разработки Pip и Virtualenv и среды разработки PyCharm в Windows и в Ubuntu. Для многих это не представляет трудностей и возможно, что уже всё установлено.

После чего будет то, ради чего задумывалась статья, я покажу как в PyCharm создавать и использовать виртуальные окружения и устанавливать в них библиотеки с помощью Pip.

Установка Python и Pip

Pip является менеджером пакетов для Python. Именно с помощью него обычно устанавливаются модули/библиотеки для разработки в виде пакетов. В Windows Pip можно установить через стандартный установщик Python. В Ubuntu Pip ставится отдельно.

Установка Python и Pip в Windows

Для windows заходим на официальную страницу загрузки, где затем переходим на страницу загрузки определенной версии Python. У меня используется Python 3.6.8, из-за того, что LLVM 9 требует установленного Python 3.6.

Далее в таблице с файлами выбираем «Windows x86-64 executable installer» для 64-битной системы или «Windows x86 executable installer» для 32-битной. И запускаем скачанный установщик, например, для версии Python 3.8.1 он называется python-3.8.1-amd64.exe.

Во время установки ставим галочку возле Add Python 3.x to PATH и нажимаем Install Now:

Установка Python и Pip в Ubuntu

В Ubuntu установить Python 3 можно через терминал. Запускаем его и вводим команду установки. Вторая команда выводит версию Python.

sudo apt install python3-minimal

python3 -VДалее устанавливаем Pip и обновляем его. После обновления необходимо перезапустить текущую сессию (или перезагрузить компьютер), иначе возникнет ошибка во время вызова Pip.

sudo apt install python3-pip

pip3 install --user --upgrade pipОсновные команды Pip

Рассмотрим основные команды при работе с Pip в командой строке Windows и в терминале Ubuntu.

Если виртуальные окружения не используются, то во время установки пакета(ов) полезно использовать дополнительно ключ --user, устанавливая пакет(ы) локально только для текущего пользователя.

Установка VirtualEnv и VirtualEnvWrapper

VirtualEnv используется для создания виртуальных окружений для Python программ. Это необходимо для избежания конфликтов, позволяя установить одну версию библиотеки для одной программы, и другу для второй. Всё удобство использования VirtualEnv постигается на практике.

Установка VirtualEnv и VirtualEnvWrapper в Windows

В командной строке выполняем команды:

pip install virtualenv

pip install virtualenvwrapper-winУстановка VirtualEnv и VirtualEnvWrapper в Ubuntu

Для Ubuntu команда установки будет следующей:

pip3 install --user virtualenv virtualenvwrapperПосле которой в конец ~/.bashrc добавляем:

export VIRTUALENVWRAPPER_PYTHON=/usr/bin/python3

source ~/.local/bin/virtualenvwrapper.shПри новом запуске терминала должны будут появиться сообщения, начинающиеся на virtualenvwrapper.user_scripts creating, что говорит об успешном завершении установки.

Работа с виртуальным окружением VirtualEnv

Рассмотрим основные команды при работе с VirtualEnv в командой строке Windows и в терминале Ubuntu.

Находясь в одном из окружений, можно ставить пакеты через Pip, как обычно и нет необходимости добавлять ключ --user:

pip3 install markdownДля Windows можно указать в переменных среды WORKON_HOME для переопределения пути, где хранятся виртуальные окружения. По умолчанию, используется путь %USERPROFILE%Envs.

Установка PyCharm

PyCharm — интегрированная среда разработки для языка программирования Python. Обладает всеми базовыми вещами необходимых для разработки. В нашем случае огромное значение имеет хорошее взаимодействие PyCharm с VirtualEnv и Pip, чем мы и будем пользоваться.

Установка PyCharm в Windows

Скачиваем установщик PyCharm Community для Windows с официального сайта JetBrains. Если умеете проверять контрольные суммы у скаченных файлов, то не забываем это сделать.

В самой установке ничего особенного нету. По сути только нажимаем на кнопки next, и в завершение на кнопку Install. Единственно, можно убрать версию из имени папки установки, т.к. PyCharm постоянно обновляется и указанная версия в будущем станет не правильной.

Установка PyCharm в Ubuntu

Скачиваем установщик PyCharm Community для Linux с официального сайта JetBrains. Очень хорошей практикой является проверка контрольных сумм, так что если умеете, не ленитесь с проверкой.

Распаковываем архив с PyCharm и переименовываем папку с программой в pycharm-community, убрав версию из названия.

Теперь в директории ~/.local (Ctrl + H — Показ скрытый файлов), создаем папку opt, куда и перемещаем pycharm-community. В результате по пути /.local/opt/pycharm-community должны размещаться папки bin, help и т.д. Таким образом PyCharm будет находится в своём скромном месте и никому не будет мешать.

Далее выполняем команды в терминале:

cd /home/maksim/.local/opt/pycharm-community/bin

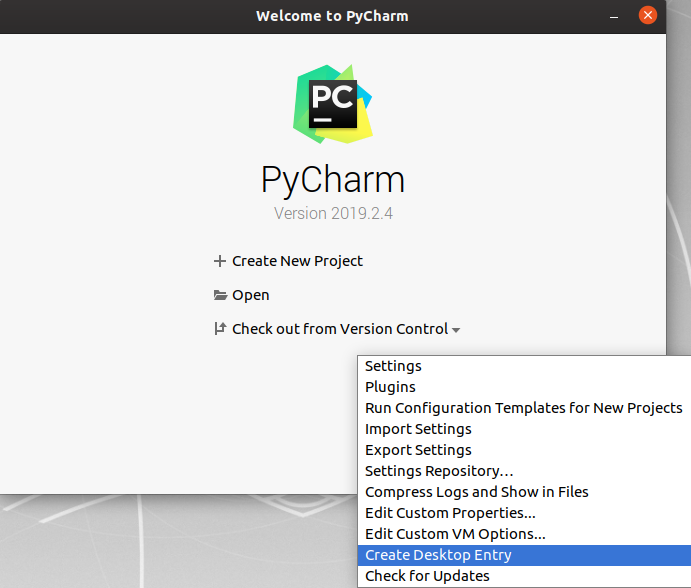

sh ./pycharm.shПроизводим установку. И очень важно в конце не забыть создать desktop файл для запуска PyCharm. Для этого в Окне приветствия в нижнем правом углу нажимаем на Configure → Create Desktop Entry.

Установка PyCharm в Ubuntu из snap-пакета

PyCharm теперь можно устанавливать из snap-пакета. Если вы используете Ubuntu 16.04 или более позднюю версию, можете установить PyCharm из командной строки.

sudo snap install pycharm-community --classicИспользование VirtualEnv и Pip в PyCharm

Поддержка Pip и Virtualenv в PyCharm появилась уже довольно давно. Иногда конечно возникают проблемы, но взаимодействие работает в основном стабильно.

Рассмотрим два варианта работы с виртуальными окружениями:

- Создаём проект со своим собственным виртуальным окружением, куда затем будут устанавливаться необходимые библиотеки;

- Предварительно создаём виртуальное окружение, куда установим нужные библиотеки. И затем при создании проекта в PyCharm можно будет его выбирать, т.е. использовать для нескольких проектов.

Первый пример: использование собственного виртуального окружения для проекта

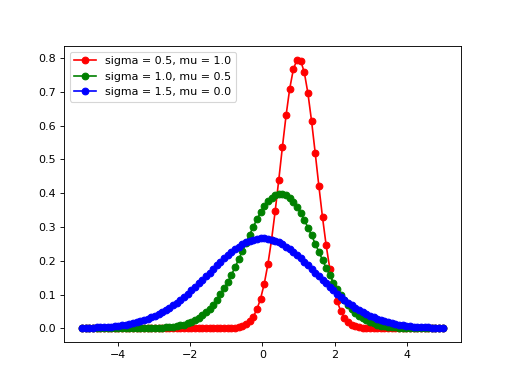

Создадим программу, генерирующую изображение с тремя графиками нормального распределения Гаусса Для этого будут использоваться библиотеки matplotlib и numpy, которые будут установлены в специальное созданное виртуальное окружение для программы.

Запускаем PyCharm и окне приветствия выбираем Create New Project.

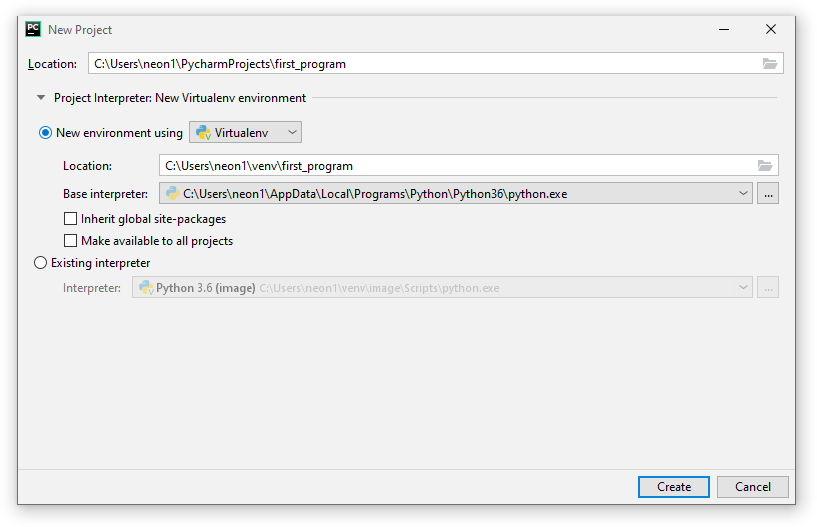

В мастере создания проекта, указываем в поле Location путь расположения создаваемого проекта. Имя конечной директории также является именем проекта. В примере директория называется ‘first_program’.

Далее разворачиваем параметры окружения, щелкая по Project Interpreter. И выбираем New environment using Virtualenv. Путь расположения окружения генерируется автоматически. В Windows можно поменять в пути папку venv на Envs, чтобы команда workon находила создаваемые в PyCharm окружения. Ставить дополнительно галочки — нет необходимости. И нажимаем на Create.

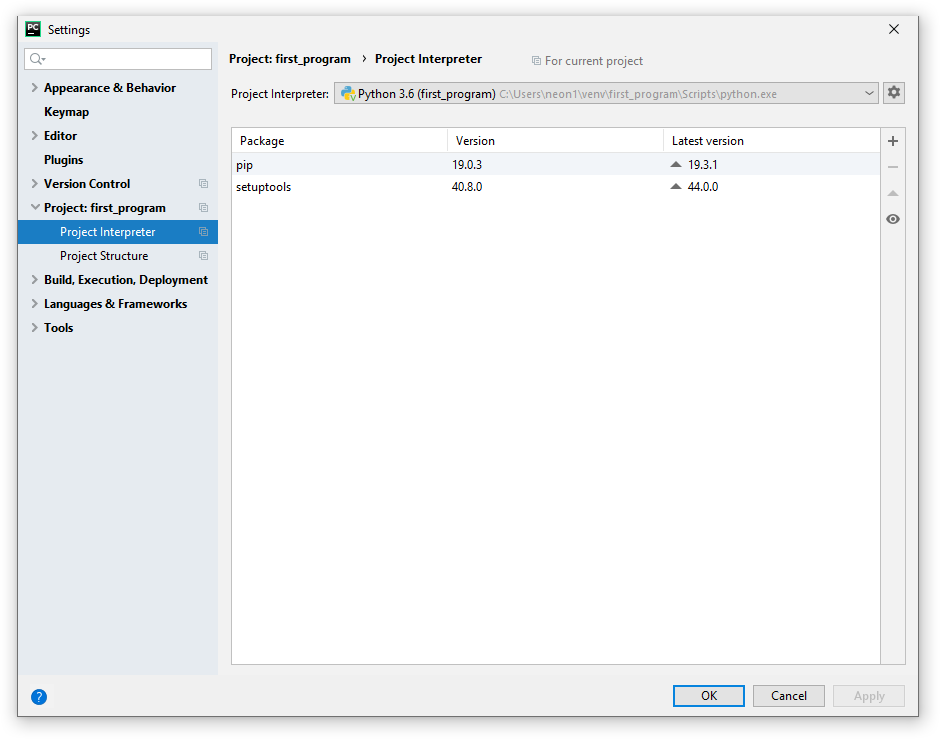

Теперь установим библиотеки, которые будем использовать в программе. С помощью главного меню переходим в настройки File → Settings. Где переходим в Project: project_name → Project Interpreter.

Здесь мы видим таблицу со списком установленных пакетов. В начале установлено только два пакета: pip и setuptools.

Справа от таблицы имеется панель управления с четырьмя кнопками:

- Кнопка с плюсом добавляет пакет в окружение;

- Кнопка с минусом удаляет пакет из окружения;

- Кнопка с треугольником обновляет пакет;

- Кнопка с глазом включает отображение ранних релизов для пакетов.

Для добавления (установки) библиотеки в окружение нажимаем на плюс. В поле поиска вводим название библиотеки. В данном примере будем устанавливать matplotlib. Дополнительно, через Specify version можно указать версию устанавливаемого пакета и через Options указать параметры. Сейчас для matplotlib нет необходимости в дополнительных параметрах. Для установки нажимаем Install Package.

После установки закрываем окно добавления пакетов в проект и видим, что в окружение проекта добавился пакет matplotlib с его зависимостями. В том, числе был установлен пакет с библиотекой numpy. Выходим из настроек.

Теперь мы можем создать файл с кодом в проекте, например, first.py. Код программы имеет следующий вид:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

x = np.linspace(-5, 5, 100)

def gauss(sigma, mu):

return 1/(sigma * (2*np.pi)**.5) * np.e ** (-(x-mu)**2/(2 * sigma**2))

dpi = 80

fig = plt.figure(dpi=dpi, figsize=(512 / dpi, 384 / dpi))

plt.plot(x, gauss(0.5, 1.0), 'ro-')

plt.plot(x, gauss(1.0, 0.5), 'go-')

plt.plot(x, gauss(1.5, 0.0), 'bo-')

plt.legend(['sigma = 0.5, mu = 1.0',

'sigma = 1.0, mu = 0.5',

'sigma = 1.5, mu = 0.0'], loc='upper left')

fig.savefig('gauss.png')Для запуска программы, необходимо создать профиль с конфигурацией. Для этого в верхнем правом углу нажимаем на кнопку Add Configuration…. Откроется окно Run/Debug Configurations, где нажимаем на кнопку с плюсом (Add New Configuration) в правом верхнем углу и выбираем Python.

Далее указываем в поле Name имя конфигурации и в поле Script path расположение Python файла с кодом программы. Остальные параметры не трогаем. В завершение нажимаем на Apply, затем на OK.

Теперь можно выполнить программу и в директории с программой появится файл gauss.png:

Второй пример: использование предварительно созданного виртуального окружения

Данный пример можно использовать во время изучения работы с библиотекой. Например, изучаем PySide2 и нам придется создать множество проектов. Создание для каждого проекта отдельного окружения довольно накладно. Это нужно каждый раз скачивать пакеты, также свободное место на локальных дисках ограничено.

Более практично заранее подготовить окружение с установленными нужными библиотеками. И во время создания проектов использовать это окружение.

В этом примере мы создадим виртуальное окружения PySide2, куда установим данную библиотеку. Затем создадим программу, использующую библиотеку PySide2 из предварительно созданного виртуального окружения. Программа будет показывать метку, отображающую версию установленной библиотеки PySide2.

Начнем с экран приветствия PyCharm. Для этого нужно выйти из текущего проекта. На экране приветствия в нижнем правом углу через Configure → Settings переходим в настройки. Затем переходим в раздел Project Interpreter. В верхнем правом углу есть кнопка с шестерёнкой, нажимаем на неё и выбираем Add…, создавая новое окружение. И указываем расположение для нового окружения. Имя конечной директории будет также именем самого окружения, в данном примере — pyside2. В Windows можно поменять в пути папку venv на Envs, чтобы команда workon находила создаваемые в PyCharm окружения. Нажимаем на ОК.

Далее в созданном окружении устанавливаем пакет с библиотекой PySide2, также как мы устанавливали matplotlib. И выходим из настроек.

Теперь мы можем создавать новый проект использующий библиотеку PySide2. В окне приветствия выбираем Create New Project.

В мастере создания проекта, указываем имя расположения проекта в поле Location. Разворачиваем параметры окружения, щелкая по Project Interpreter, где выбираем Existing interpreter и указываем нужное нам окружение pyside2.

Для проверки работы библиотеки создаем файл second.py со следующий кодом:

import sys

from PySide2.QtWidgets import QApplication, QLabel

from PySide2 import QtCore

if __name__ == "__main__":

app = QApplication(sys.argv)

label = QLabel(QtCore.qVersion())

label.show()

QtCore.qVersion()

sys.exit(app.exec_())Далее создаем конфигурацию запуска программы, также как создавали для первого примера. После чего можно выполнить программу.

Заключение

У меня нет богатого опыта программирования на Python. И я не знаком с другими IDE для Python. Поэтому, возможно, данные IDE также умеют работать с Pip и Virtualenv. Использовать Pip и Virtualenv можно в командой строке или в терминале. Установка библиотеки через Pip может завершиться ошибкой. Есть способы установки библиотек без Pip. Также создавать виртуальные окружения можно не только с помощью Virtualenv.

В общем, я лишь поделился небольшой частью опыта из данной области. Но, если не вдаваться в глубокие дебри, то этого вполне достаточно знать, чтобы писать простые программы на Python с использованием сторонних библиотек.

В данной статье мы рассмотрим, как использовать виртуальную среду для создания и управлять ими отдельно в ваших проектах Python, используя разные версии Python для выполнения, а также рассмотрим, как хранятся и разрешаются зависимости Python.

Зачем нужна виртуальная среда?

Python, как и большая часть других современных языков программирования, имеет собственный, уникальный способ загрузки, хранения и разрешения пакетов (или модулей). Это имеет свои преимущества, однако были принятые некоторые интересные решения, на счет хранения и разрешения пакетов, которые привели к определенным проблемам, а именно: как и где эти пакеты хранятся?

Содержание

- Зачем нужна виртуальная среда?

- Что такое виртуальная среда?

- Использование виртуальной среды

- Как работает виртуальная среда?

- Управление виртуальной средой при помощи virtualenvwrapper

- Использование разных версий Python

- Вывод

Существует несколько разных расположений, в которых хранятся пакеты, которые можно установить в вашей системе. Например, большая часть системных пакетов хранятся в дочернем каталоге пути, который, в свою очередь, хранится в sys.prefix.

Есть вопросы по Python?

На нашем форуме вы можете задать любой вопрос и получить ответ от всего нашего сообщества!

Telegram Чат & Канал

Вступите в наш дружный чат по Python и начните общение с единомышленниками! Станьте частью большого сообщества!

Паблик VK

Одно из самых больших сообществ по Python в социальной сети ВК. Видео уроки и книги для вас!

На Mac OS X, вы можете легко найти, где именно sys.prefix указывает на использование оболочки Python:

|

import sys print(sys.prefix) # ‘/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.5’ |

К нашей статье в большей мере относятся сторонние пакеты, установленные при помощи easy_install или pip, обычно располагаются в одном из каталогов, на которую указывает site.getsitepackages:

|

import site data = site.getsitepackages() print(data) |

Результат:

|

[ ‘/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.5/Extras/lib/python’, ‘/Library/Python/3.5/site-packages’ ] |

Зачем нам все эти детали?

Очень важно иметь представление об этом, так как по умолчанию, каждый объект вашей системы будет использовать одинаковые каталоги для хранения и разрешения пакетов (сторонних библиотек. На первый взгляд это не выглядит чем-то значительным. Это так, но только в отношении системных пакетов, являющихся частью стандартной библиотеки Python – но сторонние пакеты – это другое дело.

Представим следующий сценарий, где у вас есть два проекта: проект А и проект Б, которые оба имеют зависимость от одной и той же библиотеки – проект В. Проблема становится явной, когда мы начинаем запрашивать разные версии проекта В. Может быть так, что проект А запрашивает версию 1.0.0, в то время как проект Б запрашивает более новую версию 2.0.0, к примеру.

Это большая проблема Python, поскольку он не может различать версии в каталоге «site-packages». Так что обе версии 1.0.0 и 2.0.0 будут находиться с тем же именем в одном каталоге:

|

/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.5/Extras/lib/python/ProjectC |

И так как проекты хранятся в соответствии с их названиями, то нет различий между версиями. Таким образом, проекты А и Б должны будут использовать одну и ту же версию, что во многих случаях неприемлемо.

Тут-то и вступает в игру виртуальная среда (вместе с инструментами virtualenv/ven)

Что такое виртуальная среда?

В корне своем, главная задача виртуальной среды Python – создание изолированной среды для проектов Python.

Это значит, что:

Каждый проект может иметь свои собственные зависимости, вне зависимости от того, какие зависимости у другого проекта.

И так, в нашем небольшом примере вверху, нам просто нужно создать раздельную виртуальную среду для проектов А и Б. Каждая среда, в свою очередь, сможет зависеть от любой версии проекта В, независимо друг от друга.

Это хорошо тем, что у нас нет ограничений на то, в скольких экземплярах будет наша виртуальная среда, так как они являются обычными каталогами, в которых содержится несколько скриптов. Плюс, их очень легко создать при помощи инструментов командной строки virtualenv или pyenv.

Использование виртуальной среды

Перед тем, как начать: если вы не пользуетесь Python 3, вам нужно будет установить инструмент virtualenv при помощи pip:

Если вы используете Python 3, у вас уже должен быть модуль venv, установленный в стандартной библиотеке.

Предположим, что вы пользуетесь последней версией инструмента venv, так как между ним и virtualenv существует несколько различий в отношении команд. По большому счету, это два весьма разных инструмента.

Начнем с создания нового каталога, с которым мы будем работать:

|

mkdir python—virtual—environments && cd python—virtual—environments |

Создание новой виртуальной среды внутри каталога:

|

# Python 2: $ virtualenv env # Python 3 $ python3 —m venv env |

По умолчанию, это не включает в себя ни один из существующих сторонних пакетов.

Подход venv в Python 3 обладает преимуществом, которое вынуждает вас использовать определенную версию интерпретатора Python 3, который будет использован для создания виртуальной среды. Таким образом, вы избегаете недоразумений при выяснении, какая инсталляция Python базируется в новой виртуальной среде.

Начиная с Python 3.3 и 3.4, рекомендуемый способ создания виртуального пространства – это использование инструмента командной строки pyvenv, который также включен в инсталляцию вашего Python 3 по умолчанию. Однако, в версии 3.6 и выше, вам нужен python3 -m venv.

В примере выше, эта команда создает каталог под названием «env», структура каталога которого схожа со следующей:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

├── bin │ ├── activate │ ├── activate.csh │ ├── activate.fish │ ├── easy_install │ ├── easy_install—3.5 │ ├── pip │ ├── pip3 │ ├── pip3.5 │ ├── python -> python3.5 │ ├── python3 -> python3.5 │ └── python3.5 -> /Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.5/bin/python3.5 ├── include ├── lib │ └── python3.5 │ └── site—packages └── pyvenv.cfg |

Что находится в этих папках?

- bin – файлы, которые взаимодействуют с виртуальной средой;

- include – С-заголовки, компилирующие пакеты Python;

- lib – копия версии Python вместе с папкой «site-packages», в которой установлена каждая зависимость.

Далее, у нас есть копии или символические ссылки нескольких различных инструментов Python. Эти файлы используются для обеспечения того, чтобы команды и код Python выполнялись в контексте нынешней среды, таким образом, достигается изоляция от глобальной среды. Мы рассмотрим это детальнее в следующем разделе.

Более интересные сейчас – скрипты activate в папке bin. Эти скрипты используются для настройки вашей оболочки для использования исполняемого файла среды Python и его сайтовых пакетов по умолчанию.

Чтобы использовать эти пакеты (или ресурсы) среды в изоляции, вам нужно «активировать» их. Чтобы сделать это, просто запустите:

Обратите внимание на то, что ваше приглашение командной строки теперь носит префикс вашей среды (в нашем случае – env). Это индикатор того, что env в данный момент активен, что в свою очередь говорит о том, что выполнимые файлы Python используют пакеты и настройки только этой среды.

Чтобы показать изолированный пакет в действии, мы можем использовать модуль bcrypt в качестве примера. Скажем, что модуль bcrypt установлен где-нибудь в системе, но не в нашей виртуальной среде.

Перед тем как проверить это, нам нужно вернуться назад в контекст «system» , выполнив команду deactivate:

Теперь ваш сеанс оболочки вернулся в норму, а команда python ссылается на общую установку Python. Помните: это можно делать когда угодно, после закрытия определенной виртуальной среды.

Теперь установим bcrypt и используем его для хеширования пароля:

|

$ pip —q install bcrypt $ python —c «import bcrypt; print(bcrypt.hashpw(‘password’.encode(‘utf-8’), bcrypt.gensalt()))» $2b$12$vWa/VSvxxyQ9d.WGgVTdrell515Ctux36LCga8nM5QTW0.4w8TXXi |

Что произойдет, если мы попробуем ту же команду, когда виртуальная среда активна?

|

$ source env/bin/activate (env) $ python —c «import bcrypt; print(bcrypt.hashpw(‘password’.encode(‘utf-8’), bcrypt.gensalt()))» Traceback (most recent call last): File «<string>», line 1, in <module> ImportError: No module named ‘bcrypt’ |

Как мы видим, поведение команды the python -c «import bcrypt…» меняется после вызова источника env/bin/activate.

В одном примере, у нас есть доступный нам bcrypt, а в другом его нет. Это тот тип разделения, который мы ищем для виртуальной среды, и мы к нему пришли.

Как работает виртуальная среда?

Что именно имеется ввиду под «активировать» среду? Понимание того, что именно происходит под капотом, может быть очень важно для разработчика, особенно когда вам нужно понять выполнение виртуальной среды, разрешение зависимостей, и так далее.

Чтобы объяснить, как это работает, для начала проверим расположения разных исполняемых файлов python. С «деактивированной» средой запускаем:

|

$ which python /usr/bin/python |

Теперь активируем и снова запустим команду:

|

$ source env/bin/activate (env) $ which python /Users/michaelherman/python—virtual—environments/env/bin/python |

Активировав среду, мы теперь получаем другой путь к исполнимому файлу python, так как в активной среде, переменная среды $PATH несколько отличается.

Обратите внимание на разницу между первым путем в $PATH до и после активации:

|

$ echo $PATH /usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/sbin:/sbin: $ source env/bin/activate (env) $ echo $PATH /Users/michaelherman/python—virtual—environments/env/bin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/sbin:/sbin: |

В последнем примере, каталог bin нашей виртуальной среды теперь находится в начале пути. Это значит, что это первый каталог в поиске, когда мы запускаем исполняемый файл в командной строке. Таким образом, оболочка использует экземпляр нашей виртуальной среды в Python, а не в системной версии.

Другие пакеты, связывающие Python, такие как Anaconda, также могут выполнять манипуляции с вашим путем, если вы активируете их. Просто имейте это ввиду на случай, если вы столкнетесь с проблемами, связанными с другими виртуальными средами. Проблема может возникнуть при активации нескольких сред одновременно.

Это наталкивает на вопросы:

- В чем разница между этими исполняемыми файлами?

- Каким образом виртуальная среда исполняемого файлаPython может использовать что-либо, кроме системных сайт-пакетов?

Это можно объяснить тем, как Python запускается и где он расположен в системе. Нет разницы между двумя исполняемыми файлами Python. Суть заключается в расположении каталога

Когда Python запускается, он ищет путь своего двоичного файла (в виртуальной среде он является копией или символической ссылке системного бинарного файла Python). Далее, он устанавливает расположение sys.prefix и sys.exec_prefix согласно с этим расположением, опуская часть bin в пути.

Путь, находящийся в sys.prefix далее используется для поиска каталога site-packages, путем поиска по связанного с ним пути lib/pythonX.X/site-packages/, где Х.Х – это версия используемого вами Python.

В нашем примере, бинарный файл расположен в /Users/michaelherman/python-virtual-environments/env/bin, это значит, что sys.prefix может быть /Users/michaelherman/python-virtual-environments/env, следовательно, используемый каталог site-packages может быть /Users/michaelherman/python-virtual-environments/env/lib/pythonX.X/site-packages. Наконец, этот путь наложен в массиве sys.path, который содержит все расположения, которые пакет может использовать.

Управление виртуальной средой при помощи virtualenvwrapper

Несмотря на то, что виртуальная среда определенно решает ряд проблем с управлением пакетами, она не идеальна. После создания нескольких виртуальных сред, вы обнаружите, что они создают некоторые проблемы сами по себе, большая часть которых вращается вокруг управления самими виртуальными средами. Чтобы помочь с этим, был создан инструмент virtualenvwrapper, который представляет собой набор оберточных скриптов вокруг основного инструмента virtualenv.

Самые полезные функции virtualenvwrapper:

- Организация каждой виртуальной среды в одном расположении;

- Предоставляются методы, которые помогут вам легко создавать, удалять и копировать виртуальную среду, а также,

- Предоставляет одну команду для переключения между средами

Некоторые функции могут показаться узкими, или незначительными, вы быстро поймете, что они – это отличные инструменты для вашего рабочего ритма.

Перед началом, вы можете скачать обёртку при помощи pip:

|

$ pip install virtualenvwrapper |

Для Windows нужно использовать virtualenvwrapper-win

После завершения установки, нам нужно активировать его функции оболочки. Это можно сделать, запустив источник установленного скрипта virtualenvwrapper.sh. Кода вы в первый раз устанавливаете его при помощи pip, выдача установки укажет вам точное расположение virtualenvwrapper.sh. Впрочем, вы можете просто запустить команду:

|

$ which virtualenvwrapper.sh /usr/local/bin/virtualenvwrapper.sh |

Используя данный путь, добавьте следующие три строки в стартовый файл вшей оболочки. Если оболочку Bash, вы можете разместить эти строки и в файле ~/.bashrc file or ~/.profile. Для других оболочек, таких как zsh, csh или fish, вам может понадобиться определенные файлы запуска для этой оболочки. Главное, чтобы эти команды выполнялись при открытии новой оболочки или входе в неё.

|

export WORKON_HOME=$HOME/.virtualenvs # optional export PROJECT_HOME=$HOME/projects # optional source /usr/local/bin/virtualenvwrapper.sh |

От нас не требуется определять переменные виртуальной среды WORKON_HOME и PROJECT_HOME. В virtualenvwrapper имеются установленные по умолчанию переменные для них, но вы можете перезаписать их, указав значения.

Наконец, перезагружаем файл запуска:

Теперь здесь должен быть каталог, расположенный в $WORKON_HOME, который содержит все данные и файлы virtualenvwrapper:

|

$ echo $WORKON_HOME /Users/michaelherman/.virtualenvs |

Кроме этого, у вас теперь в распоряжении имеются доступные команды оболочки, которые помогут в управлении виртуальной средой. Вот несколько из них:

- workon

- deactivate

- mkvirtualenv

- cdvirtualenv

- rmvirtualenv

Для дополнительной информации о командах, установке и настройке virtualenvwrapper, вы можете ознакомиться с их документацией.

Теперь, когда бы вы не начинали новый проект, все что вам нужно, это:

|

$ mkvirtualenv my—new—project (my—new—project) $ |

Это создаст и активирует новую виртуальную среду в каталоге, расположенном в $WORKON_HOME, где хранятся все среды virtualenvwrapper.

Чтобы прекратить использование этой среды, вам всего лишь нужно её деактивировать, как мы делали это раньше:

|

(my—new—project) $ deactivate $ |

Если у вас есть широкий выбор виртуальных сред, вы можете отсортировать их по списку при помощи функции workon:

|

$ workon my—new—project my—django—project web—scraper |

И, наконец, активировать:

|

$ workon web—scraper (web—scraper) $ |

Если вы хотите иметь один инструмент и переключаться между версиями Python, virtualenv позволит вам это сделать. Virtualenv содержит параметр -р, который позволяет вам выбрать, какую версию Python использовать. Совместите это с командой which, и мы можем быстро выбрать предпочитаемую версию Python. К примеру, скажем, что мы хотим выбрать Python 3 в качестве нашей основной версии:

|

$ virtualenv —p $(which python3) blog_virtualenv |

Это создаст новую среду python3.

Так как же это работает? Команда which используется для поиска переданной команды в вашей переменной $PATH и возвращает полный путь к этой команде. Так, полный путь к Python3 вернулся параметру -р , который в свою очередь принимает PYTHON_EXE. Это также можно практиковать и в Python2. Просто замените python3 на python2 (или python, если вы используете python2 по умолчанию).

Теперь вам не нужно помнить где вы установили вашу виртуальную среду. Вы можете просто удалить или копировать ее как хотите, разгрузив ваш проектный каталог.

В отличие от старого virtualenv, pyvenv не поддерживает создание виртуальной среды в произвольных версиях Python. Это значит, что вам придется использовать установленный Python 3 по умолчанию для каждой создаваемой вами виртуальной среды. Хотя вы можете обновить среду до последней системной версии Python (через опцию –upgrade) если она поменялась, вы все еще не можете указывать конкретную версию.

Существует предостаточно способов установить Python, но только некоторые из них достаточно простые или гибкие, чтобы повторно удалять и переустанавливать разные бинарные версии файлов.

Здесь и вступает в игру pyenv.

Несмотря на схожесть в названиях (pyvenv и pyenv), pyenv отличается тем, что он направлен на то, чтобы помочь переключаться между версиями Python на как на системном уровне, так и на проектном. Другими словами, задача pyvenv разделять модули, задача pyenv – разделять версии Python.

Вы можете начать с установки pyenv как при помощи Homebrew (на OS X), или при помощи проекта pyenv-installer:

Homebrew

pyenv-installer

|

$ curl —L https://raw.githubusercontent.com/yyuu/pyenv—installer/master/bin/pyenv—installer | bash |

К сожалению, pyenv не поддерживается Windows. Вы можете воспользоваться альтернативами в виде pywin и anyenv.

После установки pyenv в вашей системе, есть несколько базовых команд, которые вас могут заинтересовать:

КОД # Install new version установка новой версии

КОД # Внесение установленных версий в список

КОД # Выполнение «python-V» с использованием версии pyenv

|

$ pyenv install 3.5.0 # Установка новой версии $ pyenv versions # Внесение установленных версий в список $ pyenv exec python —V # Выполнение «python-V» с использованием версии pyenv |

Этими тремя строками мы устанавливаем версию Python 3.5.0, просим pyenv показать все доступные нам версии, после чего выполнить команду python –V, используя определенную pyenv версию.

Чтобы дать вам больше контроля, вы можете использовать любую доступную версию как для «глобального», так и «локального». Использование pyenv с локальными командами настраивает версию Python на определенный проект или директорию, сортируя версию в локальном файле .python-version. Мы можем настроить «локальную» версию следующим образом:

Это создает файл .python-version в нашем текущем каталоге, как вы можете видеть здесь:

|

$ ls —la total 16 drwxr—xr—x 4 michaelherman staff 136 Feb 22 10:57 . drwxr—xr—x 9 michaelherman staff 306 Jan 27 20:55 .. —rw—r—r— 1 michaelherman staff 7 Feb 22 10:57 .python—version —rw—r—r— 1 michaelherman staff 52 Jan 28 17:20 main.py |

Этот файл содержит только «2.7.11». Теперь, когда вы запускаете скрипт при помощи pyenv, он загрузит этот файл, и использует определенную версию, предполагая, что он действителен и существует в вашей системе.

Двигаясь дальше с нашим примером, предположим, что у нас есть простой скрипт, под названием main.py в нашем проектном каталоге, который выглядит следующим образом:

|

import sys print(‘Using version:’, sys.version[:5]) |

Все что он делает, это выводит номер версии используемого выполняемого файла Python. При помощи pyenv и команды exec, мы можем запустить скрипт с любой другой установленной версией Python.

|

$ python main.py Using version: 2.7.5 $ pyenv global 3.5.0 $ pyenv exec python main.py Using version: 3.5.0 $ pyenv local 2.7.11 $ pyenv exec python main.py Using version: 2.7.11 |

Обратите внимание на то, как pyenv exec python main.py использует нашу «глобальную» версию Python по умолчанию, но затем он использует «локальную» версию после ее установки в текущий каталог.

Это может быть мощным орудием для разработчиков, работающих со множеством проектов с различными требованиями к версии. Вы можете не только изменить версию по умолчанию для всех проектов (через global), но также переопределять ее для указания особых случаев.

Вывод

В данной статье вы узнали больше о том, как хранятся и разрешаются зависимости Python, как использовать различные инструменты для помощи в обходе различных проблем, связанных с пакетами и версиями.

Как вы видите, благодаря огромному сообществу Python, в вашем распоряжении имеется обширное количество инструментов для помощи с решением этих проблем. С вашим ростом в качестве разработчика, убедитесь, что вы уделили время тому, как использовать эти инструменты в своих интересах. Вы даже можете найти особенное использование для них, или применять схожие концепции в других языках программирования, которые вы используете.

Являюсь администратором нескольких порталов по обучению языков программирования Python, Golang и Kotlin. В составе небольшой команды единомышленников, мы занимаемся популяризацией языков программирования на русскоязычную аудиторию. Большая часть статей была адаптирована нами на русский язык и распространяется бесплатно.

E-mail: vasile.buldumac@ati.utm.md

Образование

Universitatea Tehnică a Moldovei (utm.md)

- 2014 — 2018 Технический Университет Молдовы, ИТ-Инженер. Тема дипломной работы «Автоматизация покупки и продажи криптовалюты используя технический анализ»

- 2018 — 2020 Технический Университет Молдовы, Магистр, Магистерская диссертация «Идентификация человека в киберпространстве по фотографии лица»

Продолжаем серию “Python.Уроки”. На этот раз мы изучим, что такое виртуальные окружения в Python, зачем они нужны и как их использовать. Познакомимся с инструментами virtualenv и venv для создания виртуальных окружений.

- Что такое виртуальное окружение и зачем оно нужно?

- ПО позволяющее создавать виртуальное окружение в Python

- virtualenv

- Установка virtualenv

- Создание виртуального окружения

- Активация виртуального окружения

- Деактивация виртуального окружения

- venv

- Создание виртуального окружения

- Активация виртуального окружения

- Деактивация виртуального окружения

- Полезные ссылки

Что такое виртуальное окружение и зачем оно нужно?

При разработке Python-приложений или использовании решений на Python, созданных другими разработчиками, может возникнуть ряд проблем, связанных с использованием библиотек различных версий. Рассмотрим их более подробно.

Во-первых: различные приложения могут использовать одну и туже библиотеку, но при этом требуемые версии могут отличаться.

Во-вторых: может возникнуть необходимость в том, чтобы запретить вносить изменения в приложение на уровне библиотек, т.е. вы установили приложение и хотите, чтобы оно работало независимо от того обновляются у вас библиотеки или нет. Как вы понимаете, если оно будет использовать библиотеки из глобального хранилища (/usr/lib/pythonXX/site-packages), то, со временем, могут возникнуть проблемы.

В-третьих: у вас просто может не быть доступа к каталогу /usr/lib/pythonXX/site-packages.

Для решения данных вопросов используется подход, основанный на построении виртуальных окружений – своего рода песочниц, в рамках которых запускается приложение со своими библиотеками, обновление и изменение которых не затронет другие приложение, использующие те же библиотеки.

Программное обеспечение, которое позволяет создавать виртуальные окружения в Python можно разделить на те, что входят в стандартную библиотеку Python и не входят в нее. Сделаем краткий обзор доступных инструментов (хороший пост на эту тем есть на stackoverflow).

Начнем с инструментов, которые входят в PyPI. Если кто не знает PyPI – это Python Package Index (PyPI) – репозиторий пакетов Python, доступный для любого разработчика и пользователя Python ().

virtualenv

Это, наверное, одни из самых популярных инструментов, позволяющих создавать виртуальные окружения. Он прост в установке и использовании. В сети довольно много руководств по virtualenv, самые интересные, на наш взгляд, будут собраны в конце урока в разделе “Полезные ссылки”. В общем, этот инструмент нужно обязательно освоить, как минимум, потому что описание развертывания и использования многих систем, созданных с использованием Python, включает в себя процесс создания виртуального окружения с помощью virtualenv.

pyenv

Инструмент для изоляции версий Python. Чаще всего применяется, когда на одной машине вам нужно иметь несколько версий интерпретатора для тестирования на них разрабатываемого вами ПО.

virtualenvwrapper

Virtualenvwrapper – это обертка для virtualenv позволяющая хранить все изолированные окружения в одном месте, создавать их, копировать и удалять. Предоставляет удобный способ переключения между окружениями и возможность расширять функционал за счет plug-in’ов.

Существуют ещё инструменты и plug-in’ы, выполняющие работу по изоляции частей системы Python, но мы их не будем рассматривать.

Инструменты, входящие в стандартную библиотеку Python.

venv

Этот модуль появился в Python3 и не может быть использован для решения задачи изоляции в Python2. По своему функционалу очень похож на virtualenv. Если вы работаете с третьим Python, то можете смело использовать данный инструмент.

virtualenv

Будем рассматривать работу с virtualenv в рамках операционной системы Linux. Для Windows все будет очень похоже, за исключением моментов, связанных со спецификой этой ОС: названия и расположение каталогов, запуск скриптов оболочки и т.п.

Установка virtualenv

Virtualenv можно установить с использованием менеджера pip (ссылка на статью), либо скачать исходные коды проекта и установить приложение вручную.

Установка с использованием pip.

Для установки virtualenv откройте консоль и введите следующую команду:

> pip install virtualenv

Установка из исходного кода проекта.

В этом случае, вам нужно будет выполнить чуть большее количество действий.

Введите в консоли следующий набор команд:

> curl -O https://pypi.python.org/packages/source/v/virtualenv/virtualenv-X.X.tar.gz > tar xvfz virtualenv-X.X.tar.gz > cd virtualenv-X.X > [sudo] python setup.py install

X.X – это версия приложения, ее вам нужно знать заранее.

Если использовать ключевое слово sudo, инструмент будет установлен глобально, в противном случае – локально.

Мы рекомендуем вам использовать pip для установки virtualenv.

Создание виртуального окружения

Виртуальное окружение создается следующей командой:

> virtualenv PRG1

PRG1 в данном случае – это имя окружения.

После выполнения данной команды, в текущем каталоге будет создан новый каталог с именем PRG1. Разберем более подробно его содержимое.

RPG1/bin/ – содержит скрипты для активации/деактивации окружения, интерпретатор Python, используемый в рамках данного окружения, менеджер pip и ещё несколько инструментов, обеспечивающих работу с пакетами Python. В Windows, это каталог PRG1Scripts

PRG1/include/ и PRG1/lib/ – каталоги, содержащие библиотечные файлы окружения. Новые пакеты будут установлены в каталог PRG1/lib/pythonX.X/site-packages/.

Активация виртуального окружения

Для активации виртуального окружения воспользуйтесь командой (для Linux):

> source PRG1/bin/activate

для Windows команда будет выглядеть так:

> PRG1Scriptsactivate.bat

Команда source выполняет bash-скрипт без запуска второго bash-процесса.

Если команда выполнилась успешно, то вы увидите, что перед приглашением в командной строке появилась дополнительная надпись, совпадающая с именем виртуального окружения.

При этом в переменную окружения PATH, в самое начало, будет добавлен путь до директории bin, созданного каталога RPG1.

Если вы создадите виртуальное окружение с ключем –system-site-packages:

> virtualenv --system-site-packages PRG1

то в рамках окружения PRG1 вы будите иметь доступ к глобальному хранилищу пакетов:

-

- в Linux: /usr/lib/pythonX.X/site-packages

- в Windows: PythonXXLibsite-packages

Деактивация виртуального окружения

Для деактивации виртуального окружения (выхода из него), введите команду deactivate для Linux или deactivate.bat, если вы работаете в Windows.

> deactivate

venv

Устанавливать venv не нужно, т.к. он входит в стандартную библиотеку Python. Т.е. если вы установили себе Python, то venv у вас уже есть. Помните, что venv работает только в Python3!

Создание виртуального окружения

Для создания виртуального окружения с именем PRG2 с помощью venv выполните следующую команду:

> python -m venv PRG2

В результате будет создан каталог PRG2 со структурой похожей на ту, что была описана для virtualenv. Функциональное назначение каталогов тоже самое.

Активация виртуального окружения

Активация виртуального окружения в Linux выполняется командой:

>source PRG2/bin/activate

в Windows:

>PRG2Scriptsactivate.bat

Деактивация виртуального окружения

Деактивация выполняется командой deactivate (работает как в Windows, так и в Linux)

>deactivate

Полезные ссылки

Ниже приведен список полезных ссылок, для того, чтобы более глубоко изучить тему создания виртуальных окружений в Python.

Официальная документация

Документация по virtualenv

Документация по virtualenvwrapper

Документация по venv

Статьи

Python. Строим виртуальное окружение с помощью virtualenv

Памятка по virtualenv и изолированным проектам на Python

P.S.

Если вам интересна тема анализа данных, то мы рекомендуем ознакомиться с библиотекой Pandas. На нашем сайте вы можете найти вводные уроки по этой теме. Все уроки по библиотеке Pandas собраны в книге “Pandas. Работа с данными”.

<<< Python. Урок 16. Установка пакетов в Python Python. Урок 18. Аннотация типов в Python>>>

virtualenv — это инструмент для создания изолированной среды Python. У такой среды есть отдельна установка python, при ее использовании загруженные библиотеки недоступны другим. Можно сделать так, чтобы у этой среды не было доступа к глобальным библиотекам.

Virtualenv — простой и рекомендованный способ настройки среды Python.

Отличия virtualenv и venv

Venv — это пакет, который идет по умолчанию с Python 3.3+. В версии Python 2 его нет.

Virtualenv — более продвинутая библиотека. По ссылке можно ознакомиться с основными отличиями.

Виртуальную среду можно создать и с помощью venv, но все-таки рекомендуется установить и использовать virtualenv для полноценной работы.

Для установки virtualenv с Python нужно использовать pip. Желательно предварительно обновить этот инструмент.

python -m pip install --upgrade pipИли используйте python3, если python ссылается на 2 версию.

После обновления можно установить и virtualenv:

pip install virtualenv # или pip3Создание виртуальной среды

1. Перейдите в директорию, в которой вы хотите создать виртуальную среду(например папка проекта).

~$ cd test

~/test$2. Создайте виртуальную среду, при необходимости указав конкретную версию Python. Следующая команда создает virtualenv с именем venv_name и использует флаг -p, чтобы указать полный путь к версии Python:

virtualenv -p /usr/bin/python venv_name

# или

virtualenv venv_nameНазвать среду можно как угодно

После выполнения команды вы увидите логи:

Running virtualenv with interpreter /usr/bin/python

Already using interpreter /usr/bin/python

Using base prefix '/usr'

New python executable in /home/username/test/venv_name/bin/python

Installing setuptools, pip, wheel...

done.Эта команда создает локальную копию среды. Работая с ней, важно не забывать об активации, чтобы использовались нужные версии конкретных инструментов и пакетов.

Если при установке возникла ошибка setuptools pip failed with error code 1` error, используйте следующую команду, чтобы решить проблему:

pip install --upgrade setuptools # или pip33. Для активации новой виртуальной среды используйте команду:

source venv_name/bin/activateПосле этого название текущей среды отобразится слева от символа ввода: (venv_name) username@desctop:~/test$

Теперь при установке любого пакета с помощью pip он будет размещаться в папках этой среды, изолированно от глобальной установки.

Деактивации virtualenv

После завершения работы деактивировать виртуальную среду можно с помощью команды deactivate.

Введите ее и приставка venv_name пропадет. Вы вернетесь к использованию глобально версии python.

Удаление виртуальной среды

Для удаления виртуальной среды достаточно просто удалить папку проекта. Для этого используется следующая команда:

rm -rf venv_nameРешение популярных ошибок

Ошибки при создании virtualenv. При попытке создать virtualenv с Python 3.7 могут возникнуть следующие ошибки.

AttributeError: module 'importlib._bootstrap' has no attribute 'SourceFileLoader'

OSError: Command /home/username/venv/bin/python3 -c "import sys, pip; sys...d"] + sys.argv[1:]))" setuptools pip failed with error code 1Для их исправления нужно добавить следующую строку в .bash_profile.

export LC_ALL="en_US.UTF-8"Использование полного пути к виртуальной среде. Может быть такое, что при использовании команды virtualenv будет использована не та версия. Для решения проблемы нужно лишь задать полные пути как к virtualenv, так и к Python в системе.

А получить их можно с помощью этой команды:

/home/username/opt/python-3.8.0/bin/virtualenv -p /home/username/opt/python-3.8.0/bin/python3 venvЕсли вы работали с несколькими проектами, в которых использовался Python, то наверняка вы встречались с проблемой поломки одного из проекта, потому что обновленная версия библиотеки для другого проекта, не применима для текущего. Т.е. если вы работаете с Python и не используете miniconda или anaconda, то установка и обновление библиотек python постоянно ломает ваши проекты. Эта проблема называется «Ад зависимостей».

Поэтому лучшим подходом будет создавать для каждого отдельного проекта свою среду. В этой статье будет рассмотрена библиотека venv для настройки Virtual Environment для Windows.

Виртуальная среда — это способ Python для разделения зависимостей между проектами.

Создание виртуальной среды — venv в Windows

venv -это пакет, поставляемый с Python 3.

venv (для Python 3) позволяет управлять отдельными установками пакетов для разных проектов. По сути, venv позволяет вам создавать «виртуальную» изолированную установку Python и устанавливать пакеты в эту виртуальную установку. При переключении проектов вы можете просто создать новую виртуальную среду и не беспокоиться о нарушении работы пакетов, установленных в других средах. При разработке приложений Python всегда рекомендуется использовать виртуальную среду.

Чтобы создать виртуальную среду, перейдите в каталог вашего проекта и запустите venv.

python3 -m venv venv

или

python -m venv venv

venv создаст виртуальную установку Python в директории venv.

Примечание: Вы должны исключить каталог виртуальной среды из своей системы управления версиями с помощью

.gitignore.

Активация и деактивация виртуальной среды Python

Далее необходимо активировать виртуальную среду.

Для этого необходимо в консоли cmd запустить .venvScriptsactivate или файл .venvScriptsactivate.bat, или .venvScriptsActivate.ps1.

Префикс вашего рабочего каталога изменится (выделил желтым — venv)

Пока ваша виртуальная среда активирована, pip будет устанавливать пакеты в эту конкретную среду, и вы сможете импортировать и использовать пакеты в своем приложении Python.

Установка пакетов в виртуальную среду

Пример:

pip install requests

pip позволяет вам указать, какую версию пакета установить, используя спецификаторы версии. Например, чтобы установить определенную версию requests:

pip install requests==2.18.4

Как сохранить пакеты в файл requirements.txt

Pip может экспортировать список всех установленных пакетов и их версий с помощью freeze команды: pip freeze > requirements.txt.

Будет выведен список спецификаторов пакетов, таких как:

backports.entry-points-selectable==1.1.0 certifi==2021.5.30 charset-normalizer==2.0.3 distlib==0.3.2 filelock==3.0.12 idna==3.2 platformdirs==2.0.2 requests==2.26.0 six==1.16.0 urllib3==1.26.6 virtualenv==20.6.0

Имейте в виду, что в этом случае в файле requirements.txt будут перечислены все пакеты, которые были установлены в виртуальной среде, независимо от того, откуда они пришли.

Установить пакеты из файла requirements.txt

pip install -r requirements.txt

Как запустить скрипт Python в виртуальной среде. Пример автоматизации с помощью cmd

Для того, чтобы запустить скрипт, достаточно внутри директории с проектом (со средой) запустить команду:

"D:#python##envflask-appvenvScriptspython.exe" "D:#python##envflask-appapp.py"

Либо создать файл cmd с содержимым и запустить его:

@echo off

For /f "tokens=1-4 delims=/ " %%a in ('date /t') do (set mydate=%%c-%%a-%%b)

For /f "tokens=1-2 delims=/:" %%a in ('time /t') do (set mytime=%%a%%b)

rem %mydate%_%mytime%

"D:#python##envflask-appvenvScriptspython.exe" "D:#python##envflask-appapp.py" 2>"D:#python##envflask-applog_get_data_log_%mydate%_%mytime%.log"

Создание виртуальной среды с помощью PyCharm

Для более легкой работы с виртуальными средами на Windows рекомендую установить PyCharm (Community Edition бесплатная). При создании проекта он сам создаст виртуальную среду и будет запускать файл в этой виртуальной среде:

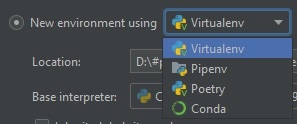

Новую виртуальную среду можно создать с помощью разных инструментов в Pycharm:

- Virtualenv

- Pipenv

- Poetry

- Conda

Создание виртуальной среды в Ubuntu 20.14

С помощью пакета venv

# Создаем директорию проекта mkdir flask-app # Переходим внутрь директории cd flask-app # Создаем среду myenv python3 -m venv myenv # Активируем среду source myenv/bin/activate

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Working With Python Virtual Environments

In this tutorial, you’ll learn how to work with Python’s venv module to create and manage separate virtual environments for your Python projects. Each environment can use different versions of package dependencies and Python. After you’ve learned to work with virtual environments, you’ll know how to help other programmers reproduce your development setup, and you’ll make sure that your projects never cause dependency conflicts for one another.

By the end of this tutorial, you’ll know how to:

- Create and activate a Python virtual environment

- Explain why you want to isolate external dependencies

- Visualize what Python does when you create a virtual environment

- Customize your virtual environments using optional arguments to

venv - Deactivate and remove virtual environments

- Choose additional tools for managing your Python versions and virtual environments

Virtual environments are a common and effective technique used in Python development. Gaining a better understanding of how they work, why you need them, and what you can do with them will help you master your Python programming workflow.

Throughout the tutorial, you can select code examples for either Windows, Ubuntu Linux, or macOS. Pick your platform at the top right of the relevant code blocks to get the commands that you need, and feel free to switch between your options if you want to learn how to work with Python virtual environments on other operating systems.

How Can You Work With a Python Virtual Environment?

If you just need to get a Python virtual environment up and running to continue working on your favorite project,

then this section is the right place for you.

The instructions in this tutorial use Python’s venv module to create virtual environments.

This module is part of Python’s standard library, and it’s the officially recommended way to create virtual environments since Python 3.5.

For basic usage, venv is an excellent choice because it already comes packaged with your Python installation. With that in mind, you’re ready to create your first virtual environment in this tutorial.

Create It

Any time you’re working on a Python project that uses external dependencies that you’re installing with pip,

it’s best to first create a virtual environment:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

If you’re using Python on Windows

and you haven’t configured the PATH and PATHEXT variables,

then you might need to provide the full path to your Python executable:

PS> C:UsersNameAppDataLocalProgramsPythonPython310python -m venv venv

The system path shown above assumes that you installed Python 3.10 using the Windows installer provided by the Python downloads page. The path to the Python executable on your system might be different. Working with PowerShell, you can find the path using the where.exe python command.

Many Linux operating systems ship with a version of Python 3.

If python3 doesn’t work, then you’ll have to first install Python, and you may need to use the specific name of the executable version that you installed, for example python3.10 for Python 3.10.x. If that’s the case for you, remember to replace mentions of python3 in the code blocks with your specific version number.

Older versions of macOS come with a system installation of Python 2.7.x that you should never use to run your scripts. If you’re working on macOS < 12.3 and invoke the Python interpreter with python instead of python3, then

you might accidentally start up the outdated system Python interpreter.

If running python3 doesn’t work, then you’ll have to first install a modern version of Python.

Activate It

Great! Now your project has its own virtual environment. Generally, before you start using it, you’ll first activate the environment by executing a script that comes with the installation:

- Windows

- Linux + macOS

PS> venvScriptsactivate

(venv) PS>

$ source venv/bin/activate

(venv) $

Before you run this command, make sure that you’re in the folder that contains the virtual environment you just created.

Once you can see the name of your virtual environment—in this case (venv)—in your command prompt, then you know that your virtual environment is active. You’re all set and ready to install your external packages!

Install Packages Into It

After creating and activating your virtual environment, you can now install any external dependencies that you need for your project:

- Windows

- Linux + macOS

(venv) PS> python -m pip install <package-name>

(venv) $ python -m pip install <package-name>

This command is the default command that you should use to install external Python packages with pip. Because you first created and activated the virtual environment, pip will install the packages in an isolated location.

Congratulations, you can now install your packages to your virtual environment. To get to this point, you began by creating a Python virtual environment named venv and then activated it in your current shell session.

As long as you don’t close your terminal, every Python package that you’ll install will end up in this isolated environment instead of your global Python site-packages. That means you can now work on your Python project without worrying about dependency conflicts.

Deactivate It

Once you’re done working with this virtual environment, you can deactivate it:

- Windows

- Linux + macOS

(venv) PS> deactivate

PS>

After executing the deactivate command, your command prompt returns to normal.

This change means that you’ve exited your virtual environment. If you interact with Python or pip now, you’ll interact with your globally configured Python environment.

If you want to go back into a virtual environment that you’ve created before, you again need to run the activate script of that virtual environment.

At this point, you’ve covered the essentials of working with Python virtual environments.

If that’s all you need, then happy trails as you continue creating!

However, if you want to know what exactly just happened,

why so many tutorials ask you to create a virtual environment in the first place,

and what a Python virtual environment really is,

then keep on reading! You’re about to go deep!

Why Do You Need Virtual Environments?

Nearly everyone in the Python community suggests that you use virtual environments for all your projects.

But why?

If you want to find out why you need to set up a Python virtual environment in the first place,

then this is the right section for you.

The short answer is that Python isn’t great at dependency management.

If you’re not specific,

then pip will place all the external packages that you install in a folder called site-packages/ in your base Python installation.

Technically, Python comes with two site-packages folders:

purelib/should contain only modules written in pure Python code.platlib/should contain binaries that aren’t written in pure Python, for example.dll,.so, or.pydistfiles.

You can find these folders in different locations if you’re working on Fedora or RedHat Linux distributions.

However, most operating systems implement Python’s site-packages setting so that both locations point to the same path, effectively creating a single site-packages folder.

You can check the paths using sysconfig:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

>>>

>>> import sysconfig

>>> sysconfig.get_path("purelib")

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310\Lib\site-packages'

>>> sysconfig.get_path("platlib")

'C:\Users\Name\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310\Lib\site-packages'

>>>

>>> import sysconfig

>>> sysconfig.get_path("purelib")

'/home/name/path/to/venv/lib/python3.10/site-packages'

>>> sysconfig.get_path("platlib")

'/home/name/path/to/venv/lib/python3.10/site-packages'

>>>

>>> import sysconfig

>>> sysconfig.get_path("purelib")

'/Users/name/path/to/venv/lib/python3.10/site-packages'

>>> sysconfig.get_path("platlib")

'/Users/name/path/to/venv/lib/python3.10/site-packages'

Most likely, both outputs will show you the same path. If both outputs are the same, then your operating system doesn’t put purelib modules into a different folder than platlib modules. If two different paths show up, then your operating system makes this distinction.

Even if your operating system distinguishes between the two, dependency conflicts will still arise because all purelib modules will go into a single location for purelib modules, and the same will happen with the platlib modules.

To work with virtual environments, you don’t need to worry about the implementation detail of a single site-packages folder or two separate ones. In fact, you probably won’t ever need to think about it again. If you want to, however, you can keep in mind that when someone mentions Python’s site-packages directory, they could be talking about two different directories.

Several issues can come up if all of your external packages land in the same folder. In this section, you’ll learn more about them, as well as other problems that virtual environments mitigate.

Avoid System Pollution

Linux and macOS come preinstalled with a version of Python that the operating system uses for internal tasks.

If you install packages to your operating system’s global Python, these packages will mix with the system-relevant packages. This mix-up could have unexpected side effects on tasks crucial to your operating system’s normal behavior.

Additionally, if you update your operating system, then the packages you installed might get overwritten and lost. You don’t want either of those headaches to happen!

Sidestep Dependency Conflicts

One of your projects might require a different version of an external library than another one. If you have only one place to install packages, then you can’t work with two different versions of the same library. This is one of the most common reasons for the recommendation to use a Python virtual environment.

To better understand why this is so important, imagine you’re building Django websites for two different clients. One client is comfortable with their existing web app, which you initially built using Django 2.2.26, and that client refuses to update their project to a modern Django version. Another client wants you to include async functionality in their website, which is only available starting from Django 4.0.

If you installed Django globally, you could only have one of the two versions installed:

- Windows

- Linux + macOS

PS> python -m pip install django==2.2.26

PS> python -m pip list

Package Version

---------- -------

Django 2.2.26

pip 22.0.4

pytz 2022.1

setuptools 58.1.0

sqlparse 0.4.2

PS> python -m pip install django==4.0.3

PS> python -m pip list

Package Version

---------- -------

asgiref 3.5.0

Django 4.0.3

pip 22.0.4

pytz 2022.1

setuptools 58.1.0

sqlparse 0.4.2

tzdata 2022.1

$ python3 -m pip install django==2.2.26

$ python3 -m pip list

Package Version

---------- -------

Django 2.2.26

pip 22.0.4

pytz 2022.1

setuptools 58.1.0

sqlparse 0.4.2

$ python3 -m pip install django==4.0.3

$ python3 -m pip list

Package Version

---------- -------

asgiref 3.5.0

Django 4.0.3

pip 22.0.4

pytz 2022.1

setuptools 58.1.0

sqlparse 0.4.2

If you install two different versions of the same package into your global Python environment, the second installation overwrites the first one. For the same reason, having a single virtual environment for both clients won’t work either. You can’t have two different versions of the same package in a single Python environment.

Looks like you won’t be able to work on one of the two projects with this setup! However, if you create a virtual environment for each of your clients’ projects, then you can install a different version of Django into each of them:

- Windows

- Linux + macOS

PS> mkdir client-old

PS> cd client-old

PS> python -m venv venv --prompt="client-old"

PS> venvScriptsactivate

(client-old) PS> python -m pip install django==2.2.26

(client-old) PS> python -m pip list

Package Version

---------- -------

Django 2.2.26

pip 22.0.4

pytz 2022.1

setuptools 58.1.0

sqlparse 0.4.2

(client-old) PS> deactivate

PS> cd ..

PS> mkdir client-new

PS> cd client-new

PS> python -m venv venv --prompt="client-new"

PS> venvScriptsactivate

(client-new) PS> python -m pip install django==4.0.3

(client-new) PS> python -m pip list

Package Version

---------- -------

asgiref 3.5.0

Django 4.0.3

pip 22.0.4

setuptools 58.1.0

sqlparse 0.4.2

tzdata 2022.1

(client-new) PS> deactivate

$ mkdir client-old

$ cd client-old

$ python3 -m venv venv --prompt="client-old"

$ source venv/bin/activate

(client-old) $ python -m pip install django==2.2.26

(client-old) $ python -m pip list

Package Version

---------- -------

Django 2.2.26

pip 22.0.4

pytz 2022.1

setuptools 58.1.0

sqlparse 0.4.2

(client-old) $ deactivate

$ cd ..

$ mkdir client-new

$ cd client-new

$ python3 -m venv venv --prompt="client-new"

$ source venv/bin/activate

(client-new) $ python -m pip install django==4.0.3

(client-new) $ python -m pip list

Package Version

---------- -------

asgiref 3.5.0

Django 4.0.3

pip 22.0.4

setuptools 58.1.0

sqlparse 0.4.2

(client-new) $ deactivate

If you now activate either of the two virtual environments, then you’ll notice that it still holds its own specific version of Django. The two environments also have different dependencies, and each only contains the dependencies necessary for that version of Django.

With this setup, you can activate one environment when you work on one project and another when you work on another. Now you can keep any number of clients happy at the same time!

Minimize Reproducibility Issues

If all your packages live in one location, then it’ll be difficult to only pin dependencies that are relevant for a single project.

If you’ve worked with Python for a while, then your global Python environment might already include all sorts of third-party packages. If that’s not the case, then pat yourself on the back! You’ve probably installed a new version of Python recently, or you already know how to handle virtual environments to avoid system pollution.

To clarify what reproducibility issues you can encounter when sharing a Python environment across multiple projects, you’ll look into an example situation next. Imagine you’ve worked on two independent projects over the past month:

- A web scraping project with Beautiful Soup

- A Flask application

Unaware of virtual environments, you installed all necessary packages into your global Python environment:

- Windows

- Linux + macOS

PS> python -m pip install beautifulsoup4 requests

PS> python -m pip install flask

$ python3 -m pip install beautifulsoup4 requests

$ python3 -m pip install flask

Your Flask app has turned out to be quite helpful, so other developers want to work on it as well. They need to reproduce the environment that you used for working on it. You want to go ahead and pin your dependencies so that you can share your project online:

- Windows

- Linux + macOS

PS> python -m pip freeze

beautifulsoup4==4.10.0

certifi==2021.10.8

charset-normalizer==2.0.12

click==8.0.4

colorama==0.4.4

Flask==2.0.3

idna==3.3

itsdangerous==2.1.1

Jinja2==3.0.3

MarkupSafe==2.1.1

requests==2.27.1

soupsieve==2.3.1

urllib3==1.26.9

Werkzeug==2.0.3

$ python3 -m pip freeze

beautifulsoup4==4.10.0

certifi==2021.10.8

charset-normalizer==2.0.12

click==8.0.4

Flask==2.0.3

idna==3.3

itsdangerous==2.1.1

Jinja2==3.0.3

MarkupSafe==2.1.1

requests==2.27.1

soupsieve==2.3.1

urllib3==1.26.9

Werkzeug==2.0.3

Which of these packages are relevant for your Flask app, and which ones are here because of your web scraping project? It’s hard to tell when all external dependencies live in a single bucket.

With a single environment like this one, you’d have to manually go through the dependencies and know which are necessary for your project and which aren’t. At best, this approach is tedious, but more likely, it’s error prone.

If you use a separate virtual environment for each of your projects, then it’ll be more straightforward to read the project requirements from your pinned dependencies. That means you can share your success when you develop a great app, making it possible for others to collaborate with you!

Dodge Installation Privilege Lockouts

Finally, you may need administrator privileges on a computer to install packages into the host Python’s site-packages directory. In a corporate work environment, you most likely won’t have that level of access to the machine that you’re working on.

If you use virtual environments, then you create a new installation location within the scope of your user privileges, which allows you to install and work with external packages.

Whether you’re coding as a hobby on your own machine, developing websites for clients, or working in a corporate environment, using a virtual environment will save you lots of grief in the long run.

What Is a Python Virtual Environment?

At this point, you’re convinced that you want to work with virtual environments.

Great, but what are you working with when you use a virtual environment?