A mouse button is an electric switch on a computer mouse which can be pressed (“clicked”) to select or interact with an element of a graphical user interface. Mouse buttons are most commonly implemented as miniature snap-action switches (micro switches).

Five-button ergonomic mouse

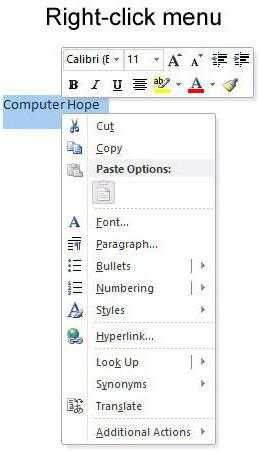

The three-button scrollmouse has become the most commonly available design. Users most commonly employ the second button to invoke a contextual menu in the computer’s software user interface, which contains options specifically tailored to the interface element over which the pointer currently sits. By default, the primary mouse button sits located on the left-hand side of the mouse, for the benefit of right-handed users; left-handed users can usually reverse this configuration via software.

DesignEdit

In contrast to its motion-tracking mechanism, the mouse’s buttons have changed little over the years, varying mostly in shape, number, and placement.

A mouse click is the action of pressing (i.e. ‘clicking’, an onomatopoeia) a button to trigger an action, usually in the context of a graphical user interface (GUI). “Clicking” an onscreen button is accomplished by pressing on the real mouse button while the pointer is placed over the onscreen button’s icon.

The reason for the clicking noise made is due to the specific switch technology used nearly universally in computer mice. The switch is a subminiature precision snap-action type; the first of such types were the Honeywell MICRO SWITCH products.

OperationEdit

Double clicking refers to clicking and releasing a button (often the primary one, usually the left button) twice. Software recognizes both clicks, and if the second occurs within a short time, the action is recognised as a double click.

If the second click is made after the time expires it is considered to be a new, single click. Most modern operating systems and mice drivers allow a user to change the speed of a double click, along with an easy way to test the setting. Some software recognises three or more clicks, such as progressively selecting a word, sentence, or paragraph in a word processor text page as more clicks are given in a sequence.

With less abstracted software, a mouse button’s current state (“mouse up” and “mouse down”) is monitored, allowing for modal operations such as drag and drop.

Number of buttonsEdit

Douglas Engelbart’s first mouse had a single button; Xerox PARC soon designed a three-button model, but reduced the count to two for Xerox products. Apple decided on one button for their GUI environments on commercial release in 1983, while most other PC environments standardized on two, and most professional workstation environments used three. Aside from such OEM bundled mice, usually having between one and three buttons, many aftermarket mice have always had five or more, with varying amounts of additional software included to support them.

This state of affairs continued until the late 1990s, when growing support for mice with a scroll wheel after the 1996 introduction of Microsoft’s IntelliMouse incidentally made 3-button pointing devices ubiquitous on OEM hardware. The one major holdout, Apple, finally went multi-button in 2005 with their Mighty Mouse, though all Apple laptops would continue to use one-button trackpads until their first buttonless trackpad in 2008.

ComputerEdit

«My friend Marvin Minsky tells me there’s great controversy in the artificial intelligence community over how many buttons a mouse should have», Jerry Pournelle wrote in 1983.[1] In the matter of the number of buttons, Engelbart favored the view “as many as possible.” The prototype that popularized the idea of three buttons as standard had that number only because “we could not find anywhere to fit any more switches.”

Those favoring single-button mice argue that a single button is simpler for novice users to understand, and for developers to support. In addition, as a lowest common denominator option, it offers both a path gradual advancement in user sophistication for unfamiliar applications, and a fallback for diverse or malfunctioning hardware. Those favoring multiple-button mice argue that support for a single-button mouse often requires clumsy workarounds in interfaces where a given object may have more than one appropriate action. Several common workarounds exist, and some are specified by the Apple Human Interface Guidelines.

One workaround was the double click, first used on the Lisa, to allow both the “select” and “open” operation to be performed with a single button.

Another workaround has the user hold down one or more keys on the keyboard before pressing the mouse button (typically control on a Macintosh for contextual menus). This has the disadvantage that it requires that both the user’s hands be engaged. It also requires that the user perform actions on completely separate devices in concert; that is, holding a key on the keyboard while pressing a button on the mouse. This can be a difficult task for a disabled user, although can be remedied by allowing keys to stick so that they do not need to be held down.

Another involves the press-and-hold technique. In a press-and-hold, the user presses and holds the single button. After a certain period, software perceives the button press not as a single click but as a separate action. This has two drawbacks: first, a slow user may press-and-hold inadvertently. Second, the user must wait for the software to detect the click as a press-and-hold, otherwise the system might interpret the button-depression as a single click. Furthermore, the remedies for these two drawbacks conflict with each other: the longer the lag time, the more the user must wait; and the shorter the lag time, the more likely it becomes that some user will accidentally press-and-hold when meaning to click. Studies have found all of the above workarounds less usable than additional mouse buttons for experienced users.[citation needed]

A workaround for users of two-button mice in environments designed for three buttons is mouse chording, to simulate a tertiary-click by pressing both buttons simultaneously.[2]

Additional buttonsEdit

Aftermarket manufacturers have long built mice with five or more buttons. Depending on the user’s preferences and software environment, the extra buttons may allow forward and backward web-navigation, scrolling through a browser’s history, or other functions, including mouse related functions like quick-changing the mouse’s resolution/sensitivity. As with similar features in keyboards, however, not all software supports these functions. The additional buttons become especially useful in computer gaming, where quick and easy access to a wide variety of functions (such as macros and DPI changes) can give a player an advantage. Because software can map mouse-buttons to virtually any function, keystroke, application or switch, extra buttons can make working with such a mouse more efficient and easier.

Scroll wheelEdit

Scrollmice almost always mount their scroll wheels on an internal spring-loaded frame and switch, so that simply pushing down makes them work as an extra button, made easier to do without accidentally spinning it by wheel detents present in most scrollmice. The wheel can both be rotated and clicked, thus most mice today effectively have three buttons.

In web browsers, clicking on a hyperlink opens it in a new tab, and clicking on a tab itself usually closes it.

Some mice have scroll wheels that can be tilted sideways for sideways scrolling.

Omnidirectional scrolling can be performed in various document viewers including web browsers and PDF readers by middle-clicking and moving the pointer in any direction. This can be done by holding and scrolling until released, or by short clicking and scrolling until clicking once more (any mouse button) or pressing the Esc key.[3] Some applications such as «Xreader» simulate a drag-to-scroll gesture as used by touch screen devices such as smartphones and tablet computers.[4]

In Linux, pressing the left and right mouse buttons simultaneously simulates a middle click, and middle-clicking into a text area pastes the clipboard at the mouse cursor’s location (not the blinking cursor’s existing location).[5]

Text editors including Kate and Xed allow switching between open tabs by scrolling while the cursor points at the tab bar.

Software environment useEdit

The Macintosh user interface, by design, always has and still does make all functions available with a single-button mouse. Apple’s Human Interface Guidelines still specify that other developers need to make all functions available with a single-button mouse as well. Various functions commonly done with additional buttons on other platforms were, when implemented on the Mac by most developers, instead done in conjunction with modifier keys. For instance, contextual menus were most often invoked by “Control Key-click,” a behavior later explicitly adopted by Apple in OS 8’s Contextual Menu Manager.

While there has always been a Macintosh aftermarket for mice and other pointing devices with two, three, or more buttons, and extensive configurable support (usually through keyboard emulation) to complement such devices in many major software packages on the platform, it wasn’t until Mac OS X shipped that support for multi-button mice was hardcoded. X Window System applications, which Mac OS X can also run, have been developed with the use of two or three-button mice in mind.

While historically, most PC mice provided two buttons, only the primary button was standardized in use for MS-DOS and versions of Windows through 3.1x; support and functionality for additional buttons was application specific. However, in 1992, Borland released Quattro Pro for Windows (QPW), which used the right (or secondary) mouse button to bring up a context menu for the screen object clicked (an innovation previously used on the Xerox Alto, but new to most users). Borland actively promoted the feature, advertising QPW as “The right choice,” and the innovation was widely hailed as intuitive and simple. Other applications quickly followed suit, and the “right-click for properties” gesture was cemented as standard Windows UI behavior after it was implemented throughout Windows 95.

Most machines running Unix or a Unix-like operating system run the X Window System which almost always encourages a three-button mouse. X numbers the buttons by convention. This allows user instructions to apply to mice or pointing devices that do not use conventional button placement. For example, a left-handed user may reverse the buttons, usually with a software setting. With non-conventional button placement, user directions that say “left mouse button” or “right mouse button” are confusing. The ground-breaking Xerox Parc Alto and Dorado computers from the mid-1970s used three-button mice, and each button was assigned a color. Red was used for the left (or primary) button, yellow for the middle (secondary), and blue for the right (meta or tertiary). This naming convention lives on in some Smalltalk environments, such as Squeak, and can be less confusing than the right, middle and left designations.

Acorn’s RISC OS based computers necessarily use all three mouse buttons throughout their WIMP based GUI. RISC OS refers to the three buttons (from left to right) as Select, Menu and Adjust. Select functions in the same way as the “Primary” mouse button in other operating systems. Menu will bring up a context-sensitive menu appropriate for the position of the pointer, and this often provides the only means of activating this menu. This menu in most applications equates to the “Application Menu” found at the top of the screen in Mac OS, and underneath the window title under Microsoft Windows. Adjust serves for selecting multiple items in the “Filer” desktop, and for altering parameters of objects within applications – although its exact function usually depends on the programmer.

ReferencesEdit

- ^ Pournelle, Jerry (June 1983). «Zenith Z-100, Epson QX-10, Software Licensing, and the Software Piracy Problem». BYTE. Vol. 8, no. 6. p. 411. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Garfinkel, Simson L. (November–December 1988). «A Second Wind for Athena» (PDF). Technology Review. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ The Many Things You Can Do with a Middle Click on Your Mouse – April 22, 2014 – LifeHacker

- ^ «Linuxmint/Xreader». GitHub. 7 May 2022.

- ^ «The Linux GUI: Of mice and menus». 3 August 2004.

Mice and Joysticks

A mouse is the primary input device for modern computers that feature operating systems

with a graphical user interface, such as Windows 3.11 or Windows 95. While keyboards

obviously excel at entering text, numbers, and symbols, your mouse is the tool you’ll use

to tell your computer what to do with all the data you’ve entered.

Joysticks are almost exclusively used with game software and help the

user more effectively control the actions of computer-simulated airplanes or arcade-style

games.

Defining Mice

All modern PC operating systems (Windows 3.11, Windows 95, and the

Macintosh) rely on an on-screen pointer to select and execute commands. A mouse is simply

an input device built to help the user control this on-screen pointer in as natural and

efficient a manner as possible.

The pointer on the screen mimics the movements of your mouse. As you

move your mouse, a ball encased in the bottom of your mouse rolls on the desk and in turn

sends signals to the computer as to which direction to move the pointer on the screen.

Move the mouse side to side, or up and down, and the on-screen pointer moves in a similar

manner.

Once you have the mouse positioned to select the command or data you

want to act on, you use the mouse buttons to execute the command.The mouse controls the

on-screen pointer and lets you select program icons, manipulate property sheets, and

access data.

Connecting a Mouse

Your mouse connects to your PC either through a dedicated mouse port or

a standard 9-pin serial port. Once you’re familiar with what the mouse connectors look

like you can go ahead and connect your mouse using the following steps:

- 1. Save any open documents, and then close all active applications.

2. Identify which type of mouse connector you have and its corresponding connector

on the back of your computer.3. Carefully position the connector so that it matches the connector on the back of

your PC, and gently press it into place.4. In most cases, you’ll have to restart your computer in order for the operating

system to recognize your mouse.

NOTE: For computers running Windows 3.11, the process is a little

more involved and requires installing MS-DOS mouse drivers (mouse.com and mouse.sys in

most cases). If you have Windows 3.11, you’ll need to refer to the manual that came with

your mouse for complete installation instructions.

Using the Mouse Buttons

Most mice have two buttons. In Windows 95, the left button selects text

and data, executes commands, and manipulates data, while the right mouse button accesses

context menus.

Pressing a mouse button and then releasing it is known as clicking

your mouse. You can click both left and right mouse buttons. Pressing the button and

releasing it twice in quick succession is called double-clicking.

The Left Mouse Button

It seems simple, but there are a lot of things you can do by combining

various types of mouse clicks with mouse movements. Table 13.1 gives you some examples.

Table 13.1 Left Mouse Button Operations

|

Task |

Mouse Button |

| Select items |

Press and hold down the left mouse button. Move the mouse to select desired text, numbers, or objects. Release mouse button. The selected text is highlighted. |

|

Move selected items (also called click and drag) |

Position mouse over highlighted text. Press and hold left mouse button down. While holding down left mouse button, move mouse (and the selected items) to their new location and release mouse button. |

| Access a menu or command |

Position pointer over menu or property box button; press and release left mouse button quickly. |

| Start a program |

Quickly press and release the left mouse button twice (double-click). |

NOTE: Windows 95 lets you customize what each of the buttons does

through the Mouse Properties dialog box. This can be a help if you have a three-button

mouse. See the section «Adjusting Mouse Properties» later in the chapter for

examples.

The Right Mouse Button

The right mouse button is generally reserved for special uses. In

Windows 95, the right mouse button accesses a context menu that lists the available

options for the item you’ve just clicked.

The right mouse button does different things, depending on which type

of item you click. See below table for some examples.

Right Mouse Button Operations

|

Action |

Menu Options |

| Right-clicking a file |

This pulls up a menu that asks you if you want to open, print, delete, or send the file somewhere. |

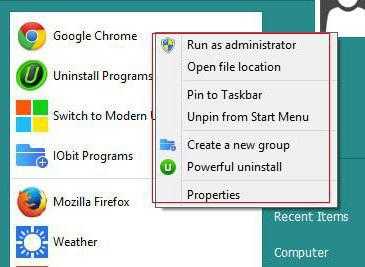

| Right-clicking a program |

Presents you with a menu that lets you open, create a shortcut, or access that program’s property sheet. |

|

Click and drag a file (press and hold the mouse key while moving it) |

Presents you with a menu that lets you choose to move or copy the file to its new location. |

Using the IntelliMouse Wheel

Microsoft’s newest mouse features a small wheel in between the two

mouse buttons. The wheel directly controls an application’s scroll bar (see Chapter 6,

«Working with Applications») letting you move up and down in a document without

having to move the pointer off to the right of the screen. You can also use the

IntelliMouse to pan in documents by clicking the wheel and moving the mouse in the

direction you’d like to pan. When you’re ready to stop panning, click the wheel again.

Three-Button Mice

Some mice have three buttons. Usually the mouse comes with software

that lets you customize what that third button does. Windows 95 also supports many of the

more popular three-button mice and may have built-in support for that third button. If you

have a three-button mouse, see the following section for tips on how to use the third

button.

Adjusting Mouse Properties

Windows 95 allows you to customize your mouse to best suit your style.

You can adjust the speed at which the mouse moves the pointer across the screen, the

amount of time allowed between the clicks of a double-click, and how the pointer appears

on the screen. Left-handed computer users can configure the mouse to work best with the

left hand.

These adjustments are made through the Mouse Properties dialog box. The

Mouse Properties program is in Windows 95’s Control Panel. You can get to it by clicking

Start, Settings, Control Panel. You should then see the Mouse icon. Double-click the Mouse

icon to start the Mouse Properties program.

Configuring Mouse Double-Click Speed

To configure mouse speed when double-clicking:

- 1. Click Start, Settings, Control Panel and then double-click the Mouse icon.

2. Click the Buttons tab.

3. To adjust the amount of time needed between double-clicks, slide the bar in the

bottom half of the Buttons tab of the Mouse Properties dialog box either left or right.

(Hold the left mouse button down while moving the mouse, then release after you’ve moved

the slider.)4. You can test your setting by double-clicking the jack-in-the-box—if he pops up,

you’ve clicked fast enough (see Figure 13.3).

Configuring Right- or Left-Hand Mouse Preferences

To change your mouse for right or left-handers:

- 1. Click Start, Settings, Control Panel and then double-click the Mouse icon.

2. To switch between right- and left-handed mouse configurations, click either the

Right-handed

or Left-handed option buttons in the top of the Buttons tab of the Mouse Properties

dialog box (see Figure 13.3).

Adjusting Pointer Speed

You can control how fast the pointer moves on the screen in relation to

your mouse movements on your desk. You can have the pointer move completely from one side

of the screen to the other with only the slightest mouse movement, or you can slow the

pointer down for greater control.

The pointer speed is set in the same Mouse Properties dialog box as

mentioned earlier:

- 1. Click Start, Settings, Control Panel, then double-click the Mouse icon.

2. Once the dialog box is open, click the Motion tab

Cleaning a Mouse

If your pointer starts moving erratically, or your mouse isn’t moving

smoothly, it’s probably time to clean your mouse. This is a simple process:

- 1. Carefully remove the mouse ball. On the bottom of your mouse there will be a

cover plate that usually just twists off. If you have trouble getting the cover off, refer

to your mouse manual.2. Once the ball is out, roll it between your fingers to remove any dirt.

3. Inspect the inside of the mouse and carefully remove any dirt you find in there,

especially any dirt that has collected on the little rollers that come in contact with the

mouse ball.4. Reassemble your mouse and give it try.

A thorough cleaning usually does the trick. If no amount of cleaning

helps, you may be in need of a new mouse.

Defining Joysticks

Joysticks are basically sticks attached to a base unit that measures

the distance the stick is moved left, right, up, down, or diagonally. Electronic sensors

in the base unit translate those motions into motions that are understood by the computer

and software.

Joysticks are almost exclusively used with game software; they are not

designed to replace a mouse.

Types of Joysticks

Joysticks come in various shapes and sizes. Some are built to mimic the

flight controls of an airplane, complete with buttons to fire guns and missiles. Others

aren’t sticks at all, but may be steering wheels designed to help the user more

effectively play driving simulation games. In general, computer input devices used to help

users play computer games are called joysticks.

Connecting a Joystick

Joysticks all connect with a 15-pin D-shaped connector. See Figure 13.5

for an example of a joystick connector.

Connecting a joystick is simple. To connect yours, follow these steps:

- 1. Save any open documents, and then close all active applications.

2. Identify the joystick connector on the back of your computer.

3. Carefully position the connector so that it matches the connector on the back of

your PC, and gently press it into place.4. In most cases, you’ll have to restart your computer in order for the operating

system to recognize your joystick.

If the computer doesn’t initially see your joystick, you’ll need to run

Windows 95’s Add Hardware Wizard. You can access the Add Hardware Wizard by clicking

Start, Settings, Control Panel. The Add Hardware Wizard will be one of the icons in the

Control Panel folder.

Calibrating Your Joystick

Calibrating your joystick lets you «center» your joystick so

that when released it returns to a neutral position. It also makes certain that movements

from side to side, or front to back result in smooth and predictable movement on the

screen.

There are two ways to calibrate your joystick. One is through the

Joystick Properties dialog box, and the other is through calibration sliders on the

joystick itself.

Calibrating Your Joystick with Software

To calibrate your joystick through the Joystick Properties dialog click

Start, Settings, Control Panel and double-click the Joystick icon. There, you’ll see

sliders that let you set the default X and Y axis positions of the joystick. You calibrate

your mouse by adjusting these sliders.

Calibrating Your Joystick with Hardware

You can also calibrate most joysticks via slider bars, or wheels, that

are on the joystick itself. Inspect your joystick to see if it has built-in calibration

adjusters.

One button mouse

Three-button mouse

Five button ergonomic mouse

A mouse button is a microswitch on a computer mouse which can be pressed («clicked») in order to select or interact with an element of a graphical user interface.

The three-button scrollmouse has become the most commonly available design. As of 2007 (and roughly since the late 1990s), users most commonly employ the second button to invoke a contextual menu in the computer’s software user interface, which contains options specifically tailored to the interface element over which the mouse cursor currently sits. By default, the primary mouse button sits located on the left-hand side of the mouse, for the benefit of right-handed users; left-handed users can usually reverse this configuration via software.

Contents

- 1 Design

- 2 Operation

- 3 Number of buttons

- 4 Additional buttons

- 5 Scroll wheel

- 6 Operating system use

- 7 References

Design

In contrast to the motion-sensing mechanism, the mouse’s buttons have changed little over the years, varying mostly in shape, number, and placement. Engelbart’s very first mouse had a single button; Xerox PARC soon designed a three-button model, but reduced the count to two for Xerox products. After experimenting with 4-button prototypes Apple reduced it back to one button with the Macintosh in 1984, while Unix workstations from Sun and others used three buttons. OEM bundled mice usually have between one and three buttons, although in the aftermarket many mice have always had five or more.

A mouse click is the action of pressing (i.e. ‘clicking’, an onomatopoeia) a button in order to trigger an action, usually in the context of a graphical user interface (GUI). ‘Clicking’ an onscreen button is accomplished by pressing on the real mouse button while the cursor is placed over the button icon.

The reason for the clicking noise made is due to the specific switch technology used nearly universally in computer mice. The switch is a subminiature precision snap-action type; the first of such types were the Honeywell MICRO SWITCH™ products. (See micro switch.)

Operation

Double clicking refers to clicking (and, naturally, releasing) a button (often the primary one) twice. Software recognizes both clicks, and if the second occurs within a short time, the action is recognized as a double click.

If the second click is made after the time expires it is considered to be a new, single click. Most modern operating systems and mice drivers allow a user to change the speed of a double click, along with an easy way to test the setting. Some software recognize three or more clicks, such as progressively selecting a word, sentence, or paragraph in a word processor text page as more clicks are given in a sequence.

Number of buttons

From the first Macintosh until late 2005 Apple shipped every computer with a single-button mouse, whereas most other platforms used multi-button mice. Apple and its advocates promoted single-button mice as more user-friendly, and portrayed multi-button mice as confusing for novice users and that multiple button mice interfaces introduce computer accessibility restrictive elements[dead link] including right click, double click, and middle click.

On August 2, 2005, Apple introduced their Mighty Mouse multi-button mouse, which has four independently-programmable buttons and a trackball-like «scroll ball» which allows the user to scroll in any direction. Since the mouse uses touch-sensitive technology, users can treat it as a one-, two-, three-, or four-button mouse, as desired.

More recently, Apple has released a mouse with no buttons, but instead the touch sensitivity of the new Multi-Touch trackpads. Left and right click are available in their respective areas, but that space is also used when scrolling, since the mouse is simply one surface on the top. The standard optics of the Mighty Mouse appear on the underside of the new Magic Mouse.

Additional buttons

Aftermarket manufacturers have long built mice with five or more buttons. Depending on the user’s preferences and software environment, the extra buttons may allow forward and backward web-navigation, scrolling through a browser’s history, or other functions, including mouse related functions like quick-changing the mouse’s resolution/sensitivity. As with similar features in keyboards, however, not all software supports these functions. The additional buttons become especially useful in computer gaming, where quick and easy access to a wide variety of functions (such as macros and dpi changes) can give a player an advantage. Because software can map mouse-buttons to virtually any function, keystroke, application or switch, extra buttons can make working with such a mouse more efficient and easier.

In the matter of the number of buttons, Douglas Engelbart favored the view «as many as possible». The prototype that popularized the idea of three buttons as standard had that number only because «we could not find anywhere to fit any more switches».

On systems with three-button mice, pressing the center button (a middle click) typically opens a system-wide noncontextual menu. In the X Window System, middle-clicking by default pastes the contents of the primary buffer at the cursor’s position. Many users of two-button mice emulate a three-button mouse by clicking both the right and left buttons simultaneously.

Common mice have a wheel with a detent («bumpy» feel) to keep it from drifting accidentally; this wheel also has an optical encoder like those for the ball; it’s typically used to scroll a tall window vertically. However, many such scroll wheels are mounted in a little internal spring-loaded frame so that simply pushing down on them makes them work as a third button.

Scroll wheel

Main article: scroll wheel

The scroll wheel, a notably different form of mouse-button, consists of a small wheel that the user can rotate to provide immediate one-dimensional input. Usually, this input translates into «scrolling» up or down within the active window or GUI-element. The wheel is often – but not always – engineered with a detent to turn in short steps, rather than continuously, to allow the operator to more easily intuit how far they are scrolling. The scroll wheel nearly always includes a third (center) button, activated by pushing the wheel down into the mouse.

The scroll wheel can provide convenience, especially when navigating a long document. In conjunction with the control key (Ctrl), the mouse wheel may often be used for zooming in and out; applications that support this feature include Adobe Reader, Microsoft Word, Internet Explorer, Opera, Mozilla Firefox and Mulberry, and in Mac OS X, holding the control key while scrolling zooms in on the entire screen. Some applications also allow the user to scroll left and right by pressing the shift key while using the mouse wheel.

Manufacturers may refer to scroll-wheels by different names for branding purposes; Genius, for example, usually brand their scroll-wheel-equipped products «Netscroll».

Mouse Systems invented the scroll wheel in the early 1990s,[1] marketing it as the Mouse Systems ProAgio and Genius EasyScroll. However, mainstream adoption of the scroll wheel mouse did not occur until Microsoft released the Microsoft IntelliMouse in 1996. It became a commercial success in 1997 when their Microsoft Office application suite and their Internet Explorer browser started supporting its wheel-scrolling feature.[1] Since then the scroll wheel has become a standard feature of many mouse models.

Some mouse models have two wheels, or wheels that can be moved sideways (such as the MX Revolution), separately assigned to horizontal and vertical scrolling. Designs exist which make use of a «rocker» button instead of a wheel – a pivoting button that a user can press at the top or bottom, simulating «up» and «down» respectively. A peculiar early example was a mouse by Saitek which had a joystick-style hatswitch on it.[citation needed]

A more recent form of mouse wheel is the tilt-wheel. Tilt wheels are essentially conventional mouse wheels that have been modified with a pair of sensors articulated to the tilting mechanism. These sensors are mapped, by default, to horizontal scrolling.

A third variety of built-in scrolling device, the scroll ball, essentially consists of a trackball embedded in the upper surface of the mouse. The user can scroll in all possible directions in very much the same way as with the actual mouse, and in some mice, can use it as a trackball. Mice featuring a scroll ball include Apple’s Mighty Mouse and the IOGEAR 4D Web Cruiser Optical Scroll Ball Mouse. IBM’s ergonomics laboratory designed a mouse with a pointing stick in it,[2] envisioned to be used for scrolling, zooming or (with appropriate software) controlling a second mouse cursor.

Some mice, like some models by Genius, have an optical sensor instead of a wheel. This sensor allows to scroll in both horizontal and vertical directions.[3]

Operating system use

The Macintosh user interface, by design, always has and still does make all functions available with a single-button mouse. Apple’s Human Interface Guidelines still specify that all software-providers need to make functions available with a single button mouse. Context menus are available using the Control Key ctrl.

The original Mac OS assumed a one-button mouse. While there has long been an aftermarket for mice with two, three, or more buttons, and extensive configurable support to complement such devices in all major software packages on the platform, Mac OS X shipped with hardcoded support for multi-button mice. X Window System applications, which Mac OS X can also run, have developed with the use of two-button or even three-button mice in mind.

Advocates of multiple-button mice argue that support for a single-button mouse often leads to clumsy workarounds in interfaces where a given object may have more than one appropriate action. One workaround was the double click, first used on the Apple Lisa, to allow both the «select» and «open» operation to be performed with a single button. Several common workarounds exist, and some are specified by the Apple Human Interface Guidelines.

One such workaround (that favored on Apple platforms) has the user hold down one or more keys on the keyboard before pressing the mouse button (typically control on a Macintosh for contextual menus). This has the disadvantage that it requires that both the user’s hands be engaged. It also requires that the user perform actions on completely separate devices in concert; that is, holding a key on the keyboard while pressing a button on the mouse. This can be a difficult task for a disabled user, although can be remedied by allowing keys to stick so that they do not need to be pressed down.

Another involves the press-and-hold technique. In a press-and-hold, the user presses and holds the single button. After a certain period, software perceives the button press not as a single click but as a separate action. This has two drawbacks: first, a slow user may press-and-hold inadvertently. Second, the user must wait for the software to detect the click as a press-and-hold, otherwise the system might interpret the button-depression as a single click. Furthermore, the remedies for these two drawbacks conflict with each other: the longer the lag time, the more the user must wait; and the shorter the lag time, the more likely it becomes that some user will accidentally press-and-hold when meaning to click. Studies have found all of the above workarounds less usable than additional mouse buttons for experienced users.[citation needed]

While historically, most PC mice provided two or three buttons, only the primary button was standardized in use for MS-DOS and versions of Windows through 3.1x; support and functionality for additional buttons was application specific. However, in 1992, Borland released Quattro Pro for Windows (QPW), which used the right (or secondary) mouse button to bring up a context menu for the screen object clicked (an innovation previously used on the Xerox Alto, but new to most users). Borland actively promoted the feature, advertising QPW as «The right choice», and the innovation was widely hailed as intuitive and simple. Other applications quickly followed suit, and the «right-click for properties» gesture was cemented as standard Windows UI behavior after it was implemented throughout Windows 95.

Most machines running Unix or a Unix-like operating system run the X Window System which almost always encourages a three-button mouse. X numbers the buttons by convention. This allows user instructions to apply to mice or pointing devices that do not use conventional button placement. For example, a left-handed user may reverse the buttons, usually with a software setting. With non-conventional button placement, user directions that say «left mouse button» or «right mouse button» are confusing. The ground-breaking Xerox Parc Alto and Dorado computers from the mid-1970s used three-button mice, and each button was assigned a color. Red was used for the left (or primary) button, yellow for the middle (secondary), and blue for the right (meta or tertiary). This naming convention lives on in some Smalltalk environments, such as Squeak, and can be less confusing than the right, middle and left designations.

Acorn’s RISC OS based computers necessarily use all three mouse buttons throughout their WIMP based GUI. RISC OS refers to the three buttons (from left to right) as Select, Menu and Adjust. Select functions in the same way as the «Primary» mouse button in other operating systems. Menu will bring up a context-sensitive menu appropriate for the position of the mouse cursor, and this often provides the only means of activating this menu. This menu in most applications equates to the «Application Menu» found at the top of the screen in Mac OS, and underneath the window title under Microsoft Windows. Adjust serves for selecting multiple items in the «Filer» desktop, and for altering parameters of objects within applications – although its exact function usually depends on the programmer.

References

- ^ a b Joe Kissell (October 7, 2004, updated 2006). «The Evolution of Scrolling: Reinventing the wheel». Interesting Thing of the Day. http://itotd.com/articles/330/the-evolution-of-scrolling/. Retrieved 2010-02-12.

- ^ «TrackPoint Mouse». http://www.almaden.ibm.com/cs/user/tp/tpmouse.html.

- ^ «Navigator 525 Laser Mouse». http://www.geniusnet.com/geniusOnline/online.portal?_nfpb=true&productPortlet_actionOverride=%2Fportlets%2FproductArea%2Fcategory%2FqueryPro&_windowLabel=productPortlet&productPortletproductId=638029&_pageLabel=productPage&test=portlet-action.

| v · d · eBasic computer components | |

|---|---|

| Input devices |

Keyboard · Image scanner · Microphone · Pointing device (Graphics tablet · Joystick · Light pen · Mouse · Touchpad · Touchscreen · Trackball) · Webcam (Softcam) |

| Output devices |

Monitor · Printer · Speakers |

| Removable data storage |

Optical disc drive (CD-RW · DVD+RW) · Floppy disk · Memory card · USB flash drive |

| Computer case |

Central processing unit (CPU) · Hard disk / Solid-state drive · Motherboard · Network interface controller · Power supply · Random-access memory (RAM) · Sound card · Video card |

| Data ports |

Ethernet · Firewire (IEEE 1394) · Parallel port · Serial port · Thunderbolt · Universal Serial Bus (USB) |

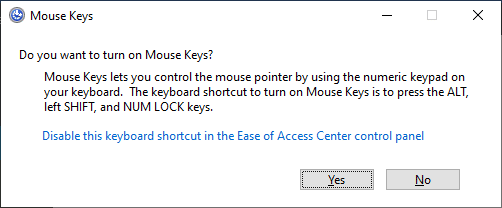

Is it possible to use a Computer Without a Mouse and still accomplish most of the day-to-day tasks using Mouse Keys alone? The day, when you were in hurry and all of a sudden you find out that the Mouse is not working anymore or you might be troubleshooting a Desktop PC without attaching a Mouse in the first place or the Touch-pad of your Notebook/Laptop doesn’t work any more and you have something very urgent to do!

When you need to use a Computer without a Mouse then it is certain that you can’t accomplish all of the tasks using the Keyboard Shortcuts alone. Like, I can’t access all the features of this WordPress Dashboard while writing this blog post using the keyboard shortcuts alone and I’ve to move the Mouse Pointer, need to Left/Right click on certain elements, and Drag-n-Drop objects, which all are not possible through shortcuts alone.

I’m using Mouse Keys since Windows 97 and in my personal experience, you can’t always access and use all the Buttons/Commands of Windows, other Applications or dialog/pop-up boxes using the Keyboard Shortcuts alone.

A combination of both the Mouse Keys and Keyboard Shortcut can make you a Master of Using Computer Without Mouse!

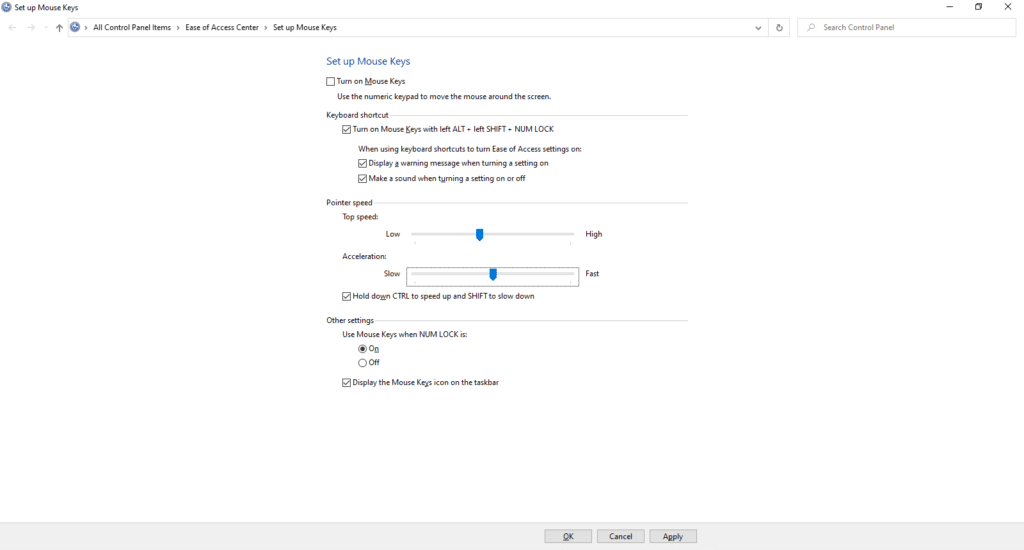

Understanding and Configuring Mouse Keys Settings

- First thing first, the best way to Turn On/Off Mouse Key is to use Left ALT + Left SHIFT + Num Lock keyboard shortcut, which will bring the following pop-up window asking “Do you want to turn on Mouse Keys?” or you can also press the Start key from your keyboard and type Mouse Keys in the Search box. See Figure 1.1:

Basically, you have 3 different choices in the Mouse Keys pop-up box: Yes, No or Disable this keyboard shortcut in the Ease of Access Center Control Panel.

- So, if you simply press “Yes” then that will Turn On the Mouse Key with the Default Settings but I don’t think that what you want as the default Mouse Key settings are not up to the mark and you will definitely like to buy a Mouse instead of using Mouse Keys. The reason behind is the default low rate of Pointer Speed and Acceleration when moved through Mouse Keys.

In Figure 1.1, you will find that default selected button is Yes and hitting the Enter or Space key will immediately Turn On the Mouse Keys feature with the Default Settings.

So, Left SHIFT+Left ALT+Num Lock and hitting Enter Key is the shortest way to Turn On Mouse Keys.

- But wait, I will advise you not to enable the Mouse Key by hitting Yes in the above dialog box instead use the Tab key to change the choice and press Space key on “Disable this keyboard shortcut in the Ease of Access Center control panel.” That will bring the Set up Mouse Keys settings dialog box. See Figure 1.2:

You should configure the options first before turning on the Mouse Keys and here are some Best Mouse Key Settings for you! Watch the following short-video to know how to enable/disable Mouse Keys options using the keyboard alone.

- Pointer Speed : Notice the default Pointer Speed and Acceleration in Figure 1.2, which is set to Medium.You can use the Left and Right arrow keys to increase or decrease the Pointer Speed or Acceleration. My advise is to set them to High and Fast and also Enable “Hold down CTRL to Speed up and SHIFT to slow down” the Mouse Pointer Speed option. We will describe these features in the next section, when we will be using this computer without a mouse.

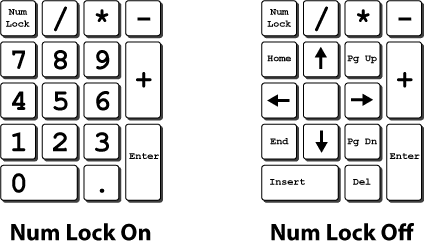

- The NUM LOCK Settings are the most important when you need to use all the keys from the NUM PAD to Move the Mouse Pointer, Select the objects, Drag-n-drop objects etc. You can accomplish all the tasks through Mouse Keys that you do with a Computer Mouse, except for Computer Designing.

- Make sure to set the “Use Mouse Keys when NUM LOCK is:” option to “Off”. That way, when the NUM LOCK will OFF then you will be able to use the NUM PAD as Mouse Keys and when the NUM PAD will ON then you will be able to type all the Numerical Numbers and Symbols through NUM PAD.

If you will set “Use Mouse Keys when NUM LOCK is to ON” then you will not be able to type numerical keys with NUM PAD as they now will be used for Mouse Key movements and other actions.

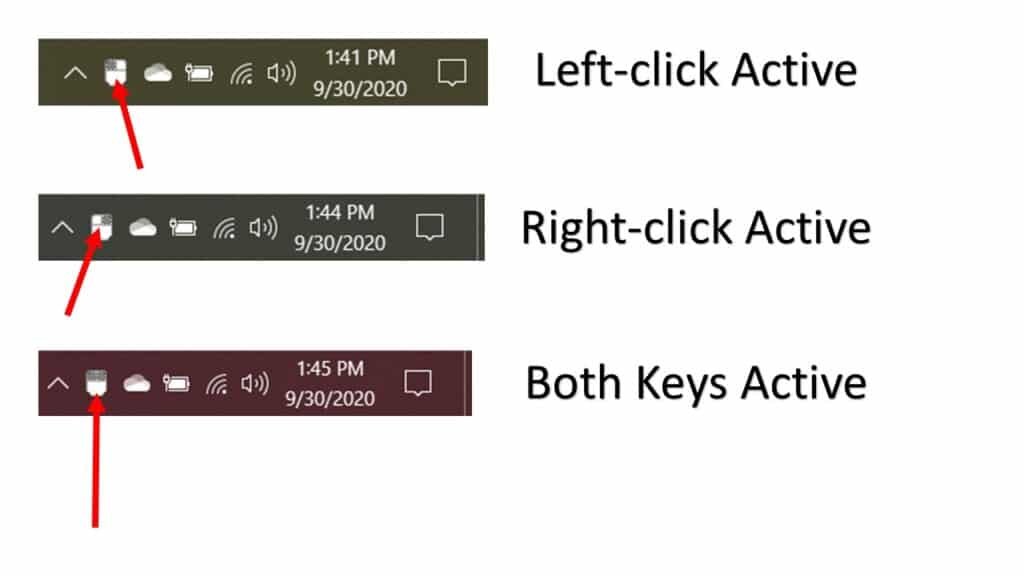

- “Display the Mouse Keys icon on the taskbar” option will disable an icon of Mouse Keys in the System Tray of your Taskbar. It will also display a Cross-Indicator according the status of Num Lock.

- You can also find an option stating “Use Mouse Keys when NUM LOCK is On / Off“. You can move between these options using the TAB Key and can use the SPACE BAR to Enable/Disable or change the options.

- If the Mouse Keys keyboard shortcut key (Left ALT + Left SHIFT + NUM Lock) is clashing with a shortcut from any other application on your system or you don’t want to Turn On Mouse Keys using shortcut at all then you can disable the “Turn on Mouse Keys with left ALT + left SHIFT + NUM LOCK” option under “Keyboard shortcut” section.

Keep in mind, disabling this shortcut will not let you turn on / off the Mouse Keys using shortcut the next time and you have to move to the Control Panel – Ease of Access Center to access the settings or use the Start Search.

- Under “Keyboard shortcut” there are 2 more settings. First one is already shown in Figure 1.1, where Windows “Display a warning message when turning a setting on” when you use Keyboard Shortcut to turn on/off the Mouse Key.

- You also hear certain sounds while using Mouse Keys and turning On/Off certain settings or while pressing keys from the Num Pad and that is what “Make a sound when turning a setting on or off” option is for. If you want to hear the sounds or not. Turning ON the Sounds and displaying the Mouse Keys Icon in the Taskbar will be good ideas! So, Turn On the Mouse Keys and now let’s see:

Understanding NUM PAD Key Roles

First you need to understand that how the Numerical Keys has been distributed to the NUM PAD when Mouse Key is enabled. As we know that we have: 0 to 9 numerical keys and a DOT (.), and all these keys are double-keys playing 2 functions according to the Numerical Lock status.

0 represents INS key, DOT (.) represents Delete Key, 1 as End Key, 2 for Down Arrow, 3 for Page Down, 4 Left Arrow, 5 alone, 6 Right Arrow, 7 as Home Key, 8 for Up movement, and 9 for Page Up.

Now, if you set “Use Mouse Keys when Num Lock is set to Off” then the Num Pad Keys will have the following roles:

- 1 to Move Mouse Pointer Diagonally Bottom Left

- 2 to Move Mouse Pointer Down

- 3 to Move Mouse Pointer Diagonally Bottom Right

- 4 to Move Pointer Left

- 5 to Click (for both Left and Right Click, Depending on Active Mouse Button)

- 6 to Move Pointer Right

- 7 to Move Pointer Diagonally Top Left

- 8 to Move Pointer Up

- 9 to Move Pointer Diagonally Top Right

- Beside that, 0 Key can be used to Drag an item and . Key to Drop an item.

Understanding Active Mouse Button and How To Right-click using Mouse Keys?

When you Turn On Mouse Keys and “Display the Mouse Keys icon on the taskbar” option is checked then you will see an icon in the System Tray with Left Mouse Button highlighted with Grey Colour. The Left-click will be the default Active Button when you turn on Mouse Keys.

- If you want to use Right-Click on an item then you must switch the Active Button by clicking the – (Hyphen) Key from the Num Pad.

- To use or switch back to Left-click as your Active Button use / (Backward Slash) and you can see the Active Key Status in the System Tray.

- To use both Left-Right buttons, press the * (Asterisk) Key.

How To Use Mouse Keys through NUM PAD?

You only need to configure all these settings once and you can watch the following short-video to see Mouse Keys in action.

Watch How To Use Mouse Keys in Windows Tutorial Video @YouTube #TheTeacher

Thumb buttons By default, these buttons move backward or forward in an Internet browser.

Contents

- 1 What is thumb mouse button 4?

- 2 How do you make a thumb button on a mouse?

- 3 What are the three mouse buttons?

- 4 What are the 2 buttons on the side of my mouse?

- 5 Where is the mouse button 5?

- 6 What is left mouse button?

- 7 Which mouse is best for fortnite?

- 8 What is mouse click?

- 9 What is the name of mouse button?

- 10 What is mouse 3 button Valheim?

- 11 What is mouse button configuration?

- 12 What is the middle button on mouse for?

- 13 What does a fire button do on a mouse?

- 14 What does a 6 button mouse do?

- 15 How many buttons are there in mouse?

- 16 What is right button?

- 17 What are the buttons on the side of my Logitech mouse?

- 18 What are the 7 buttons of a mouse?

- 19 Is it right click or right click?

- 20 What mouse does Sypherpk use?

Buttons four and five are called side or thumb buttons as they are often attached to the side of the mouse and controlled with thumb activity. Windows maps forward and backward navigation to these buttons by default which you can use in web browsers and some other programs.

How do you make a thumb button on a mouse?

How to assign functions

- Click Start, and then click Control Panel.

- Double-click Mouse.

- Click the Buttons tab.

- Under Button Assignment, click the box for a button to which you want to assign a function, and then click the function that you want to assign to that button.

- Click Apply, and then click OK.

What are the three mouse buttons?

The typical mouse has 3 buttons: the left, right, and middle (scroll wheel) buttons.

What are the 2 buttons on the side of my mouse?

By extra buttons here we mean the additional two buttons on the side of your computer mouse. Usually, these buttons are programmed as Forward and Backward buttons. Also, most of the modern games call them Mouse Button 4 and Mouse Button 5.

Where is the mouse button 5?

Mouse Button 4 and Mouse Button 5 usually refer to the extra buttons found on the side of the mouse, often near your thumb.

What is left mouse button?

The left button on a mouse is the default button used to click, select, drag to highlight a word and/or object and used as a pointer.

Which mouse is best for fortnite?

Top 8 Gaming Mouse for Fortnite

- Razer DeathAdder V2 Gaming Mouse.

- Razer Viper Ultimate Hyperspeed Lightest Wireless Gaming Mouse.

- Logitech G305 Lightspeed Wireless Gaming Mouse.

- Logitech G Pro Wireless Gaming Mouse.

- Cooler Master MM710 53G Gaming Mouse.

- Logitech G502 Lightspeed Wireless Gaming Mouse.

What is mouse click?

A mouse click is the action of pressing (i.e. ‘clicking’, an onomatopoeia) a button to trigger an action, usually in the context of a graphical user interface (GUI). “Clicking” an onscreen button is accomplished by pressing on the real mouse button while the pointer is placed over the onscreen button’s icon.

What is the name of mouse button?

Most computer mice have at least two mouse buttons. When you press the left one, it is called a left click. When you press the one on the right, it is called a right click. By default, the left button is the main mouse button, and is used for common tasks such as selecting objects and double-clicking.

What is mouse 3 button Valheim?

These are all the default PC controls of Valheim.

Keyboard Controls and Key Bindings of Valheim.

| CONTROL | INPUT |

|---|---|

| Attack | Left Click/Mouse Button 1 |

| Secondary Attack | Middle Click/Scroll Wheel Click/Mouse Button 3 |

| Block | Right Click/Mouse Button 2 |

| Use | E |

What is mouse button configuration?

The installation program allows users to select the type of mouse connected to the system. To configure a different mouse type for the system, use the Mouse Configuration Tool.

What is the middle button on mouse for?

The middle mouse button (which is the scroll wheel on most mice today) is basically used for two purposes on the web: first, open links in new tabs, and second, close open tabs.

What does a fire button do on a mouse?

The fire power button acts like you clicked the left mouse button about three times. It’s supposed to help gamers who like to double tap, but it’s also good for accessing files very quickly.

What does a 6 button mouse do?

if you click the 6th button then play on your cursor on the screen each click (6th button)you will notice the ranges how far can your cursor travel from left to right or up/down.

How many buttons are there in mouse?

Many standard mice have two buttons: a left button and a right button. If you are right handed, the left mouse button will be directly under your index finger when you place your hand on the mouse.

What is right button?

Sometimes abbreviated as RMB (right mouse button), the right-click is the action of pressing down on the right mouse button. The right-click provides additional functionality to a computer’s mouse, usually in the form of a drop-down menu (context or shortcut menu) containing additional options.

What are the buttons on the side of my Logitech mouse?

The mouse has no shortage of buttons — seven total — to turn your hand into a control center for shortcuts that you assign using the Logitech SetPoint software. The two extra buttons for your thumb on the left side also make it really easy to flick back and forward in a web browser or media player.

What are the 7 buttons of a mouse?

The optical resolution of the mouse is 5500dpi, allowing you to control the color of the mouse more freely. 【7 Buttons】7 buttons are left, right, wheel, DPI, fire button, forward, retreat, operation is more convenient, fire button can carry out triple attack.

| Connectivity Technology | USB |

|---|---|

| Number of Buttons | 7 |

Is it right click or right click?

To right-click or to right-click on something means to press the right-hand button on a computer mouse. All you have to do is right-click on the desktop and select New Folder.

What mouse does Sypherpk use?

WHAT MOUSE DOES SYPHERPK USE? SypherPK uses a Razer Viper Ultimate mouse. The Razer Viper Ultimate is a wireless, ambidextrous gaming mouse that is fitted with a Razer 5G optical sensor that offers a range of up to 20,000 dpi.

Updated: 08/02/2020 by

A mouse button is one or more buttons found on the front portion of a computer mouse that allows a computer user to perform an action. For example, a user may be required to click the mouse button to open a file, or hold the mouse button down to highlight text.

Mouse button actions

Today, every mouse has at least two mouse buttons, and may have additional buttons found on the side of the mouse.

Left mouse button

- Default mouse button on most operating systems and programs.

- Used to click, select, or open an object on the computer. For example, you would left-click to open a link in a browser or double left-click (double-click) to open a program on a Microsoft Windows operating system.

- Left-clicking and holding down the button while dragging the mouse highlights text.

- In a spreadsheet, clicking a cell with the left mouse button makes it the active cell.

- In a game, the left button is used as the action button. For example, in a shooter game, the left button is often used to shoot a gun.

Right mouse button

The right mouse button is used to give additional information, or the properties of a right-clicked item. For example, if you right-click anything highlighted, you are given a menu that lets you copy the highlighted text or another object.

Middle mouse button or wheel button

Many computer mice with wheels can also use the wheel as a button. Pressing down on the mouse wheel acts as a button and its action depends on the software installed with the mouse. By default, the middle button is used to open a link in a browser in a new tab.

Thumb buttons

For mice with thumb buttons, these buttons can be programmed to perform any action. By default, these buttons move backward or forward in an Internet browser.

Other buttons

There are also some computer mice that have more than the buttons listed above. For example, a gaming mouse can have different buttons that can be programmed to perform any number of actions in a game.

Tip

See our click definition for further examples of the type of clicking that can be done with the mouse buttons.

Button, Click, Mouse, Mouse terms

Содержание

- Где находится клавиша ПКМ на клавиатуре

- Что такое ПКМ на компьютере | RMB

- Аналог кнопки ПКМ на клавиатуре: клавиша контекстного меню

- Mouse button

- Mouse button actions

- Left mouse button

- Right mouse button

- Middle mouse button or wheel button

- Thumb buttons

- Other buttons

- right mouse button

- Смотреть что такое «right mouse button» в других словарях:

- Где кнопка пкм на клавиатуре на ноутбуке

- Что такое ПКМ на компьютере | RMB

- Аналог кнопки ПКМ на клавиатуре: клавиша контекстного меню

- Что такое «ПКМ»? Что нужно знать и понимать. Инструкция для новичков

- Что такое «ПКМ» на компьютере

- Что такое «ПКМ» на клавиатуре

- Использование контекстных меню

- Самое главное заблуждение

- Что делать если мышь нажимает сразу ЛКМ и ПКМ?

- ЛКМ — это… Что такое ЛКМ?

- Расшифровка названий

- См. также

- Ссылки

- Почему при нажатии ЛКМ происходит действие как для ПКМ?

- Пкм на клавиатуре

Где находится клавиша ПКМ на клавиатуре

Автор: Юрий Белоусов · 10.05.2019

При чтении инструкций по выполнению каких-либо действий за компьютером, в них часто можно встретить аббревиатуру ПКМ. Например, одним из пунктов может быть: «Нажать ПКМ» или «Сделать клик ПКМ». Пользователи же, не зная, что это за клавиша, лезут в интернет, пытаясь выяснить, что это за кнопка ПКМ, где она находится на клавиатуре ПК или ноутбука и как вообще расшифровывается аббревиатура ПКМ.

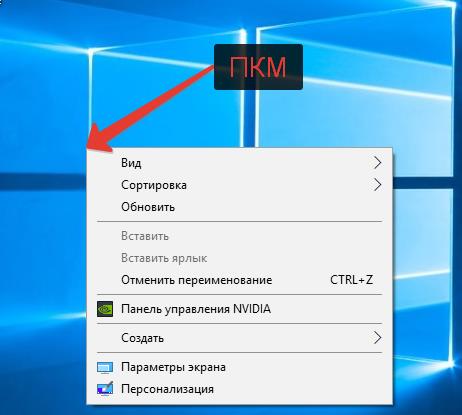

Что такое ПКМ на компьютере | RMB

Что такое ПКМ на компьютере и что значит данное обозначение?

ПКМ – это Правая Кнопка Мыши (на английском: RMB — right mouse button). Кнопка ПКМ отвечает за вызов дополнительных функций, настроек и свойств. На сайтах, в большинстве программ, приложений, а также в OS Windows, при нажатии ПКМ произойдет вызов контекстного меню.

Пример вывода контекстного меню при нажатии ПКМ на рабочем столе Windows:

Если кто испытывает сложности при определении где право, а где лево, смотрите фото, где обозначены ПКМ и ЛКМ:

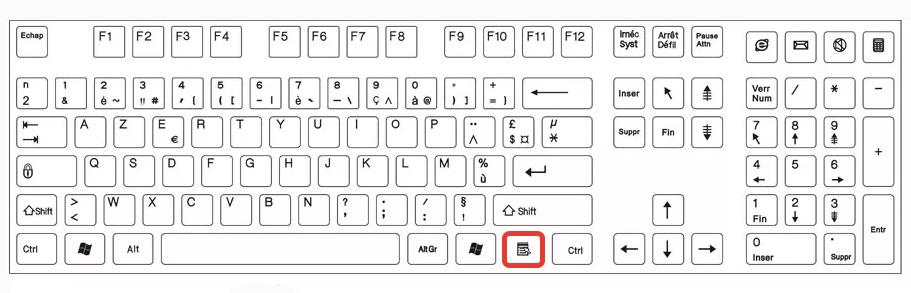

Аналог кнопки ПКМ на клавиатуре: клавиша контекстного меню

Когда у пользователя нет возможности сделать клик правой кнопкой мыши по каким-либо причинам, например, если вдруг ПКМ не работает, то можно использовать аналог кнопки ПКМ на клавиатуре, которая полноценно ее заменяет и выполняет все те же функции по выводу контекстного меню файла или объекта.

Shift + F10 – сочетание горячих клавиш для вызова контекстного меню с клавиатуры, без использования правой кнопки мыши (ПКМ).

Помимо упомянутого выше сочетания клавиш, на современных клавиатурах есть полноценная кнопка вызова контекстного меню. Расположена она между правыми кнопками Windows и Ctrl (см. рисунок ниже) и выглядит как список со стрелочкой, указывающей на один из пунктов.

Надеюсь, данная статья помогла разобраться с тем, что значит ПКМ, где находится данная кнопка, а также как заменить управление работой правой кнопкой мышки через использование клавиш на клавиатуре.

Не нашли ответ? Тогда воспользуйтесь формой поиска:

Источник

Mouse button

A mouse button is one or more buttons found on the front portion of a computer mouse that allows a computer user to perform an action. For example, a user may be required to click the mouse button to open a file, or hold the mouse button down to highlight text.

Mouse button actions

Today, every mouse has at least two mouse buttons, and may have additional buttons found on the side of the mouse.

Left mouse button

- Default mouse button on most operating systems and programs.

- Used to click, select, or open an object on the computer. For example, you would left-click to open a link in a browser or double left-click (double-click) to open a program on a Microsoft Windows operating system.

- Left-clicking and holding down the button while dragging the mouse highlights text.

- In a spreadsheet, clicking a cell with the left mouse button makes it the active cell.

- In a game, the left button is used as the action button. For example, in a shooter game, the left button is often used to shoot a gun.

Right mouse button

The right mouse button is used to give additional information, or the properties of a right-clicked item. For example, if you right-click anything highlighted, you are given a menu that allows you to copy the highlighted text or another object.

Middle mouse button or wheel button

Many computer mice with wheels can also use the wheel as a button. Pressing down on the mouse wheel acts as a button and its action depends on the software installed with the mouse. By default, the middle button is used to open a link in a browser in a new tab.

Thumb buttons

For mice with thumb buttons, these buttons can be programmed to perform any action. By default, these buttons move backward or forward in an Internet browser.

Other buttons

There are also some computer mice that have more than the buttons listed above. For example, a gaming mouse can have different buttons that can be programmed to perform any number of actions in a game.

See our click definition for further examples of the type of clicking that can be done with the mouse buttons.

Источник

right mouse button

Универсальный англо-русский словарь . Академик.ру . 2011 .

Смотреть что такое «right mouse button» в других словарях:

Mouse button — One button mouse Three button mouse … Wikipedia

Mouse chording — is the capability of performing actions when multiple mouse buttons are held down, much like a chorded keyboard. Like mouse gestures, chorded actions may lack feedback and affordance and would therefore offer no way for users to discover possible … Wikipedia

mouse — [ maus ] (plural mice [ maıs ] ) noun count ** 1. ) a small furry animal with a long tail: The cat s caught another mouse. 2. ) (plural mouses or mice) a small object that you move in order to do things on a computer screen. When you press on a… … Usage of the words and phrases in modern English

Mouse (computing) — A computer mouse with the most common standard features: two buttons and a scroll wheel, which can also act as a third button In computing, a mouse is a pointing device that functions by detecting two dimensional motion relative to its supporting … Wikipedia

Mouse gesture — In computing, a mouse gesture is a way of combining computer mouse movements and clicks which the software recognizes as a specific command. Mouse gestures can provide quick access to common functions of a program. They can also be useful for… … Wikipedia

button — but|ton1 S2 [ˈbʌtn] n [Date: 1300 1400; : Old French; Origin: boton, from boter; BUTT2] 1.) a small round flat object on your shirt, coat etc which you pass through a hole to fasten it ▪ small pearl buttons ▪ A button was missing from his shirt.… … Dictionary of contemporary English

right-drag — verb To drag an item using the right mouse button … Wiktionary

right-click — rightˈ click intransitive verb To press and release the right hand button on a computer mouse noun An act of doing this • • • Main Entry: ↑right * * * right click UK US verb [intransitive] [present tense I/you/we/they ri … Useful english dictionary

right-click — right clicks, right clicking, right clicked VERB To right click or to right click on something means to press the right hand button on a computer mouse. [COMPUTING] [V on n] All you have to do is right click on the desktop and select New Folder.… … English dictionary

right-click — v [I] to press the right hand button on a computer ↑mouse to make the computer do something right click on ▪ Right click on the image to save it … Dictionary of contemporary English

button — but|ton1 [ bʌtn ] noun count ** 1. ) a small round object that is used for fastening clothes by pushing it through a hole: He had undone the top button of his shirt. a blouse with small pearl buttons 2. ) a small object that you press to make a… … Usage of the words and phrases in modern English

Источник

Где кнопка пкм на клавиатуре на ноутбуке

Автор: Юрий Белоусов · 10.05.2019

При чтении инструкций по выполнению каких-либо действий за компьютером, в них часто можно встретить аббревиатуру ПКМ. Например, одним из пунктов может быть: «Нажать ПКМ» или «Сделать клик ПКМ». Пользователи же, не зная, что это за клавиша, лезут в интернет, пытаясь выяснить, что это за кнопка ПКМ, где она находится на клавиатуре ПК или ноутбука и как вообще расшифровывается аббревиатура ПКМ.

Что такое ПКМ на компьютере | RMB

Что такое ПКМ на компьютере и что значит данное обозначение?

ПКМ – это Правая Кнопка Мыши (на английском: RMB — right mouse button). Кнопка ПКМ отвечает за вызов дополнительных функций, настроек и свойств. На сайтах, в большинстве программ, приложений, а также в OS Windows, при нажатии ПКМ произойдет вызов контекстного меню.

Пример вывода контекстного меню при нажатии ПКМ на рабочем столе Windows:

Если кто испытывает сложности при определении где право, а где лево, смотрите фото, где обозначены ПКМ и ЛКМ:

Аналог кнопки ПКМ на клавиатуре: клавиша контекстного меню

Когда у пользователя нет возможности сделать клик правой кнопкой мыши по каким-либо причинам, например, если вдруг ПКМ не работает, то можно использовать аналог кнопки ПКМ на клавиатуре, которая полноценно ее заменяет и выполняет все те же функции по выводу контекстного меню файла или объекта.

Shift + F10 – сочетание горячих клавиш для вызова контекстного меню с клавиатуры, без использования правой кнопки мыши (ПКМ).

Помимо упомянутого выше сочетания клавиш, на современных клавиатурах есть полноценная кнопка вызова контекстного меню. Расположена она между правыми кнопками Windows и Ctrl (см. рисунок ниже) и выглядит как список со стрелочкой, указывающей на один из пунктов.

Надеюсь, данная статья помогла разобраться с тем, что значит ПКМ, где находится данная кнопка, а также как заменить управление работой правой кнопкой мышки через использование клавиш на клавиатуре.

Не нашли ответ? Тогда воспользуйтесь формой поиска:

Что такое «ПКМ»? Что нужно знать и понимать. Инструкция для новичков

Конечно, многие из новоявленных пользователей, впервые столкнувшихся с объектно-ориентированными системами на основе доступа к основным функциям посредством дополнительных меню, спрашивают о том, что такое «ПКМ». К сожалению, нужно сразу огорчить всех юзеров этого уровня. Не знать, что такое «ПКМ», — значит, не знать вообще ничего.

Что такое «ПКМ» на компьютере

Откровенно говоря, любой пользователь, не знающий, как расшифровывается это сокращение, просто приводит в состояние крайнего недоумения! Ну неужели, даже при самой примитивной попытке интерпретации данного сокращения не может прийти на ум нечто вроде «Правого клика мышью» или аналогичного «Правой кнопки мыши»?

Это и есть понимание того, что такое «ПКМ». Обычно посредством такого клика вызываются дополнительные меню (об этом будет сказано чуть позже). Но для дедушек и бабушек, совершенно не знакомых с устройством и функционированием операционной системы и использованием ее возможностей через стандартные или дополнительные средства, все же попытаемся рассмотреть этот вопрос наиболее подробно.

Что такое «ПКМ» на клавиатуре

Случается и по-другому. Иногда многие своенравные и якобы всезнающие пользователи задаются вопросом о том, что такое «ПКМ» на клавиатуре ноутбука. Ну, что тут можно ответить? Напрашивается только фраза персонажа Владимира Зеленского из «95 квартала», сказанная ведущему шоу насчет определения самого умного интеллектуала в студии (из соображений корректности напоминать ее не будем).

Да, что это на клавиатуре? Просто набор символов. Правый клик к клавиатуре не имеет абсолютно никакого отношения. Иногда, правда, встречаются вопросы типа этого (что такое «ПКМ»?) в разделах форумов или помощи по программному обеспечению, но там дается четкий ответ, что если ты не знаешь этого, сюда лучше не заходить вообще. Кстати сказать, и сама формулировка вопроса вызывает достаточно много нареканий.

Тут любому, даже начинающему юзеру, следует усвоить, что понятия «ПКМ» и «ЛКМ» различаются только определением кнопки мыши, на которую будет производиться нажатие в данный момент (правая или левая).

Использование контекстных меню

С вызываемыми меню, называемыми контекстными, тоже не все так просто. Обычно они содержат намного больше средств доступа к выделяемому объекту (хоть это и не всегда так).

Для простейшего примера можно использовать открытие файла с правами админа в том же «Проводнике» или применение способа просмотра свойств файла или папки (например, размера, длительности звучания или показа, не считая характеристик развертки или битрейта, если это файлы мультимедиа).

Самое главное заблуждение

Наконец, большинство пользователей ассоциирует меню правого клика с использованием ссылки на тот или иной параметр или настройку с панацеей от всех проблем, которые могут иметь компьютерные системы.

Дело в том, что для доступа к некоторым функциям самой ОС или некоторым возможностям программ этого будет явно недостаточно. Поэтому, прежде чем приступать к изучению компьютерной терминологии, следует четко разобраться, что собой представляют программные продукты и «железные» компоненты, среди которых, кстати, присутствует и манипулятор, называемый мышью. Ею управлять не у всех получается с первого раза. Но пара тренировок – и все будет нормально. И даже правый или левый клик при условии наличия 3-кнопочной мыши будут производиться совершенно элементарно после нескольких предварительных манипуляций.

Остается надеяться, что после прочтения данного материала ни у кого не возникнет вопроса о том, что собой представляет сокращение типа «ПКМ» применительно к его использованию и вызову соответствующих контекстных меню с дополнительными строками доступа к недокументированным или основным настройкам и параметрам.

Кроме всего прочего, следует учесть, что контекстные меню (в отличие от основных) меняют свою структуру только в случае инсталляции программ, самопроизвольно интегрирующих свои команды в систему. Самыми простыми примерами могут служить те же программы-архиваторы вроде WinRAR, WinZIP или 7-Zip. Но и другие приложения способны менять порядок строк и команд, не говоря уже о специализированных утилитах, которые созданы исключительно с этой целью.

Что делать если мышь нажимает сразу ЛКМ и ПКМ?

Выкинуть эту мышь КЕМ

Есть мышки по 200р есть по 3к. Не мудрено что живут разное время.

Осмотри внимательно мышь. Может быть что-то попало между левой и правой клавишами.

Я заметил, что это появляется ток когда сильно жмёшь на кнопку… Когда чуть чуть нажимаешь и легко, то тогда все нормально.. Такая же проблема и не знаю что делать

ЛКМ — это… Что такое ЛКМ?

Лакокрасочные материалы (ЛКМ) — это композиционные составы, наносимые на отделываемые поверхности в жидком или порошкообразном виде равномерными тонкими слоями и образующие после высыхания и отвердения пленку, имеющую прочное сцепление с основанием. Сформировавшуюся пленку называют лакокрасочным покрытием, свойством которого является защита поверхности от внешних воздействий (воды, коррозии, вредных веществ), придание ей определенных вида, цвета и фактуры.

ЛКМ подразделяются на следующие группы

Расшифровка названий

Название ЛКМ в России носит аббревиатурный характер и состоит из комбинации букв и цифр.

Например, алкидная эмаль ПФ-115. Буквенное обозначение «ПФ» говорит о том, что эмаль изготовлена на основе пентафталевого связующего, первая цифра 1 — для наружного применения, 15 — каталожный номер.

По типу основного связующего лакокрасоные материалы подразделяются на:

- АК — акриловые

- АУ — алкидно-уретановая

- АЦ — ацетилцеллюлозная

- БТ — битумные

- ВА — поливинилацетатная

- ГФ — глифталевая

- ЖС — силикатные

- КО — кремнийорганические

- КФ — канифольная

- КЧ — каучуковая

- МЛ — меламиноалкидные

- НП — нефтеполимерная

- НЦ — нитроцеллюлозные

- ПЭ — полиэфирные

- УР — полиуретановая

- ХВ — хлорвиниловые

- ШЛ — шеллачные

- ЭП — эпоксидная

Также перед буквенным обозначением могут стоять дополнительные буквы:

- ВД — водно-дисперсионная

- ВЭ — водоэмульсионная

- Б — без растворителя

- В — водоразбавляемая.

- 0 — грунтовка

- 00 — шпатлевка

- 1 — атмосферостойкая (для наружного применения)

- 2 — ограниченно атмосферостойкая (для внутреннего применения)

- 3 — консервационные краски

- 4 — водостойкие

- 5 — специальные эмали и краски

- 6 — маслобензостойкие

- 7 — химически стойкие

- 8 — термостойкие

- 9 — электроизоляционные и электропроводные.

См. также

Ссылки

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.

Почему при нажатии ЛКМ происходит действие как для ПКМ?

В настройках мыши выставил для левшей.

Панель управления, мышь.

Панель управления->мышь

Изменить там настройки

Пкм на клавиатуре

Автор Nick Kamaev задал вопрос в разделе Другое

на клавиатуре какая кнопка ПКМ и получил лучший ответ

Ответ от Игорь[гуру]

Это не на клавиатуре. ПКМ – правая кнопка мыши. ЛКМ – левая кнопка мыши.

спросили в Другое

как включить веб камеру на ноутбуке

Инструкция, как включить веб-камеру на ноутбуке:

1. Для начала, нужно проверить работает

подробнее.

Способ I: Форматирование через соответствующий интерфейс

подробнее.

Источник

This article is about the item of computer hardware. For the pointer it controls, see Pointer (user interface).

A computer mouse with the most common features: two buttons (left and right) and a scroll wheel, which can also act as a third button.

A computer mouse is a hand-held pointing device that detects two-dimensional motion relative to a surface. This motion is typically translated into the motion of a pointer on a display, which allows a smooth control of the graphical user interface. The first public demonstration of a mouse controlling a computer system was in 1968. Originally wired to a computer, many modern mice are cordless, relying on short-range radio communication with the connected system. Mice originally used a ball rolling on a surface to detect motion, but modern mice often have optical sensors that have no moving parts. In addition to moving a cursor, computer mice have one or more buttons to allow operations such as selection of a menu item on a display. Mice often also feature other elements, such as touch surfaces and «wheels», which enable additional control and dimensional input.

Naming

The earliest known publication of the term mouse as referring to a computer pointing device is in Bill English’s July 1965 publication, «Computer-Aided Display Control» likely originating from its resemblance to the shape and size of a mouse, a rodent, with the cord resembling its tail.[1][2][3]

The plural for the small rodent is always «mice» in modern usage. The plural of a computer mouse is either «mouses» or «mice» according to most dictionaries, with «mice» being more common.[4] The first recorded plural usage is «mice»; the online Oxford Dictionaries cites a 1984 use, and earlier uses include J. C. R. Licklider‘s «The Computer as a Communication Device» of 1968.[5] The term computer mouses may be used informally in some cases. Although, the plural of mouse (small rodent) is mice, the two words have undergone a differentiation through usage.

History

The trackball, a related pointing device, was invented in 1946 by Ralph Benjamin as part of a post-World War II-era fire-control radar plotting system called Comprehensive Display System (CDS). Benjamin was then working for the British Royal Navy Scientific Service. Benjamin’s project used analog computers to calculate the future position of target aircraft based on several initial input points provided by a user with a joystick. Benjamin felt that a more elegant input device was needed and invented what they called a «roller ball» for this purpose.[6][7]

The device was patented in 1947,[7] but only a prototype using a metal ball rolling on two rubber-coated wheels was ever built, and the device was kept as a military secret.[6]

Another early trackball was built by Kenyon Taylor, a British electrical engineer working in collaboration with Tom Cranston and Fred Longstaff. Taylor was part of the original Ferranti Canada, working on the Royal Canadian Navy‘s DATAR (Digital Automated Tracking and Resolving) system in 1952.[8]

DATAR was similar in concept to Benjamin’s display. The trackball used four disks to pick up motion, two each for the X and Y directions. Several rollers provided mechanical support. When the ball was rolled, the pickup discs spun and contacts on their outer rim made periodic contact with wires, producing pulses of output with each movement of the ball. By counting the pulses, the physical movement of the ball could be determined. A digital computer calculated the tracks and sent the resulting data to other ships in a task force using pulse-code modulation radio signals. This trackball used a standard Canadian five-pin bowling ball. It was not patented, since it was a secret military project.[9][10]

File:Mouse-patents-englebart-rid.png Early mouse patents. From left to right: Opposing track wheels by Engelbart, November 1970, Template:US Patent. Ball and wheel by Rider, September 1974, Template:US Patent. Ball and two rollers with spring by Opocensky, October 1976, Template:US Patent

Douglas Engelbart of the Stanford Research Institute (now SRI International) has been credited in published books by Thierry Bardini,[11] Paul Ceruzzi,[12] Howard Rheingold,[13] and several others[14][15][16] as the inventor of the computer mouse. Engelbart was also recognized as such in various obituary titles after his death in July 2013.[17][18][19][20]