Can a.out both run on little-endian and big-endian system?

No, because pretty much any two CPUs that are so different as to have different endian-ness will not run the same instruction set. C++ isn’t Java; you don’t compile to something that gets compiled or interpreted. You compile to the assembly for a specific CPU. And endian-ness is part of the CPU.

But that’s outside of endian issues. You can compile that program for different CPUs and those executables will work fine on their respective CPUs.

What makes a system little-endian or big-endian?

As far as C or C++ is concerned, the CPU. Different processing units in a computer can actually have different endians (the GPU could be big-endian while the CPU is little endian), but that’s somewhat uncommon.

If I want to write a byte-order independent C++ program, what do I need to take into account?

As long as you play by the rules of C or C++, you don’t have to care about endian issues.

Of course, you also won’t be able to load files directly into POD structs. Or read a series of bytes, pretend it is a series of unsigned shorts, and then process it as a UTF-16-encoded string. All of those things step into the realm of implementation-defined behavior.

There’s a difference between «undefined» and «implementation-defined» behavior. When the C and C++ spec say something is «undefined», it basically means all manner of brokenness can ensue. If you keep doing it, (and your program doesn’t crash) you could get inconsistent results. When it says that something is defined by the implementation, you will get consistent results for that implementation.

If you compile for x86 in VC2010, what happens when you pretend a byte array is an unsigned short array (ie: unsigned char *byteArray = ...; unsigned short *usArray = (unsigned short*)byteArray) is defined by the implementation. When compiling for big-endian CPUs, you’ll get a different answer than when compiling for little-endian CPUs.

In general, endian issues are things you can localize to input/output systems. Networking, file reading, etc. They should be taken care of in the extremities of your codebase.

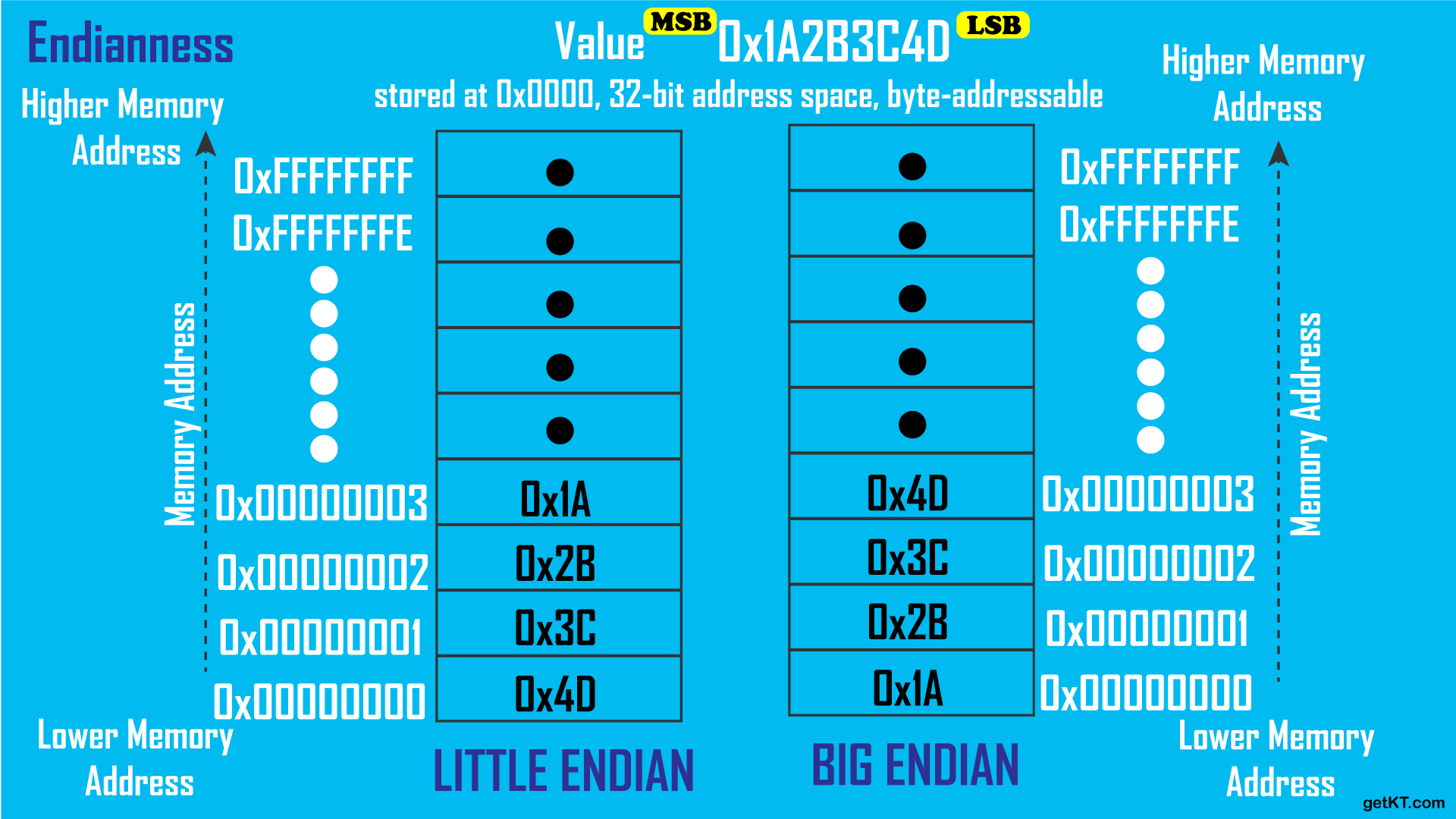

In computing, endianness is the order or sequence of bytes of a word of digital data in computer memory. Endianness is primarily expressed as big-endian (BE) or little-endian (LE). A big-endian system stores the most significant byte of a word at the smallest memory address and the least significant byte at the largest.

A little-endian system, in contrast, stores the least-significant byte at the smallest address.[1][2][3] Bi-endianness is a feature supported by numerous computer architectures that feature switchable endianness in data fetches and stores or for instruction fetches.

Other orderings are generically called middle-endian or mixed-endian.[4][5][6][7]

Endianness may also be used to describe the order in which the bits are transmitted over a communication channel[citation needed], e.g., big-endian in a communications channel transmits the most significant bits first.[8][citation needed] Bit-endianness is seldom used in other contexts.

Etymology[edit]

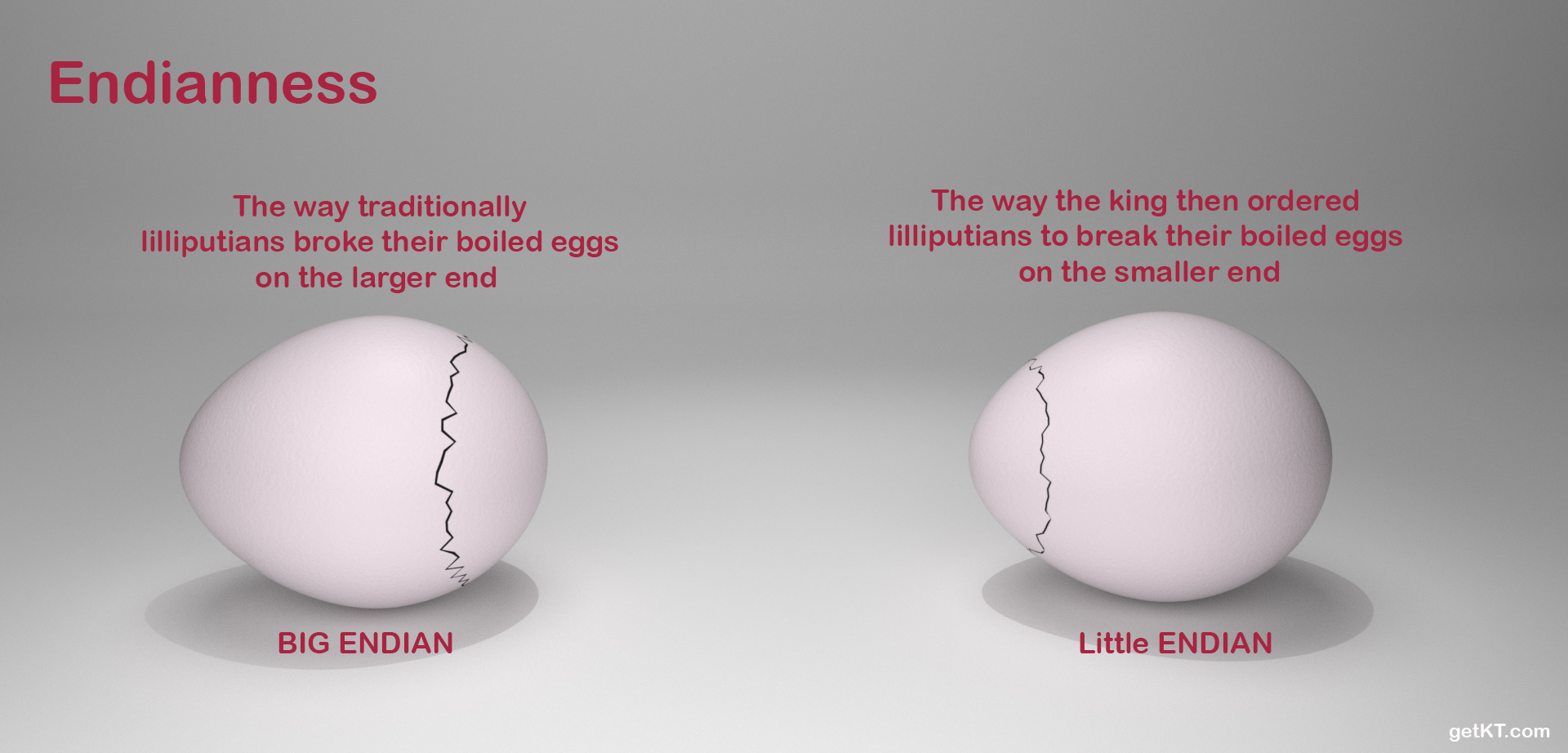

The adjective endian comes from the 1726 novel Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift where characters known as Lilliputians are required by an imperial edict to break the shell of a boiled egg from the little end; those who rebel and open eggs from the big end are called «Big-Endians».

Danny Cohen introduced the terms big-endian and little-endian into computer science for data ordering in an Internet Experiment Note published in 1980.[9]

The adjective endian has its origin in the writings of 18th century Anglo-Irish writer Jonathan Swift. In the 1726 novel Gulliver’s Travels, he portrays the conflict between sects of Lilliputians divided into those breaking the shell of a boiled egg from the big end or from the little end. Because the emperor’s son had cut his finger while opening an egg from the big end, doing so was prohibited by an imperial edict; those who rebelled and did so were called «Big-Endians» (Swift did not use the term Little-Endians in the work).[10][11] Cohen makes the connection to Gulliver’s Travels explicit in the appendix to his 1980 note.

Previously the name byte sex was sometimes used for the same concept.[12][13][14]

Overview[edit]

Computers store information in various-sized groups of binary bits. Each group is assigned a number, called its address, that the computer uses to access that data. On most modern computers, the smallest data group with an address is eight bits long and is called a byte. Larger groups comprise two or more bytes, for example, a 32-bit word contains four bytes. There are two possible ways a computer could number the individual bytes in a larger group, starting at either end. Both types of endianness are in widespread use in digital electronic engineering. The initial choice of endianness of a new design is often arbitrary, but later technology revisions and updates perpetuate the existing endianness to maintain backward compatibility.

Internally, any given computer will work equally well regardless of what endianness it uses since its hardware will consistently use the same endianness to both store and load its data. For this reason, programmers and computer users normally ignore the endianness of the computer they are working with. However, endianness can become an issue when moving data external to the computer – as when transmitting data between different computers, or a programmer investigating internal computer bytes of data from a memory dump – and the endianness used differs from expectation. In these cases, the endianness of the data must be understood and accounted for.

Big-endian

Little-endian

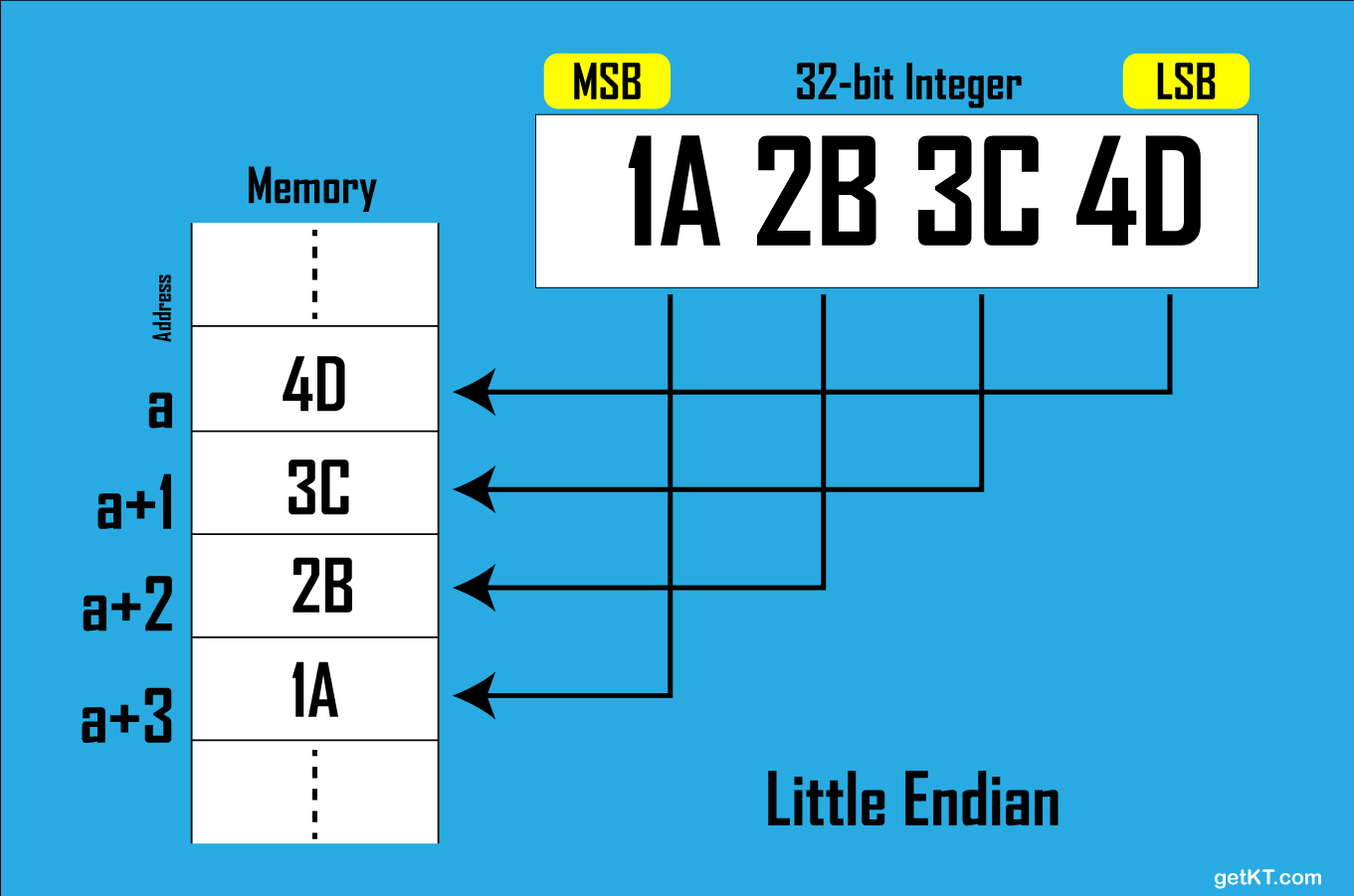

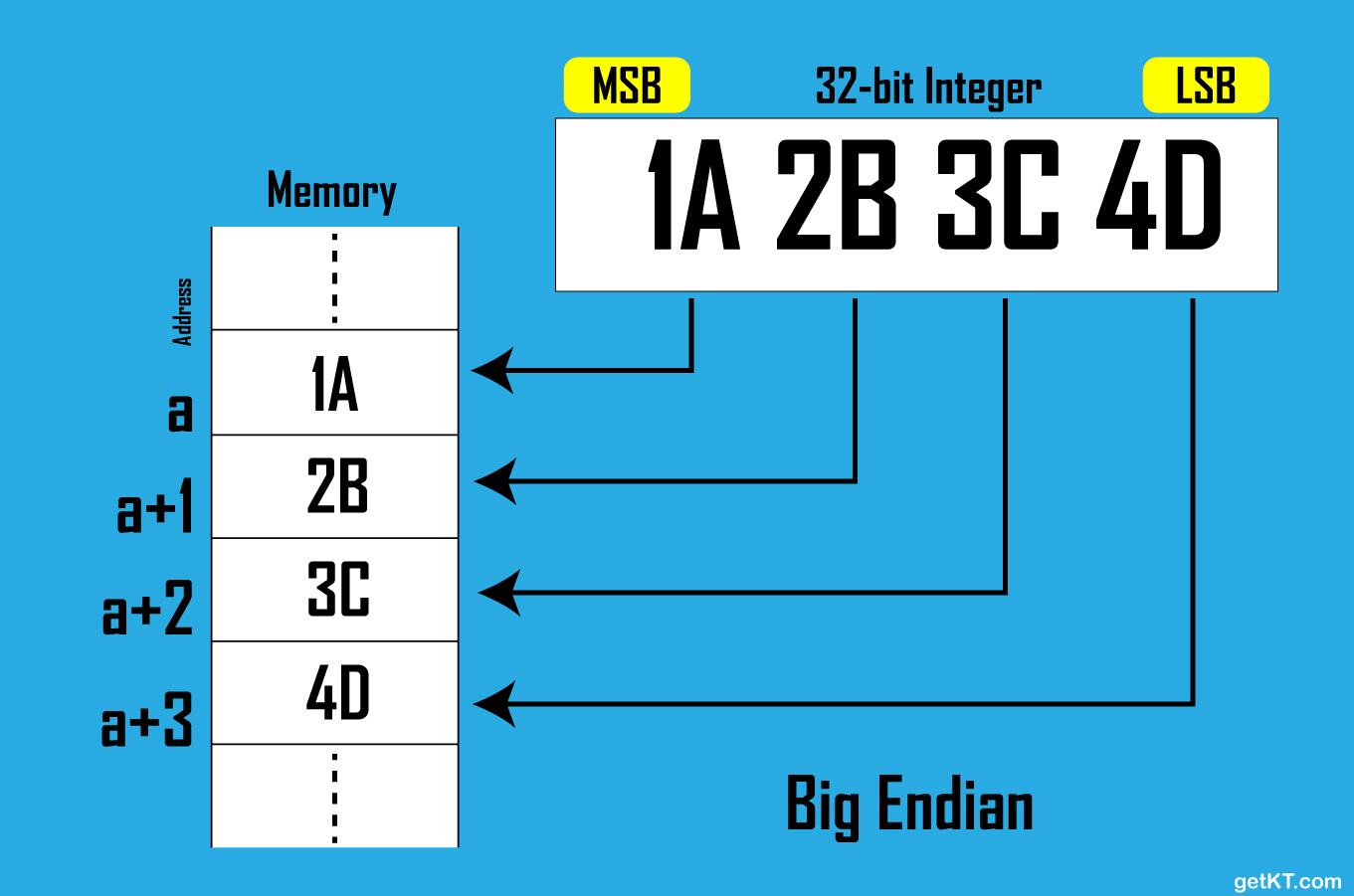

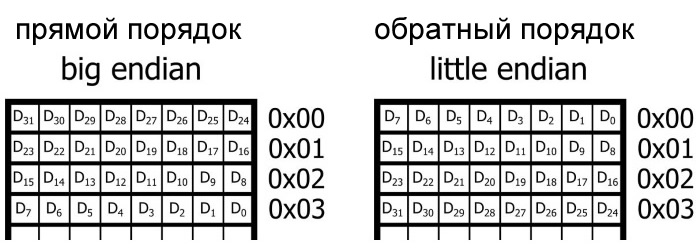

These two diagrams show how two computers using different endianness store a 32-bit (four byte) integer with the value of 0x0A0B0C0D. In both cases, the integer is broken into four bytes, 0x0A, 0x0B, 0x0C, and 0x0D, and the bytes are stored in four sequential byte locations in memory, starting with the memory location with address a, then a + 1, a + 2, and a + 3. The difference between big- and little-endian is the order of the four bytes of the integer being stored.

The left-side diagram shows a computer using big-endian. This starts the storing of the integer with the most-significant byte, 0x0A, at address a, and ends with the least-significant byte, 0x0D, at address a + 3.

The right-side diagram shows a computer using little-endian. This starts the storing of the integer with the least-significant byte, 0x0D, at address a, and ends with the most-significant byte, 0x0A, at address a + 3.

Since each computer uses its same endianness to both store and retrieve the integer, the results will be the same for both computers. Issues may arise when memory is addressed by bytes instead of integers, or when memory contents are transmitted between computers with different endianness.

Big-endianness is the dominant ordering in networking protocols, such as in the internet protocol suite, where it is referred to as network order, transmitting the most significant byte first. Conversely, little-endianness is the dominant ordering for processor architectures (x86, most ARM implementations, base RISC-V implementations) and their associated memory. File formats can use either ordering; some formats use a mixture of both or contain an indicator of which ordering is used throughout the file.[15]

The styles of big- and little-endian may also be used more generally to characterize the ordering of any representation, e.g. the digits in a numeral system or the sections of a date. Numbers in positional notation are generally written with their digits in left-to-right big-endian order, even in right-to-left scripts. Similarly, programming languages use big-endian digit ordering for numeric literals.

Basics[edit]

Computer memory consists of a sequence of storage cells (smallest addressable units); in machines that support byte addressing, those units are called bytes. Each byte is identified and accessed in hardware and software by its memory address. If the total number of bytes in memory is n, then addresses are enumerated from 0 to n − 1.

Computer programs often use data structures or fields that may consist of more data than can be stored in one byte. In the context of this article where its type cannot be arbitrarily complicated, a «field» consists of a consecutive sequence of bytes and represents a «simple data value» which – at least potentially – can be manipulated by one single hardware instruction. On most systems, the address of a multi-byte simple data value is the address of its first byte (the byte with the lowest address).[note 1]

Another important attribute of a byte being part of a «field» is its «significance».

These attributes of the parts of a field play an important role in the sequence the bytes are accessed by the computer hardware, more precisely: by the low-level algorithms contributing to the results of a computer instruction.

Numbers[edit]

Positional number systems (mostly base 2, or less often base 10[note 2]) are the predominant way of representing and particularly of manipulating integer data by computers. In pure form this is valid for moderate sized non-negative integers, e.g. of C data type unsigned. In such a number system, the value of a digit which it contributes to the whole number is determined not only by its value as a single digit, but also by the position it holds in the complete number, called its significance. These positions can be mapped to memory mainly in two ways:[16]

- decreasing numeric significance with increasing memory addresses (or increasing time), known as big-endian and

- increasing numeric significance with increasing memory addresses (or increasing time), known as little-endian.[note 3]

The integer data that are directly supported by the computer hardware have a fixed width of a low power of 2, e.g. 8 bits ≙ 1 byte, 16 bits ≙ 2 bytes, 32 bits ≙ 4 bytes, 64 bits ≙ 8 bytes, 128 bits ≙ 16 bytes. The low-level access sequence to the bytes of such a field depends on the operation to be performed. The least-significant byte is accessed first for addition, subtraction and multiplication. The most-significant byte is accessed first for division and comparison. See § Calculation order.

For floating-point numbers, see § Floating point.

Text[edit]

When character (text) strings are to be compared with one another, e.g. in order to support some mechanism like sorting, this is very frequently done lexicographically where a single positional element (character) also has a positional value. Lexicographical comparison means almost everywhere: first character ranks highest – as in the telephone book.[note 4]

Integer numbers written as text are always represented most significant digit first in memory, which is similar to big-endian, independently of text direction.

Hardware[edit]

Many historical and extant processors use a big-endian memory representation, either exclusively or as a design option. Other processor types use little-endian memory representation; others use yet another scheme called middle-endian, mixed-endian or PDP-11-endian.

Some instruction sets feature a setting which allows for switchable endianness in data fetches and stores, instruction fetches, or both. This feature can improve performance or simplify the logic of networking devices and software. The word bi-endian, when said of hardware, denotes the capability of the machine to compute or pass data in either endian format.

Dealing with data of different endianness is sometimes termed the NUXI problem.[17] This terminology alludes to the byte order conflicts encountered while adapting UNIX, which ran on the mixed-endian PDP-11,[note 5] to a big-endian IBM Series/1 computer. Unix was one of the first systems to allow the same code to be compiled for platforms with different internal representations. One of the first programs converted was supposed to print out Unix, but on the Series/1 it printed nUxi instead.[18]

The IBM System/360 uses big-endian byte order, as do its successors System/370, ESA/390, and z/Architecture. The PDP-10 uses big-endian addressing for byte-oriented instructions. The IBM Series/1 minicomputer uses big-endian byte order.

The Datapoint 2200 used simple bit-serial logic with little-endian to facilitate carry propagation. When Intel developed the 8008 microprocessor for Datapoint, they used little-endian for compatibility. However, as Intel was unable to deliver the 8008 in time, Datapoint used a medium-scale integration equivalent, but the little-endianness was retained in most Intel designs, including the MCS-48 and the 8086 and its x86 successors.[19][20] The DEC Alpha, Atmel AVR, VAX, the MOS Technology 6502 family (including Western Design Center 65802 and 65C816), the Zilog Z80 (including Z180 and eZ80), the Altera Nios II, and many other processors and processor families are also little-endian.

The Motorola 6800 / 6801, the 6809 and the 68000 series of processors used the big-endian format.

The Intel 8051, unlike other Intel processors, expects 16-bit addresses for LJMP and LCALL in big-endian format; however, xCALL instructions store the return address onto the stack in little-endian format.[21]

SPARC historically used big-endian until version 9, which is bi-endian.

Similarly early IBM POWER processors were big-endian, but the PowerPC and Power ISA descendants are now bi-endian.

The ARM architecture was little-endian before version 3 when it became bi-endian.

Newer architectures[edit]

The IA-32 and x86-64 instruction set architectures use the little-endian format. Other instruction set architectures that follow this convention, allowing only little-endian mode, include Nios II, Andes Technology NDS32, and Qualcomm Hexagon.

Solely big-endian architectures include the IBM z/Architecture and OpenRISC.

Some instruction set architectures are «bi-endian» and allow running software of either endianness; these include Power ISA, SPARC, ARM AArch64, C-Sky, and RISC-V. IBM AIX and IBM i run in big-endian mode on bi-endian Power ISA; Linux originally ran in big-endian mode, but by 2019, IBM had transitioned to little-endian mode for Linux to ease the porting of Linux software from x86 to Power.[22][23] SPARC has no relevant little-endian deployment, as both Oracle Solaris and Linux run in big-endian mode on bi-endian SPARC systems, and can be considered big-endian in practice. ARM, C-Sky, and RISC-V have no relevant big-endian deployments, and can be considered little-endian in practice.

Bi-endianness[edit]

Some architectures (including ARM versions 3 and above, PowerPC, Alpha, SPARC V9, MIPS, Intel i860, PA-RISC, SuperH SH-4 and IA-64) feature a setting which allows for switchable endianness in data fetches and stores, instruction fetches, or both. This feature can improve performance or simplify the logic of networking devices and software. The word bi-endian, when said of hardware, denotes the capability of the machine to compute or pass data in either endian format.

Many of these architectures can be switched via software to default to a specific endian format (usually done when the computer starts up); however, on some systems, the default endianness is selected by hardware on the motherboard and cannot be changed via software (e.g. the Alpha, which runs only in big-endian mode on the Cray T3E).

Note that the term bi-endian refers primarily to how a processor treats data accesses. Instruction accesses (fetches of instruction words) on a given processor may still assume a fixed endianness, even if data accesses are fully bi-endian, though this is not always the case, such as on Intel’s IA-64-based Itanium CPU, which allows both.

Note, too, that some nominally bi-endian CPUs require motherboard help to fully switch endianness. For instance, the 32-bit desktop-oriented PowerPC processors in little-endian mode act as little-endian from the point of view of the executing programs, but they require the motherboard to perform a 64-bit swap across all 8 byte lanes to ensure that the little-endian view of things will apply to I/O devices. In the absence of this unusual motherboard hardware, device driver software must write to different addresses to undo the incomplete transformation and also must perform a normal byte swap.

Some CPUs, such as many PowerPC processors intended for embedded use and almost all SPARC processors, allow per-page choice of endianness.

SPARC processors since the late 1990s (SPARC v9 compliant processors) allow data endianness to be chosen with each individual instruction that loads from or stores to memory.

The ARM architecture supports two big-endian modes, called BE-8 and BE-32.[24] CPUs up to ARMv5 only support BE-32 or word-invariant mode. Here any naturally aligned 32-bit access works like in little-endian mode, but access to a byte or 16-bit word is redirected to the corresponding address and unaligned access is not allowed. ARMv6 introduces BE-8 or byte-invariant mode, where access to a single byte works as in little-endian mode, but accessing a 16-bit, 32-bit or (starting with ARMv8) 64-bit word results in a byte swap of the data. This simplifies unaligned memory access as well as memory-mapped access to registers other than 32 bit.

Many processors have instructions to convert a word in a register to the opposite endianness, that is, they swap the order of the bytes in a 16-, 32- or 64-bit word. All the individual bits are not reversed though.

Recent Intel x86 and x86-64 architecture CPUs have a MOVBE instruction (Intel Core since generation 4, after Atom),[25] which fetches a big-endian format word from memory or writes a word into memory in big-endian format. These processors are otherwise thoroughly little-endian.

There are also devices which use different formats in different places. For instance, the BQ27421 Texas Instruments battery gauge uses the little-endian format for its registers and the big-endian format for its random-access memory. This behavior does not seem to be modifiable.

Floating point[edit]

Although many processors use little-endian storage for all types of data (integer, floating point), there are a number of hardware architectures where floating-point numbers are represented in big-endian form while integers are represented in little-endian form.[26] There are ARM processors that have mixed-endian floating-point representation for double-precision numbers: each of the two 32-bit words is stored as little-endian, but the most significant word is stored first. VAX floating point stores little-endian 16-bit words in big-endian order. Because there have been many floating-point formats with no network standard representation for them, the XDR standard uses big-endian IEEE 754 as its representation. It may therefore appear strange that the widespread IEEE 754 floating-point standard does not specify endianness.[27] Theoretically, this means that even standard IEEE floating-point data written by one machine might not be readable by another. However, on modern standard computers (i.e., implementing IEEE 754), one may safely assume that the endianness is the same for floating-point numbers as for integers, making the conversion straightforward regardless of data type. Small embedded systems using special floating-point formats may be another matter, however.

Variable-length data[edit]

Most instructions considered so far contain the size (lengths) of their operands within the operation code. Frequently available operand lengths are 1, 2, 4, 8, or 16 bytes. But there are also architectures where the length of an operand may be held in a separate field of the instruction or with the operand itself, e.g. by means of a word mark. Such an approach allows operand lengths up to 256 bytes or larger. The data types of such operands are character strings or BCD. Machines able to manipulate such data with one instruction (e.g. compare, add) include the IBM 1401, 1410, 1620, System/360, System/370, ESA/390, and z/Architecture, all of them of type big-endian.

Simplified access to part of a field[edit]

On most systems, the address of a multi-byte value is the address of its first byte (the byte with the lowest address); little-endian systems of that type have the property that, for sufficiently low data values, the same value can be read from memory at different lengths without using different addresses (even when alignment restrictions are imposed). For example, a 32-bit memory location with content 4A 00 00 00 can be read at the same address as either 8-bit (value = 4A), 16-bit (004A), 24-bit (00004A), or 32-bit (0000004A), all of which retain the same numeric value. Although this little-endian property is rarely used directly by high-level programmers, it is occasionally employed by code optimizers as well as by assembly language programmers.[examples needed]

In more concrete terms, identities like this are the equivalent of the following C code returning true on most little-endian systems:

union { uint8_t u8; uint16_t u16; uint32_t u32; uint64_t u64; } u = { .u64 = 0x4A }; puts(u.u8 == u.u16 && u.u8 == u.u32 && u.u8 == u.u64 ? "true" : "false");

While not allowed by C++, such type punning code is allowed as «implementation-defined» by the C11 standard[28] and commonly used[29] in code interacting with hardware.[30]

On the other hand, in some situations it may be useful to obtain an approximation of a multi-byte or multi-word value by reading only its most significant portion instead of the complete representation; a big-endian processor may read such an approximation using the same base address that would be used for the full value.

Simplifications of this kind are of course not portable across systems of different endianness.

Calculation order[edit]

Some operations in positional number systems have a natural or preferred order in which the elementary steps are to be executed. This order may affect their performance on small-scale byte-addressable processors and microcontrollers. However, high-performance processors usually fetch multi-byte operands from memory in the same amount of time they would have fetched a single byte, so the complexity of the hardware is not affected by the byte ordering.

Addition, subtraction, and multiplication start at the least significant digit position and propagate the carry to the subsequent more significant position. On most systems, the address of a multi-byte value is the address of its first byte (the byte with the lowest address). The implementation of these operations is marginally simpler using little-endian machines where this first byte contains the least significant digit.

Comparison and division start at the most significant digit and propagate a possible carry to the subsequent less significant digits. For fixed-length numerical values (typically of length 1,2,4,8,16), the implementation of these operations is marginally simpler on big-endian machines.

Some big-endian processors (e.g. the IBM System/360 and its successors) contain hardware instructions for lexicographically comparing varying length character strings.

The normal data transport by an assignment statement is in principle independent of the endianness of the processor.

Middle-endian[edit]

Numerous other orderings, generically called middle-endian or mixed-endian, are possible.

The PDP-11 is in principle a 16-bit little-endian system. The instructions to convert between floating-point and integer values in the optional floating-point processor of the PDP-11/45, PDP-11/70, and in some later processors, stored 32-bit «double precision integer long» values with the 16-bit halves swapped from the expected little-endian order. The UNIX C compiler used the same format for 32-bit long integers. This ordering is known as PDP-endian.[31]

A way to interpret this endianness is that it stores a 32-bit integer as two little-endian 16-bit words, with a big-endian word ordering:

| increasing addresses → | |||||

| … | 0Bh | 0Ah | 0Dh | 0Ch | … |

| … | 0A0Bh | 0C0Dh | … |

The 16-bit values here refer to their numerical values, not their actual layout.

Segment descriptors of IA-32 and compatible processors keep a 32-bit base address of the segment stored in little-endian order, but in four nonconsecutive bytes, at relative positions 2, 3, 4 and 7 of the descriptor start.[32]

Endian dates[edit]

Dates can be represented with different endianness by the ordering of the year, month and day. For example, September 13, 2002 can be represented as:

- little-endian date (day, month, year), 13-09-2002

- middle-endian dates (month, day, year), 09-13-2002

- big-endian date (year, month, day), 2002-09-13 as with ISO 8601

In date and time notation in the United States, dates are middle-endian and differ from date formats worldwide.

Byte addressing[edit]

When memory bytes are printed sequentially from left to right (e.g. in a hex dump), little-endian representation of integers has the significance increasing from left to right. In other words, it appears backwards when visualized, which can be counter-intuitive.

This behavior arises, for example, in FourCC or similar techniques that involve packing characters into an integer, so that it becomes a sequences of specific characters in memory. Let’s define the notation 'John' as simply the result of writing the characters in hexadecimal ASCII and appending 0x to the front, and analogously for shorter sequences (a C multicharacter literal, in Unix/MacOS style):

' J o h n ' hex 4A 6F 68 6E ---------------- -> 0x4A6F686E

On big-endian machines, the value appears left-to-right, coinciding with the correct string order for reading the result:

| increasing addresses → | |||||

| … | 4Ah | 6Fh | 68h | 6Eh | … |

| … | ‘J’ | ‘o’ | ‘h’ | ‘n’ | … |

But on a little-endian machine, one would see:

| increasing addresses → | |||||

| … | 6Eh | 68h | 6Fh | 4Ah | … |

| … | ‘n’ | ‘h’ | ‘o’ | ‘J’ | … |

Middle-endian machines complicate this even further; for example, on the PDP-11, the 32-bit value is stored as two 16-bit words ‘Jo’ ‘hn’ in big-endian, with the characters in the 16-bit words being stored in little-endian:

| increasing addresses → | |||||

| … | 6Fh | 4Ah | 6Eh | 68h | … |

| … | ‘o’ | ‘J’ | ‘n’ | ‘h’ | … |

Byte swapping[edit]

Byte-swapping consists of rearranging bytes to change endianness. Many compilers provide built-ins that are likely to be compiled into native processor instructions (bswap/movbe), such as __builtin_bswap32. Software interfaces for swapping include:

- Standard network endianness functions (from/to BE, up to 32-bit).[33] Windows has a 64-bit extension in

winsock2.h. - BSD and Glibc

endian.hfunctions (from/to BE and LE, up to 64-bit).[34] - macOS

OSByteOrder.hmacros (from/to BE and LE, up to 64-bit).

Some CPU instruction sets provide native support for endian byte swapping, such as bswap[35] (x86 — 486 and later), and rev[36] (ARMv6 and later).

Some compilers have built-in facilities for byte swapping. For example, the Intel Fortran compiler supports the non-standard CONVERT specifier when opening a file, e.g.: OPEN(unit, CONVERT='BIG_ENDIAN',...). Other compilers have options for generating code that globally enables the conversion for all file IO operations. This permits the reuse of code on a system with the opposite endianness without code modification.

Logic design[edit]

Hardware description languages (HDLs) used to express digital logic often support arbitrary endianness, with arbitrary granularity. For example, in SystemVerilog, a word can be defined as little-endian or big-endian:

logic [31:0] little_endian; // bit 0 is the least significant bit logic [0:31] big_endian; // bit 31 is the least significant bit logic [0:3][7:0] mixed; // each byte is little-endian, but bytes are packed in big-endian order.

Files and filesystems[edit]

The recognition of endianness is important when reading a file or filesystem created on a computer with different endianness.

Fortran sequential unformatted files created with one endianness usually cannot be read on a system using the other endianness because Fortran usually implements a record (defined as the data written by a single Fortran statement) as data preceded and succeeded by count fields, which are integers equal to the number of bytes in the data. An attempt to read such a file using Fortran on a system of the other endianness results in a run-time error, because the count fields are incorrect.

Unicode text can optionally start with a byte order mark (BOM) to signal the endianness of the file or stream. Its code point is U+FEFF. In UTF-32 for example, a big-endian file should start with 00 00 FE FF; a little-endian should start with FF FE 00 00.

Application binary data formats, such as MATLAB .mat files, or the .bil data format, used in topography, are usually endianness-independent. This is achieved by storing the data always in one fixed endianness or carrying with the data a switch to indicate the endianness. An example of the former is the binary XLS file format that is portable between Windows and Mac systems and always little-endian, requiring the Mac application to swap the bytes on load and save when running on a big-endian Motorola 68K or PowerPC processor.[37]

TIFF image files are an example of the second strategy, whose header instructs the application about the endianness of their internal binary integers. If a file starts with the signature MM it means that integers are represented as big-endian, while II means little-endian. Those signatures need a single 16-bit word each, and they are palindromes, so they are endianness independent. I stands for Intel and M stands for Motorola. Intel CPUs are little-endian, while Motorola 680×0 CPUs are big-endian. This explicit signature allows a TIFF reader program to swap bytes if necessary when a given file was generated by a TIFF writer program running on a computer with a different endianness.

As a consequence of its original implementation on the Intel 8080 platform, the operating system-independent File Allocation Table (FAT) file system is defined with little-endian byte ordering, even on platforms using another endianness natively, necessitating byte-swap operations for maintaining the FAT on these platforms.

ZFS, which combines a filesystem and a logical volume manager, is known to provide adaptive endianness and to work with both big-endian and little-endian systems.[38]

Networking[edit]

Many IETF RFCs use the term network order, meaning the order of transmission for bits and bytes over the wire in network protocols. Among others, the historic RFC 1700 (also known as Internet standard STD 2) has defined the network order for protocols in the Internet protocol suite to be big-endian, hence the use of the term network byte order for big-endian byte order.[39]

However, not all protocols use big-endian byte order as the network order. The Server Message Block (SMB) protocol uses little-endian byte order. In CANopen, multi-byte parameters are always sent least significant byte first (little-endian). The same is true for Ethernet Powerlink.[40]

The Berkeley sockets API defines a set of functions to convert 16-bit and 32-bit integers to and from network byte order: the htons (host-to-network-short) and htonl (host-to-network-long) functions convert 16-bit and 32-bit values respectively from machine (host) to network order; the ntohs and ntohl functions convert from network to host order.[41][42] These functions may be a no-op on a big-endian system.

While the high-level network protocols usually consider the byte (mostly meant as octet) as their atomic unit, the lowest network protocols may deal with ordering of bits within a byte.

Bit endianness[edit]

Bit numbering is a concept similar to endianness, but on a level of bits, not bytes. Bit endianness[citation needed] or bit-level endianness refers to the transmission order of bits over a serial medium. The bit-level analogue of little-endian (least significant bit goes first) is used in RS-232, HDLC, Ethernet, and USB. Some protocols use the opposite ordering (e.g. Teletext, I2C, SMBus, PMBus, and SONET and SDH[43]), and ARINC 429 uses one ordering for its label field and the other ordering for the remainder of the frame. Usually, there exists a consistent view to the bits irrespective of their order in the byte, such that the latter becomes relevant only on a very low level. One exception is caused by the feature of some cyclic redundancy checks to detect all burst errors up to a known length, which would be spoiled if the bit order is different from the byte order on serial transmission.

Apart from serialization, the terms bit endianness and bit-level endianness are seldom used, as computer architectures where each individual bit has a unique address are rare. Individual bits or bit fields are accessed via their numerical value or, in high-level programming languages, assigned names, the effects of which, however, may be machine dependent or lack software portability.

Notes[edit]

- ^ An exception to this rule is e.g. the Add instruction of the IBM 1401 which addresses variable-length fields at their low-order (highest-addressed) position with their lengths being defined by a word mark set at their high-order (lowest-addressed) position. When an operation such as addition is performed, the processor begins at the low-order positions at the high addresses of the two fields and works its way down to the high-order.

- ^ If BCD-encoded, base 10 can be relevant for endianness.

- ^ Note that, in these expressions, the term «end» is meant as the extremity where the big resp. little significance is written first, namely where the field starts.

- ^ Almost all machines which can do this using one instruction only (see § Variable-length data) are anyhow of type big-endian or at least mixed-endian.

- ^ The PDP-11 architecture is little-endian within its native 16-bit words, but stores 32-bit data as an unusual big-endian word pairs.

References[edit]

- ^ Understanding big and little endian byte order

- ^ Byte Ordering PPC

- ^ Writing endian-independent code in C

- ^ «Internet Hall of Fame Pioneer». Internet Hall of Fame. The Internet Society.

- ^ Cary, David. «Endian FAQ». Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ James, David V. (June 1990). «Multiplexed buses: the endian wars continue». IEEE Micro. 10 (3): 9–21. doi:10.1109/40.56322. ISSN 0272-1732. S2CID 24291134.

- ^ Blanc, Bertrand; Maaraoui, Bob (December 2005). «Endianness or Where is Byte 0?» (PDF). Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- ^ RFC 1700. doi:10.17487/RFC1700.

- ^ Cohen, Danny (1980-04-01). On Holy Wars and a Plea for Peace. IETF. IEN 137.

…which bit should travel first, the bit from the little end of the word, or the bit from the big end of the word? The followers of the former approach are called the Little-Endians, and the followers of the latter are called the Big-Endians.

Also published at IEEE Computer, October 1981 issue. - ^ Swift, Jonathan (1726). «A Voyage to Lilliput, Chapter IV». Gulliver’s Travels.

- ^ Bryant, Randal E.; David, O’Hallaron (2016), Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective (3 ed.), Pearson Education, p. 79, ISBN 978-1-488-67207-1

- ^ «byte sex». www.catb.org. Retrieved 2022-12-16.

- ^ «about bytesex.org». linux.bytesex.org. Retrieved 2022-12-16.

- ^ «Byte Sex». CodeProject. 2014-03-29. Retrieved 2022-12-16.

- ^ A File Format for the Exchange of Images in the Internet. April 1992. p. 7. doi:10.17487/RFC1314. RFC 1314. Retrieved 2021-08-16.

TIFF files start with a file header which specifies the byte order used in the file (i.e., Big or Little Endian)

- ^ Tanenbaum, Andrew S.; Austin, Todd M. (4 August 2012). Structured Computer Organization. Prentice Hall PTR. ISBN 978-0-13-291652-3. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- ^ «NUXI problem». The Jargon File. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- ^ Jalics, Paul J.; Heines, Thomas S. (1 December 1983). «Transporting a portable operating system: UNIX to an IBM minicomputer». Communications of the ACM. 26 (12): 1066–1072. doi:10.1145/358476.358504. S2CID 15558835.

- ^ House, David; Faggin, Federico; Feeney, Hal; Gelbach, Ed; Hoff, Ted; Mazor, Stan; Smith, Hank (2006-09-21). «Oral History Panel on the Development and Promotion of the Intel 8008 Microprocessor» (PDF). Computer History Museum. p. b5. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

Mazor: And lastly, the original design for Datapoint … what they wanted was a [bit] serial machine. And if you think about a serial machine, you have to process all the addresses and data one-bit at a time, and the rational way to do that is: low-bit to high-bit because that’s the way that carry would propagate. So it means that [in] the jump instruction itself, the way the 14-bit address would be put in a serial machine is bit-backwards, as you look at it, because that’s the way you’d want to process it. Well, we were gonna built a byte-parallel machine, not bit-serial and our compromise (in the spirit of the customer and just for him), we put the bytes in backwards. We put the low-byte [first] and then the high-byte. This has since been dubbed «Little Endian» format and it’s sort of contrary to what you’d think would be natural. Well, we did it for Datapoint. As you’ll see, they never did use the [8008] chip and so it was in some sense «a mistake», but that [Little Endian format] has lived on to the 8080 and 8086 and [is] one of the marks of this family.

- ^ Lunde, Ken (13 January 2009). CJKV Information Processing. O’Reilly Media, Inc. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-596-51447-1. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ «Cx51 User’s Guide: E. Byte Ordering». keil.com.

- ^ Jeff Scheel (2016-06-16). «Little endian and Linux on IBM Power Systems». IBM. Retrieved 2022-03-27.

- ^ Timothy Prickett Morgan (10 June 2019). «The Transition To RHEL 8 Begins On Power Systems». ITJungle. ITJungle. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ «Differences between BE-32 and BE-8 buses».

- ^ «How to detect New Instruction support in the 4th generation Intel® Core™ processor family» (PDF). Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ Savard, John J. G. (2018) [2005], «Floating-Point Formats», quadibloc, archived from the original on 2018-07-03, retrieved 2018-07-16

- ^ «pack – convert a list into a binary representation».

- ^ «C11 standard». ISO. Section 6.5.2.3 «Structure and Union members», §3 and footnote 95. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

95) If the member used to read the contents of a union object is not the same as the member last used to store a value in the object, the appropriate part of the object representation of the value is reinterpreted as an object representation in the new type as described in 6.2.6 (a process sometimes called «type punning»).

- ^ «3.10 Options That Control Optimization: -fstrict-aliasing». GNU Compiler Collection (GCC). Free Software Foundation. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (5 Jun 2018). «[GIT PULL] Device properties framework update for v4.18-rc1». Linux Kernel (Mailing list). Retrieved 15 August 2018.

The fact is, using a union to do type punning is the traditional AND STANDARD way to do type punning in gcc. In fact, it is the *documented* way to do it for gcc, when you are a f*cking moron and use «-fstrict-aliasing» …

- ^ PDP-11/45 Processor Handbook (PDF). Digital Equipment Corporation. 1973. p. 165. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ AMD64 Architecture Programmer’s Manual Volume 2: System Programming (PDF) (Technical report). 2013. p. 80. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-02-18.

- ^

byteorder(3)– Linux Programmer’s Manual – Library Functions - ^

endian(3)– Linux Programmer’s Manual – Library Functions - ^ «Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual Volume 2 (2A, 2B & 2C): Instruction Set Reference, A-Z» (PDF). Intel. September 2016. p. 3–112. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- ^ «ARMv8-A Reference Manual». ARM Holdings.

- ^ «Microsoft Office Excel 97 — 2007 Binary File Format Specification (*.xls 97-2007 format)». Microsoft Corporation. 2007.

- ^ Matt Ahrens (2016). FreeBSD Kernel Internals: An Intensive Code Walkthrough. OpenZFS Documentation/Read Write Lecture.

- ^

Reynolds, J.; Postel, J. (October 1994). «Data Notations». Assigned Numbers. IETF. p. 3. doi:10.17487/RFC1700. STD 2. RFC 1700. Retrieved 2012-03-02. - ^ Ethernet POWERLINK Standardisation Group (2012), EPSG Working Draft Proposal 301: Ethernet POWERLINK Communication Profile Specification Version 1.1.4, chapter 6.1.1.

- ^

IEEE and The Open Group (2018). «3. System Interfaces». The Open Group Base Specifications Issue 7. Vol. 2. p. 1120. Retrieved 2021-04-09. - ^ «htonl(3) — Linux man page». linux.die.net. Retrieved 2021-04-09.

- ^ Cf. Sec. 2.1 Bit Transmission of draft-ietf-pppext-sonet-as-00 «Applicability Statement for PPP over SONET/SDH»

|

148 / 62 / 8 Регистрация: 14.12.2010 Сообщений: 347 Записей в блоге: 1 |

|

|

1 |

|

|

13.06.2013, 11:29. Показов 30971. Ответов 32

Всем привет! Народ подскажите мне пожалуйста простые прописные истины, а то я что то запутался! 0000 0000 0000 0101 — big-endian ?

1 |

|

Каратель 6606 / 4025 / 401 Регистрация: 26.03.2010 Сообщений: 9,273 Записей в блоге: 1 |

|

|

13.06.2013, 12:17 |

2 |

|

0000 0000 0000 0101 — little-endian

1 |

|

148 / 62 / 8 Регистрация: 14.12.2010 Сообщений: 347 Записей в блоге: 1 |

|

|

13.06.2013, 12:26 [ТС] |

3 |

|

Почему вы перевернули порядок бит в старшем байте в big-endian?

0 |

|

Каратель 6606 / 4025 / 401 Регистрация: 26.03.2010 Сообщений: 9,273 Записей в блоге: 1 |

|

|

13.06.2013, 12:31 |

4 |

|

stawerfar, при чем тут порядок бит? разница между little-endian и big-endian в порядке байт

3 |

|

148 / 62 / 8 Регистрация: 14.12.2010 Сообщений: 347 Записей в блоге: 1 |

|

|

13.06.2013, 12:39 [ТС] |

5 |

|

А еще было бы не плохо если бы вы меня сослали на нормальный источник что бы я мог вас не мучитьь глупыми вопросами Добавлено через 2 минуты

1 |

|

2375 / 1659 / 279 Регистрация: 29.05.2011 Сообщений: 3,387 |

|

|

13.06.2013, 12:47 |

7 |

|

Решение Позволю-ка я себе не согласиться с Jupiter. В исходном сообщении правильный порядок (только непонятно, зачем байты разделены по 4 бита).

6 |

|

stawerfar 148 / 62 / 8 Регистрация: 14.12.2010 Сообщений: 347 Записей в блоге: 1 |

||||

|

13.06.2013, 12:52 [ТС] |

8 |

|||

|

Да понятно спасибо. А пробелы поставил для удобства чтения.

0 |

|

2375 / 1659 / 279 Регистрация: 29.05.2011 Сообщений: 3,387 |

|

|

13.06.2013, 12:55 |

9 |

|

тогда скажите мне как приходит усечение из 2-х байт в 1 байт. А где здесь усечение? Проверяется байт по младшему адресу в записи числа 1. В big-endian там будет 0, в little-endian — единица.

1 |

|

Каратель 6606 / 4025 / 401 Регистрация: 26.03.2010 Сообщений: 9,273 Записей в блоге: 1 |

|

|

13.06.2013, 13:03 |

10 |

|

в порядке увеличения адресов сначала располагается старшая часть числа, затем младшая: верно, только у Вас слева на право увеличение адресов, а у меня наоборот, хотя с big-endian я накосячил:

непонятно, зачем байты разделены по 4 бита

1 |

|

148 / 62 / 8 Регистрация: 14.12.2010 Сообщений: 347 Записей в блоге: 1 |

|

|

13.06.2013, 13:07 [ТС] |

11 |

|

Спасибо теперь я все понял

0 |

|

4202 / 1794 / 211 Регистрация: 24.11.2009 Сообщений: 27,562 |

|

|

13.06.2013, 14:12 |

12 |

|

Почему вы перевернули порядок бит в старшем байте в big-endian? Он перевернул порядок полубайт, а не порядок бит. Если бы бит, то 1010 0000 0000 0000. Обсчитался, в итоге попутал байты с полубайтами.

1 |

|

stawerfar 148 / 62 / 8 Регистрация: 14.12.2010 Сообщений: 347 Записей в блоге: 1 |

||||

|

14.06.2013, 14:04 [ТС] |

13 |

|||

|

С направлением байт вроде разобрался и естественно хотел посмотреть на это на примере.

0 |

|

148 / 62 / 8 Регистрация: 14.12.2010 Сообщений: 347 Записей в блоге: 1 |

|

|

14.06.2013, 14:13 [ТС] |

14 |

|

Вот консольный вывод Миниатюры

0 |

|

Убежденный Ушел с форума 16454 / 7418 / 1186 Регистрация: 02.05.2013 Сообщений: 11,617 Записей в блоге: 1 |

||||

|

14.06.2013, 17:44 |

15 |

|||

|

Зачем так сложно ?

>cdab3412 Добавлено через 3 минуты

template <typename type> Что делает эта функция ? Из названия непонятно.

int sizebyte = sizeof(val); Этот фрагмент определяет лишь то, как относительно друг друга расположены

1 |

|

148 / 62 / 8 Регистрация: 14.12.2010 Сообщений: 347 Записей в блоге: 1 |

|

|

14.06.2013, 22:00 [ТС] |

16 |

|

Компилятор может расположить их в памяти так, Про какой барьер компилятора вы говорите? И как его применять? Добавлено через 11 минут

#include <iostream> То что вы написали это шестнадцатиричный вид значений каждого байта. Да не спорю по результату видно что байты перевернуты. Но я в примерах смотрю на числа через битовую маску, тем самым могу увидеть бинарное представление числа.

0 |

|

2375 / 1659 / 279 Регистрация: 29.05.2011 Сообщений: 3,387 |

|

|

14.06.2013, 22:08 |

17 |

|

В первом случае в функции trigerbyte я не преобразую переменную (которую нужно посмотреть в бинарном виде) к указателю на тип и получаю в результате вид числа (например) 5 таким 0000 0000 0000 0101(значение в short) В этом случае компилятор следит, чтобы младший бит оказался «самым правым», а страший — «самым левым». То есть когда мы говорим про младший разряд или байт какого-то числа или пременной, то это забота компилятора, чтобы они оказались именно младшими. От машинного представления числа это не зависит, мы не спускаемся до машинного представления.

я не преобразую переменную (которую нужно посмотреть в бинарном виде) к указателю на тип Ну а вот когда преобразуешь — сам спускаешься до понятий байт и бит, которых для чисел и переменных с точки зрения языка нет. Значит должен сам учитывать машинное представление. Теперь от него порядок байт зависит напрямую.

1 |

|

148 / 62 / 8 Регистрация: 14.12.2010 Сообщений: 347 Записей в блоге: 1 |

|

|

14.06.2013, 22:24 [ТС] |

18 |

|

Спасибо! Добавлено через 1 минуту

0 |

|

2375 / 1659 / 279 Регистрация: 29.05.2011 Сообщений: 3,387 |

|

|

14.06.2013, 22:27 |

19 |

|

Про барьеры не знаю, но выражение (&sizebyte < &sizebit) действительно бессмысленное.

1 |

|

stawerfar 148 / 62 / 8 Регистрация: 14.12.2010 Сообщений: 347 Записей в блоге: 1 |

||||

|

14.06.2013, 22:41 [ТС] |

20 |

|||

|

Да я согласен нужно было использовать например

Добавлено через 1 минуту

0 |

Endianness describes the byte order in which bytes of large values are stored, transferred and accessed. Based on order in which bytes are stored, transmitted and accessed there are two main types of endianness called little-endian and big-endian .

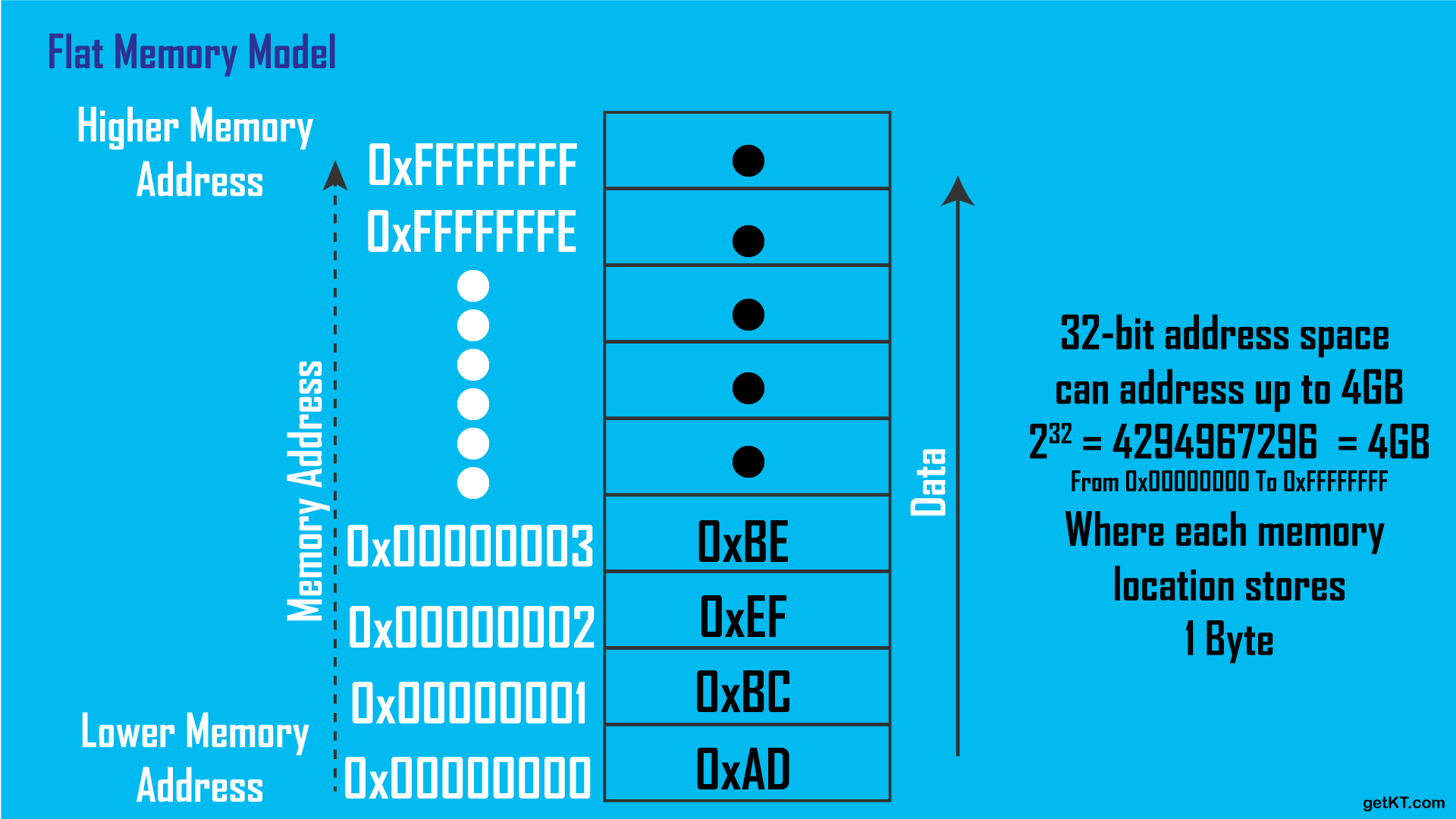

Before we understand Little Endian and Big Endian we need to understand how memory and it’s addressing work.

Computer Memory Address

Computer memory is generally abstracted as an ordered series of bytes. Memory address is a number which is reference to a specific memory location in which data(by bytes) is stored . Where computer divides memory into bytes, each byte is assigned a unique number which is a memory address so called byte addressable. Whole memory (like RAM) is addressed by bytes regardless of whether it is being used or not for storage. So that CPU can track where data and instructions are stored in RAM by using memory address.

First memory location(byte) is assigned lowest possible memory address and further locations are addressed with increasing memory address. Large values are divided into bytes and placed in each memory location.

Question: How large values that require more than one byte to store or transmit are arranged ?

Order in which bytes of large values are stored or transmitted over network is described by Endianness or Byte Order .

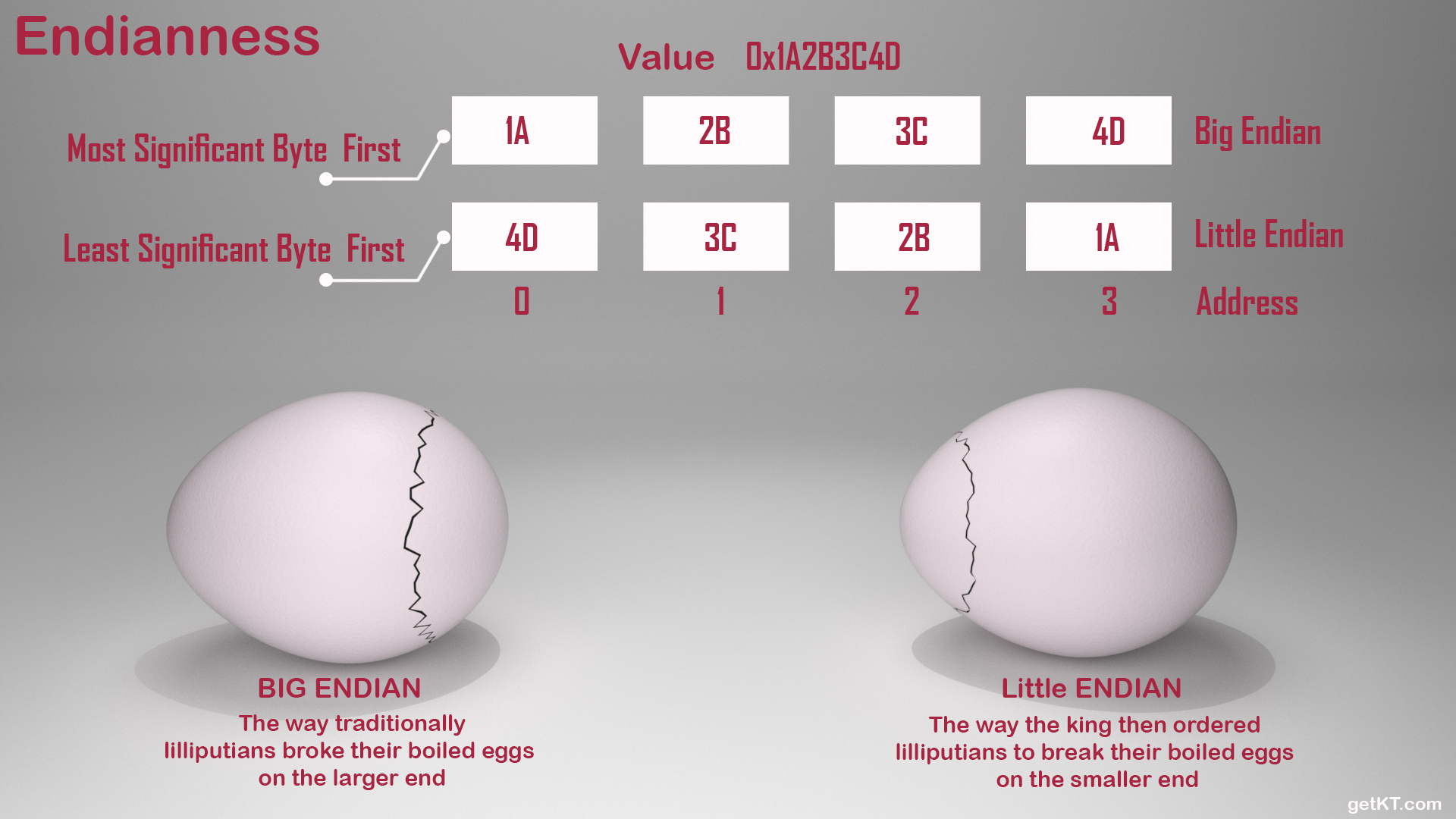

To better understand byte order. Have a look at terminology Least Significant Byte, Most Significant Byte, Left Most Byte and Right Most Byte.

In any positional number system including binary we count position from right to left. As we write numbers(from left to write) in binary representation of decimal number we call,

- Byte which is having least positional value is called Least Significant Byte

- Least Significant Byte can also be called as Right Most Byte since it comes right most as we write from left to right

- Byte which is having greatest positional value is called Most Significant Byte

- Most Significant Byte can also be called as Left Most Byte since it comes left most as write from left to right

Following Image illustrates terms Least Significant Byte and Most Significant Byte. By taking number 0x1A2B3C4D which is of size 32 bits.

Least significant byte can also be referred as LSB or LSByte

Most significant byte can also be referred as MSB or MSByte

The Origin Of Words Of Endianness

Words Little Endian and Big Endian are originated from the 1726 novel Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift. In which civil war breaks out over whether the big end or the little end of the egg is proper to crack open. Words Little Endian and Big Endian are used to name two groups who fight over little end and big end of the egg is proper way to break egg receptively .

The novel further describes an intra-Lilliputian quarrel over the practice of breaking eggs. Traditionally, Lilliputians broke boiled eggs on the larger end; a few generations ago, an Emperor of Lilliput, the Present Emperor’s great-grandfather, had decreed that all eggs be broken on the smaller end after his son cut himself breaking the egg on the larger end. The differences between Big-Endians (those who broke their eggs at the larger end) and Little-Endians had given rise to “six rebellions… wherein one Emperor lost his life, and another his crown”. The Lilliputian religion says an egg should be broken on the convenient end, which is now interpreted by the Lilliputians as the smaller end. The Big-Endians gained favour in Blefuscu.

Excerpt of story from wiki Lilliput and Blefuscu

Endianness. The Byte Order

Endianness is also called as Byte Order which describes order in which bytes of large values are stored in memory or transmitted over network in a transmission protocol or a stream (ex. an audio, video streams).

There are two main endianness formats based on whether Most Significant Byte (MSB) or Least Significant Byte (LSB) comes first, when storing data or transmitting streams. Which are Little-Endian and Big-Endian

- If Least Significant Byte (LSB) is stored or transmitted first, it is said to be Little-Endian

- If Most Significant Byte (MSB) is stored or transmitted first, it is said to be Big-Endian

Using words Little-Endian and Big-Endian for byte order is analogous to cracking egg on little end and big end respectively

It is interesting topic in computer science, since these two formats are conflicting. Using wrong byte order may potentially read wrong data or corrupt when writing.

Most Computers prefer to handle all of it’s data in single byte order. Systems native byte order is default

You may not need to worry about endianness and endianness conversion unless you work with assembly, drivers, middle level languages like c, embedded systems and low level networking transports. High level programming languages will take care of it for you.

Little Endian

Like Little-Endians crack egg on little end, least significant byte is stored or transmitted over network first in Little-Endian format. Little endian format is also called as host byte order.

Little-Endian is also known as the “Intel convention”. As Intel used little-endian format from it’s earlier processors.

- Least significant byte is stored or transmitted first

- When bytes of large values are stored in memory “Least Significant Byte” is placed first in memory at lowest memory address

- Numeric significance or positional value is increased with increasing memory address

- Easier mathematical computation. Mathematical operations mostly work from LSB

Big Endian

Like Big-Endians crack egg on big end, most significant byte is stored or transmitted over network first in Big-Endian format. Big endian format is also called as network byte order.

Over decades most of processors took transition to little endian at present many processors(laptops, desktops and servers) come in little endian. Yet, big endian is widely used for network transmission. So it is called “network byte order” .

Big-Endian is also known as the “Motorola convention”.Back then as it was widely used by Motorola processors.

- Most significant byte is stored or transmitted first

- When bytes of large values are stored in memory “Most Significant Byte” is placed first in memory at lowest memory address

- Numeric significance or positional value is decreased with increasing memory address

- Quick sign checking. Since MSB stores first.

- Better human readability as it is one to one mapping. Bytes are in the same order as we write.

Check Native Endianness (Native Byte Order)

Check native “byte order” of system using linux command line (terminal)

You can use the command “lscpu” to get CPU information including it’s byte order

# lscpu

Architecture: x86_64

CPU op-mode(s): 32-bit, 64-bit

Byte Order: Little Endian

CPU(s): 2

On-line CPU(s) list: 0,1

Thread(s) per core: 1

Core(s) per socket: 2

Socket(s): 1

NUMA node(s): 1

Vendor ID: GenuineIntel

CPU family: 6

Model: 158

Model name: Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-7700HQ CPU @ 2.80GHz

Stepping: 9

CPU MHz: 2808.002

BogoMIPS: 5616.00

Hypervisor vendor: KVM

Virtualization type: full

L1d cache: 32K

L1i cache: 32K

L2 cache: 256K

L3 cache: 6144K

NUMA node0 CPU(s): 0,1

Flags: fpu vme de pse tsc msr pae mce cx8 apic sep mtrr pge mca cmov pat pse36 clflush mmx fxsr sse sse2 ht syscall nx rdtscp lm constant_tsc rep_good nopl xtopology nonstop_tsc cpuid pni pclmulqdq ssse3 cx16 pcid sse4_1 sse4_2 x2apic movbe popcnt aes xsave avx rdrand hypervisor lahf_lm abm 3dnowprefetch invpcid_single pti fsgsbase avx2 invpcid rdseed clflushopt

As you can see endianness(byte order) in the above output “Byte Order: Little Endian“.

Check native byte order using python programming language

Python sys module has attribute called “byteorder” where it’s value describes native byte order of the system .

- sys.byteorder will be “big” if it’s big-endian (most significant byte first) platform

- sys.byteorder will be “little” if it is little-endian (least significant byte first) platform

>>> import sys

>>> sys.byteorder

little

Check native byte order of system using java

In java “java.nio.ByteOrder” provides flags “BIG_ENDIAN” and “LITTLE_ENDIAN” to denote Big-Endian and Little-Endian respectively. It has the static method “nativeOrder()” to get system’s native byte order.

java.nio.ByteOrder.nativeOrder()

Check endianness of system using C program

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

unsigned int i = 1;

char *c = (char*)&i;

if (*c)

printf("Little Endian System");

else

printf("Big Endian System");

getchar();

return 0;

}

Above c program prints Endianess of the system. In the above program we have used character pointer “c” to dereference integer “i“. Since size of character is 1 byte it will contain only first byte of integer.

- *c will return 1 which is Least Significant Byte on Little-Endian machine.

- *c will return 0 which is Most Significant Byte on Big-Endian machine

Print memory representation of multibyte data

Following “c” program prints memory representation of given 32-bit integer. You can see byte order in action, order in which given 32-bit integer is stored in memory either by Little-Endian or Big-Endian.

Above program will print ” 4d 3c 2b 1a” if machine is Little-Endian (Least Significant Byte Fist) or “1a 2b 3c 4d” if machien is Big-Endian (Most Significant Byte Fist)

Convert Endianness

It is required sometimes to convert endianness. You don’t have to worry about converting endiannes if you are working application level. For data exchange between machines common format is used. Yet if machine is little endian often data sent over network is big endian. Big-Endian is standard byte order for network communication. In such a case we have to convert data that we receive in Big-Endian to host fomat little endian and when we send data back to network need to convert Little-Endian to Big-Endian. There are many utility function to perform this conversion.

Following function are available in c to help endianness conversion

htons() – Host to Network Short

htonl() – Host to Network Long

ntohs() – Network to Host Short

ntohl() – Network to Host Long

Python library NumPy provides way to convert endianness. NumPy library uses c types and low level data structures behind.

How Systems Of Different Endianness Interact

Files that are created on little-endian machine won’t be read as they were created on big-endian machines without conversion. This is the reason, some programs binary file formats which are endianness independent. Where files are endianness dependent byte order marks are used in headers of file to hint a program endianness of the file.

Example: TIFF files use MM and II in header (begning of file) for big-endian and little-endian respectively. Where MM and II are palindromes these are endianness independent, interpreted same on both little-endian and big-endian machines.

Unicode uses byte order mark in the beginning of the stream to indicated endianness of following unicode bytes.

Endianness problems. Who needs to worry about byte order

You don’t need to worry much if you work with application layer protocols or high level programming languages, but it is good to know.

Think what’s the out put of following program

#include <stdio.h>void foo(void *d){

printf("Data = %dn", *(char *)d);

}int main(void){

unsigned int i = 1;

foo(&i);

}

Summary

- Words Little-Endian and Big-Endian came from 1726 novel Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift

- System is said to be Little-Endian if it stores or transmits Least Significant Byte First

- System is said to be Big-Endian if it stores or transmits Most Significant Byte First

- Command “lscpu” on linux will print CPU information including Byte Order (Endianness)

- Currently most of processors are base on little endian

- Big Endian is mostly used in network protocols so called network byte order .

- You don’t have to worry about byte order (endianness) compatibility, system will take care of it behind the senses. Unless you work with assembly, c/c++ language, drivers, embedded system and low level network transports.

- Choose One endianness and stick to it to avoid obscured bugs.

If you need to read binary files or binary streams, you need to know whether the file you’re reading is big-endian or little-endian.

It’s about the order that the bytes are stored in the file. For example the number 1, stored as a 32 bit integer, is 00000001, occupying 4 bytes. That means you need a sequence of four bytes in the file to store the number. If you put the byte that holds the most significant bits first, then the bytes look like this:

The official term for that is big-endian. On the other hand, if you put the least significant byte first in the file, then the bytes look like this:

That’s known in the trade as little-endian. Obviously, if you are writing code to read a binary file, you’d better make sure you know which convention is being used in the file because if your program tries to read the bytes the wrong way round, it’ll probably read the number 1 as if it was hex 01000000 which works out at about 16 million (16 777 216). If the number being read is the number of bugs assigned to your intern to fix before lunchtime today, and your (perfectly healthy) intern suddenly dies of a heart attack then – well, don’t say I didn’t warn you that you need to check the endian-ness!

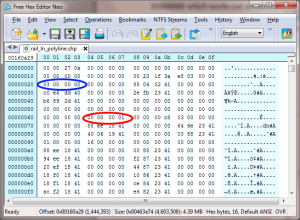

As it happens I’m currently working with binary files. This is one of the files that the app I’m working on needs to read – viewed using the free Hex Editor Neo from HHD.

Each byte of the file is displayed as a 2-digit hex number, so the first two bytes in the file both contain zero, the third byte contains the value 0x27, the fourth byte contains the value 0x0a, and so on.

(If you must know, the file is an ESRI shape file that contains geographical data about UK railway lines, And the Hex Editor Neo is very good by the way. I highly recommend it if you want to view binary files).But back to the point, look at the four bytes I’ve circled in red. That is actually the number 1, stored in 32-bit big-endian format. On the other hand, the number I’ve circled in blue is actually the number 3, stored in 32-bit little-endian format – with the least significant byte first. What, both formats mixed up in the same file? Yep, sometimes, stuff in computing is just weird. Don’t blame me – I didn’t write the ESRI shape file format, I just have to read the darn thing.

Personally I like big-endian because it’s easy for a human to read. With little-endian you have to mentally reverse the order of the bytes to see what number it is, but with big-endian you don’t have to do that. That’s because we always write numbers in big-endian on paper. In the number 73, the 7 is the most significant digit, and it comes first.

By the way, which convention do you think Windows usually uses? Yep, you got it, Windows normally uses little-endian. Just to make things difficult for humans. Actually, it’s not really Microsoft being awkward – there are good historical reasons for this choice, that are to do with (roughly speaking) little endian being slightly simpler to build hardware for a very long time ago when hardware was expensive. And the result is that normally, the hardware that Windows runs on is itself little-endian. But that’s getting way off topic for what I want to talk about.

So let’s recap:

- Little-endian means that the least significant bits come first. It’s what you’ll normally find Windows uses by default.

- Big-endian means that the most significant bits come first.

So the concept is quite simple. I doubt anyone has any trouble understanding the idea. Where the trouble comes is in trying to remember which is which.

And the terminology really doesn’t help here. Arguably, both the words big-endian and little-endian actually mean the opposite of what you’d logically think if break the words down. The word big-endian makes it sound like the big (ie. most significant) bits come at the end (ie. last). But it’s the opposite – big-endian means the big bits come first.

Similarly little-endian means that the little (least significant) bits come first, even though it sounds like it they should come last.

It would really make a lot more sense if the conventions were called big-first and little-first. But they aren’t and it sucks and there’s not much you or I can do about it.

And that’s my mnemonic to remember the convention with: I just remind myself that lots of things in programming are warped, strange, and counterintuitive, and big-endian/little-endian follows that pattern perfectly.

Sorted?

Actually not yet. We still need a way to remember that the Windows world generally tends to use little-endian. In fact the idea of little-endian is so strongly embedded in Windows that several of the .NET stream classes are out of the box only capable of reading little-endian data. And that is oh so very useful when you have to write code to read – say, to pick a random example – an ESRI shape file that contains big-endian data. But I digress, that’s for the next TechieSimon article.

Let’s get back on topic and think: How you remember that MS is little-endian?

My solution is: Just remember (again) that stuff in programming is warped and counter-intuitive. From the point of view of a human being, little-endian makes no sense whatsoever, because it’s the opposite of how you normally read numbers. But if you remember that everything is warped in programming then you’re fine. (Note: This works if you’re doing Windows desktop programming. Obviously, it’s not going to help you if you’re working on some other architecture that does in fact use big-endian).

So, there we have it. Little-endian = Little bits first because the terminology is warped. MS uses little-endian which is hard to read, because computing is warped. Simple, huh!

But, having figured out to remember it, how do I really cement that in my brain?

Hmmmm…

Ah! Got it! In my experience, you understand things better after you’ve explained them to other people. So… I’ll write a blog about it! The act of writing a few witty put-downs about endian-ness should seal the knowledge deep in my brain, never to be forgotten.

And I hereby apologize that I have now written the blog. You’ve almost finished reading it, in fact. That means the blog is done and is publically available for anyone to read, so there is no reason at all for you to write one. That means you’ll never be able to remember which way round is little-endian without looking it up. Hah! Maybe it’s time for you to bookmark the techiesimon link that’s currently sitting in your browser’s address bar just above these words. Nah!

Next time: How to read big-endian in .NET. Extension methods to the rescue.

Добавлено 11 июня 2019 в 04:47

Различные термины «порядка байтов» («endian») могут показаться немного странными, но основная концепция довольно проста. Если вы еще не хорошо знакомы с вариантами порядка байтов, читайте статью дальше!

Порядок байтов, прямой порядок (big endian), обратный порядок (little endian). Что означают эти термины, и как они влияют на работу инженеров?

Что такое порядок байтов?

Оказывает, это неправильный вопрос. При обсуждении данных «порядок байтов» не является отдельным термином. Вернее, к форматам расположения байтов относятся термины «прямой порядок» («big-endian») и «обратный порядок» («little-endian»).

Термины берут начало в «Путешествиях Гулливера» Джонатана Свифта, в которых начинается гражданская война между теми, кто предпочитает разбивать вареные яйца на большом конце («big-endians»), и теми, кто предпочитает разбивать их на маленьком конце («little-endians»).

В 1980 году израильский ученый-компьютерщик Денни Коэн написал статью («О священных войнах и призыве к миру»), в которой он представил насмешливое объяснение столь же мелкой «войны», вызванной одним вопросом:

«Каков правильный порядок байтов в сообщениях?»

Чтобы объяснить эту проблему, он позаимствовал у Свифта термины «big endian» и «little endian», чтобы описать две противоположные стороны дискуссии о том, что он называл «endianness» (в данном контексте «порядок байтов»).

Когда Свифт писал «Путешествия Гулливера» где-то в первой четверти восемнадцатого века, он, конечно, не знал, что однажды его работа послужит вдохновением для неологизмов двадцатого века, которые определяют расположение цифровых данных в памяти и системах связи. Но такова жизнь – часто странная и всегда непредсказуемая.

Зачем нам нужен порядок байтов

Несмотря на сатирическую трактовку Коэном борьбы «big endians» (прямого порядка, от старшего к младшему) против «little endians» (обратного порядка, от младшего к старшему), вопрос о порядке байтов на самом деле очень важен для нашей работы с данными.

Блок цифровой информации – это последовательность единиц и нулей. Эти единицы и нули начинаются с наименьшего значащего бита (least significant bit, LSb – обратите на строчную букву «b») и заканчиваются на наибольшем значащем бите (most significant bit, MSb).

Это кажется достаточно простым; рассмотрим следующий гипотетический сценарий.

32-разрядный процессор готов к сохранению данных и, следовательно, передает 32 бита данных в соответствующие 32 блока памяти. Этим 32 блокам памяти совместно назначается адрес, скажем 0x01. Шина данных в системе спроектирована таким образом, что нет возможности смешивать LSb с MSb, и все операции используют 32-битные данные, даже если соответствующие числа могут быть легко представлены в 16 или даже 8 битами. Когда процессору требуется получить доступ к сохраненным данным, он просто считывает 32 бита с адреса памяти 0x01. Эта система является надежной, и нет необходимости вводить понятие порядка байтов.

Возможно, вы заметили, что слово «байт» в описании этого гипотетического процессора нигде не упоминалось. Всё основано на 32-битных данных – зачем нужно делить эти данные на 8-битные части, если всё оборудование предназначено для обработки 32-битных данных? Вот здесь-то теория и реальность расходятся. Реальные цифровые системы, даже те, которые могут напрямую обрабатывать 32-битные или 64-битные данные, широко использую 8-битный сегмент данных, известный как байт.

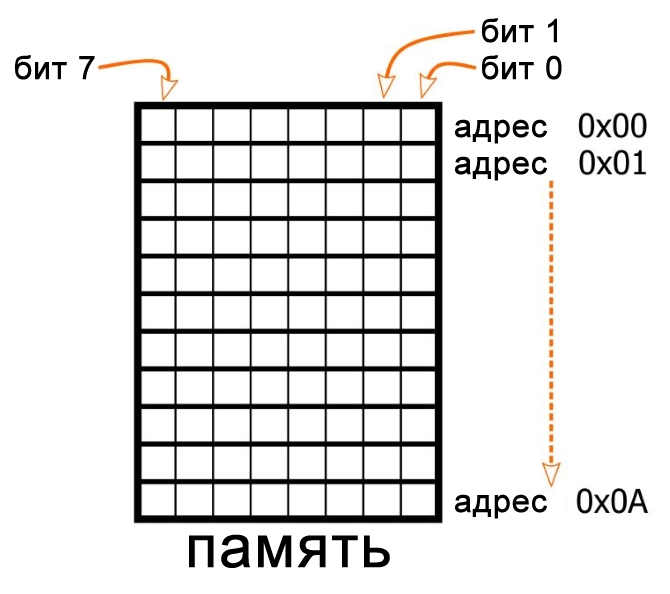

Порядок байтов в памяти

Удобным средством демонстрации порядка байтов действии и объяснения разницы между прямым и обратным порядками является процесс хранения цифровых данных. Представьте, что мы используем 8-разрядный микроконтроллер. Всё аппаратное обеспечение в этом устройстве, включая ячейки памяти, предназначено для 8-битных данных. Таким образом, адрес 0x00 может хранить один байт, адрес 0x01 тоже хранит один байт, и так далее.

Допустим, мы решили запрограммировать этот микроконтроллер, используя компилятор C, который позволяет нам определять 32-разрядные (т.е. 4-байтовые) переменные. Компилятор должен хранить эти переменные в смежных ячейках памяти, но что не очень понятно, так это то, в самом младшем адресе памяти должен храниться наибольший значащий байт (most significant byte, MSB – обратите внимание на заглавную «B») или наименьший значащий байт (least significant byte, LSB).

Другими словами, должна ли система использовать порядок памяти от старшего к младшему (прямой порядок, big-endian) или от младшего к старшему (обратный порядок, little-endian)?

Здесь на самом деле нет правильного или неправильного ответа – любая договоренность может быть совершенно эффективной. Решение между прямым и обратным порядком может быть основано, например, на поддержании совместимости с предыдущими версиями данного процессора, что, конечно, поднимает вопрос о том, как инженеры приняли решение для первого процессора в этом семействе. Я не знаю; возможно, генеральный директор подбросил монету.

Прямой порядок против обратного порядка

Прямой порядок (big endian) указывает на организацию цифровых данных, которая начинается с «большого» конца слова данных и продолжается в направлении «маленького» конца, где «большой» и «маленький» соответствуют наибольшему значащему и наименьшему значащему битам соответственно.

Обратный порядок (little endian) указывает на организацию, которая начинается с «маленького» конца и продолжается в направлении «большого» конца.

Решение между прямым и обратным порядками байтов не ограничивается схемами памяти и 8-разрядными процессорами. Байт является универсальной единицей в цифровых системах. Подумайте только о персональных компьютерах: пространство на жестком диске измеряется в байтах, ОЗУ измеряется в байтах, скорость передачи данных по USB указывается в байтах в секунду (или в битах в секунду), и это несмотря на тот факт, что 8-разрядные персональные компьютеры полностью устарели. Вопрос о порядке байтов вступает в игру всякий раз, когда цифровая система совмещает хранение или передачу данных на основе байтов с числовыми значениями, длина которых превышает 8 бит.

Инженеры должны знать о порядке байтов, когда данные хранятся, передаются или интерпретируются. Последовательная связь особенно восприимчива к проблемам с порядком байтов, поскольку байты, содержащиеся в многобайтовом слове данных, неизбежно будут передаваться последовательно, обычно либо от MSB до LSB, либо от LSB до MSB.

Параллельные шины не защищены от путаницы с порядком байтов, поскольку ширина шины может быть короче ширины данных. И в этом случае прямой или обратный порядок байтов должен быть выбран для параллельной побайтовой передачи данных.

Примером интерпретации на основе порядка байтов является случай, когда байты данных передаются от модуля датчика на ПК через «последовательный порт» (что в настоящее время почти наверняка означает, что в качестве COM порта используется USB соединение). Допустим, всё, что вам нужно сделать, это вывести эти данные, используя какой-то код MATLAB. Когда вы вводите эти байты в среду MATLAB и конвертируете их в обычные переменные, вы должны интерпретировать значения отдельных байтов в соответствии с порядком, в котором они хранятся в памяти.

Заключение

Очень жаль, что универсальная система порядка байтов не была создана еще в начале цифровой эпохи. Я даже не хочу знать, сколько коллективных часов человеческой жизни было посвящено решению проблем, вызванных несовпадающим порядком байтов.

В любом случае, мы не можем изменить прошлое, и мы также вряд ли убедим каждую компанию, производящую полупроводниковую технику и программное обеспечение, пересмотреть свои производственные линии для достижения единого универсального порядка байтов. Что мы можем сделать, так это добиваться согласованности наших собственных проектов и предоставлять четкую документацию, если существует вероятность конфликта между двумя составляющими частями системы.

Теги

Big EndianLittle EndianМикропроцессорПамятьПорядок байтовПоследовательная связь

Сообщение было отмечено как решение

Сообщение было отмечено как решение